Interim Report

The Project

How did law emerge in the modern period beyond the big codes (e.g. the civil code, the commercial code), or even outside of state law? Which special legal orders were created alongside the “general” law? It has long been understood that the economy institutes its own law—through company terms and conditions, cartel agreements, collective bargaining contracts, technical standards, etc. We thus recognize the existence of non-state law, but we know very little about its contents and, consequently, the effects it had: To what extent has it determined the spheres of economy and labor with inhibitory or innovative effects? How has its relationship to state law developed? Did non-state law supplement statutory law or did it undermine it? What scope of application did it develop? What quality level of legal technique did it reach?

These questions attain special prominence in labor law. When looking at the issues of non-state law, labor law provides an excellent field of reference—above all, because legislators there refrained from regulating important matters for a long time. Even though there were legal provisions, e.g. in the Prussian General Land Law (Preußisches Allgemeines Landrecht), in the Industrial Code (Gewerbeordnung), and in the German Civil Code (BGB), the applicable law in employer-employee relations was for a long time predominantly regulated by work regulations of the companies (Arbeitsordnungen) and then increasingly in collective bargaining agreements. In addition, there were other types of regulations in which the socio-political aspects of the employment relationship and issues of collective labor law were regulated, e.g. regulations for company health insurance funds, occupational health and safety requirements, codes of conduct for workers’ councils, strike insurance regulations, rules of employers’ and employees’ associations, etc.

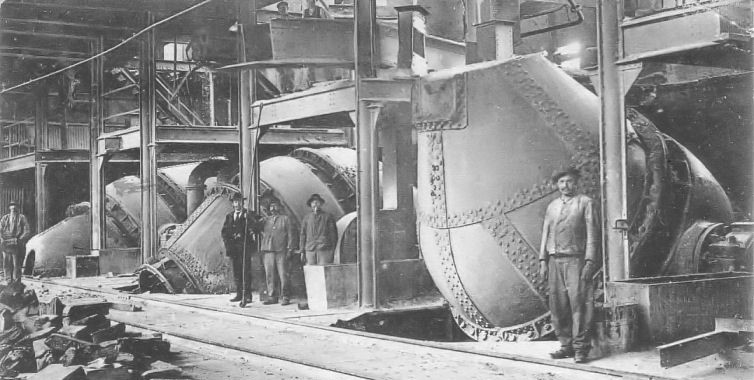

In the project “Non-state Law of the Economy. The normative order of industrial relations in the metal industry from the Empire to the early years of the Federal Republic of Germany,” this diversity of labor law norms is studied and presented in digital form. The search concentrates on the industrial sector that long played a leading role in Germany: the metal industry. The period under investigation covers the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. The regions examined are Saxony, Berlin, and individual locations in the Westphalian industrial area and in southern Germany.

The project began at the end of 2019 with a duration of five years. It is supported by the Hans Böckler Foundation, the Association of the Metal and Electric Industry North Rhine-Westphalia (Metall NRW), and the German Economic Institute, IW Medien (Cologne).

The Project Team

Research and Investigation

Three scholars work under the direction of Peter Collin. They travel to the archives, examine sources and make copies as templates to be digitalized. Their own projects are closely linked to this: Johanna Wolf’s habilitation project focuses on the history of work regulations (Arbeitsordnungen), Matthias Ebbertz is investigating the normative structures of internal company power relations for his dissertation project, and Tim-Niklas Vesper is writing a dissertation on the history of company welfare policy.

Digital Humanities – Conceptual planning, Coordination, and TEI-XML-Formatting

The project is supported by colleagues in the institute’s department for digital humanities. Andreas Wagner devises and models the project’s digital architecture, while Polina Solonets is responsible for the conversion of source materials to the TEI-XML format (see below).

Digital Humanities – OCR Procedures and Other Supportive Tasks

We have three additional student assistants on the project: Lisa Michel, Ben Gödde, and Annika Walther. They primarily take care of the conversion of sources from image files to text data (through our OCR procedure, see below).

The Sources

Countless sources are available which shed light on the research questions outlined above. To clarify this scope—from 1892 on, any company with more than 20 workers was obliged to issue work regulations. This abundance of data lends itself to the creation of a digital corpus of sources that reveals the non-state law of the metal industry in all its diversity and interconnectedness.

On the other hand, these sources are delivered through a variety of media formats (government files, company files, separate publications, newspaper issues) and are spread across a multitude of local, regional and central public archives, private archives, and libraries. This complicates the situation and makes research and indexing time-consuming. So far, sources have been collected from the following archives and libraries:

| Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv München |

| Bayerisches Wirtschaftsarchiv München |

| Berlin-Brandenburgisches Wirtschaftsarchiv Bibliothek der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung |

| Bundesarchiv |

| Hoesch-Archiv Thyssenkrupp Konzernarchiv |

| Landesarchiv Berlin Rheinisch-Westfälisches Wirtschaftsarchiv zu Köln |

| Sächsisches Staatsarchiv Chemnitz |

| Sächsisches Staatsarchiv Leipzig |

| Staatsarchiv Münster |

| Staatsbibliothek Berlin |

| Stadtarchiv Chemnitz Stadtarchiv Ingolstadt |

| Stadtarchiv Leipzig |

| Westfälisches Wirtschaftsarchiv Dortmund Wirtschaftsarchiv Baden-Württemberg Stuttgart |

Digitalization of Sources – Step I

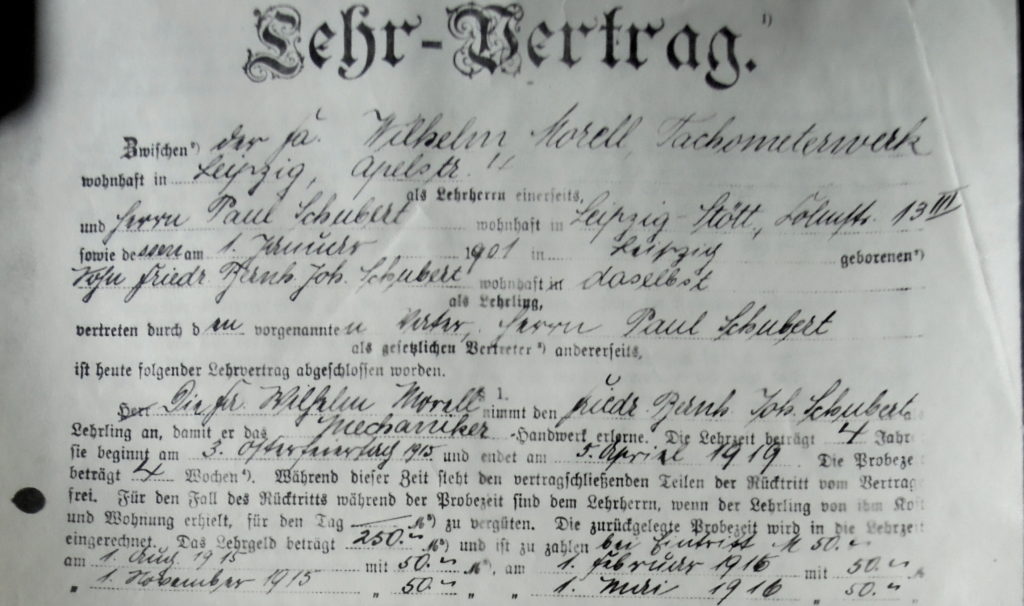

The sources are digitalized in a complex procedure. Two essential parts of the process are the OCR procedure and the TEI XML format. OCR (Optical Character Recognition) is a procedure through which an algorithm extracts text data from images. In other words, OCR ‘reads’ the pictures and converts them into machine-readable text, which can then be further digitally processed, as shown in the example below.

Digitalization of Sources – Step II

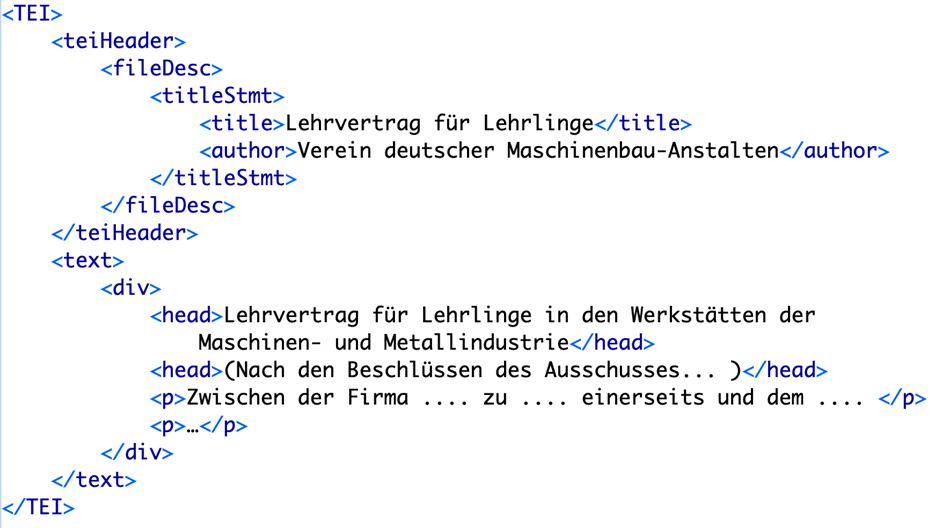

The texts are converted to a linkable structure via the TEI XML format. TEI XML is a standard file format for recording texts, ensuring straightforward use of the data by future researchers and long-term accessibility of the project data. Accordingly, this data format is the established one for editorial projects and is considered mandatory by the German Research Foundation (DFG). The use of the TEI XML format in our project has two important aspects. Firstly, the format is used for encoding text structure: The OCR process can at best capture the literal wording of the texts but not their organization into sections and paragraphs with different hierarchical levels. This structural annotation of texts is carried out manually and is very time-consuming.

Of particular interest is how TEI XML makes the annotation of chunks of text possible via certain key words (e.g. “Termination without notice”). To do this, the project team will select individual keywords tailored to specific source genres or create so-called keyword trees. By linking sets of regulations with individual rules, it becomes possible to gain insights into, for example:

- Time sequences and intensities of norm-setting (also in relation to specific regulatory content).

- Identification of particularly “highly regulated” or “innovative” associations and sub-sectors.

- Regulatory priorities, representativeness of individual normative statements.

- Ways of disseminating certain regulatory models or norm statements (knowledge and norm transfer).

- Possible regional or sectoral typologies or other special features,

- Relation to state law.

These investigative annotations were originally intended to be carried out manually. All sources would have to be worked through in detail by the research assistants and supplemented accordingly in all relevant respects. Since this would have been extremely time-consuming, an application was programmed which, among other things, enables the automatic annotation of all sources with keywords. This allows the number of keywords used to be significantly increased. From an experimental perspective, it has been shown that manual annotation (even when it is based on and carried out following automatic annotation steps) can only be achieved with a very selective topic-based choice of classification terms.

Digitalization of Sources – Step III

Since the source data with annotations are ultimately converted to the standardized TEI XML format, they can be made available to the scientific community and interested members of the public on an open access Internet platform, using free software without the need to develop significant tools

The main focus is on work regulations and collective bargaining agreements, as well as statutes and other regulations of workers’ associations and trade unions, statutes of company pension or health insurance funds, and employment contracts (either as contracts drawn up for individual cases or as model employment contracts). In addition, in the list under “other”), there are regulations primarily from employers’ associations, apprenticeship contracts, model rental contracts for company housing, statutes of employers’ liability insurance associations, training regulations, recruitment and dismissal guidelines, and regulations for other company welfare facilities. According to the current status of source indexing, the distribution is as follows:

The result is a database with the following advantages:

- simple, unlimited, free and location-independent access to a large pool of sources for scholars and interested members of the public.

- multi-functionality: filter options that make lines of development observable and comparisons possible; full-text search or annotations—depending on the type of implementation—that enable quick access to specific aspects of the source material; display options that also relieve people with an interest in individual companies/organizations or individual aspects of industrial relations of some of their search work.

- a sustainable database structure that also leaves room for future expansion (types of sources, companies/organizations, regions, expansion of annotations).

Progress and Costs of the Project

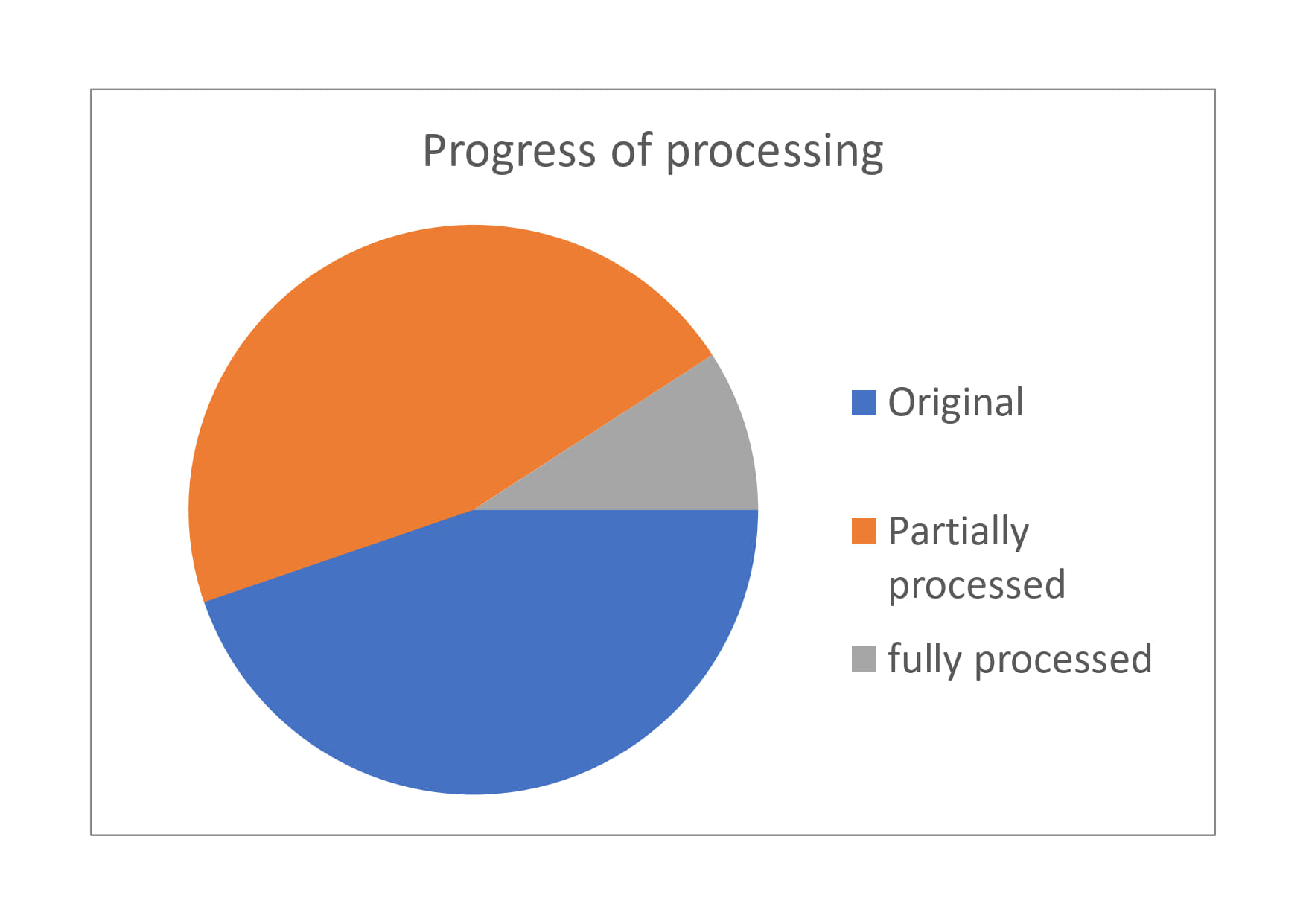

So far, ca. 800 sources have been recorded in total (as of February 2024). They are all in varying stages of editing:

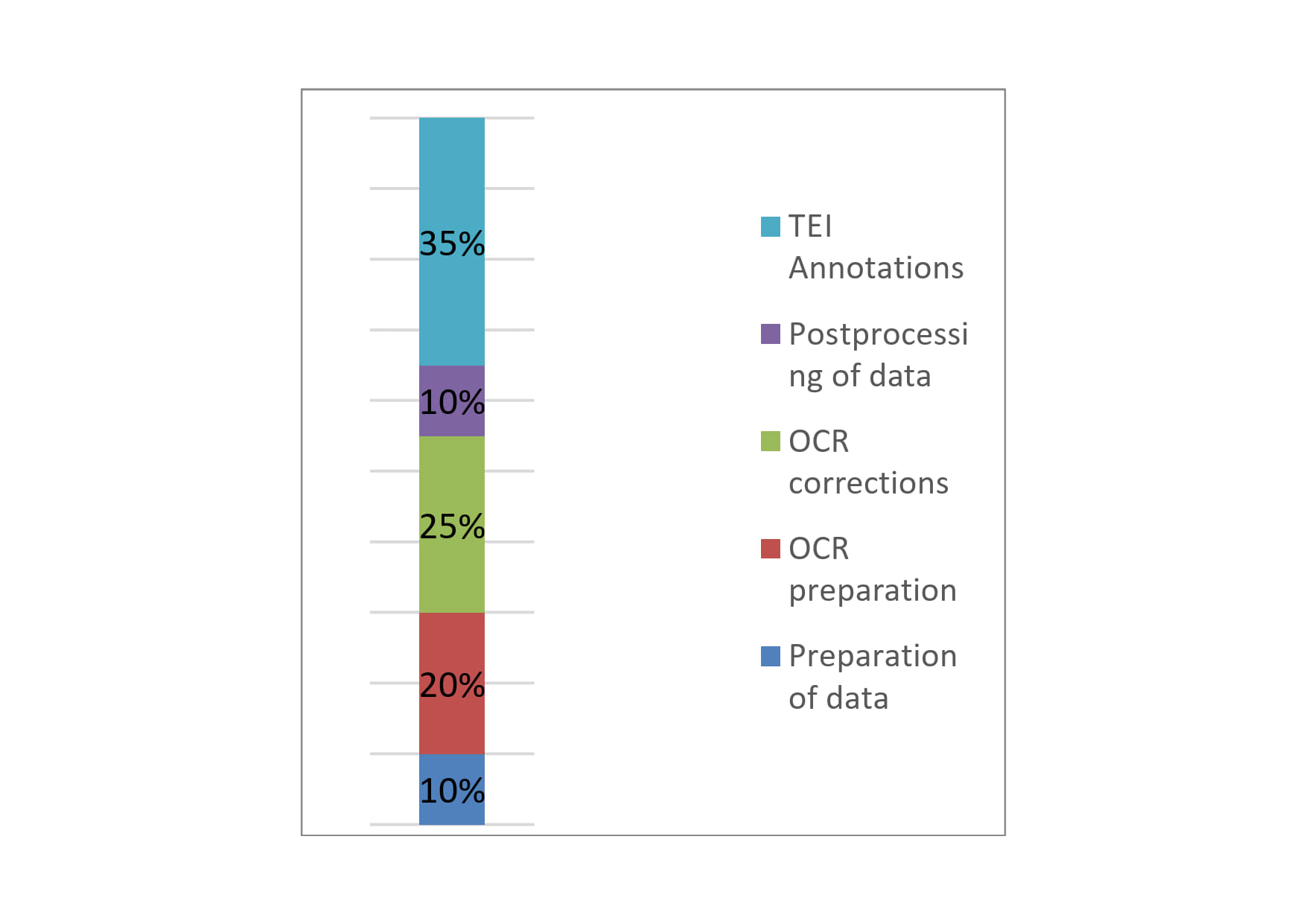

The technical processing of sources – i.e. the tasks that follow the research and image capture steps – requires several stages of work: During data preparation, the images created in the archives are rectified and prepared for OCR processing. The texts recognized by the OCR program must then be corrected and edited. The texts uploaded to TEI Publisher then undergo another correction process and are correspondingly annotated manually as described above. The percentages of workload are distributed as follows:

Simplified representation of the average time demanded by technical processing

Average page count per source: 13.6

Average character count per source: 23.600

Average standard pages (1.500 signs according to VG Wort) per source: 15.7

Average time spent on the total technical processing of a single source (Data preparation, OCR-processing, TEI annotation, and corrections) (estimate) 3 hr.

Perspectives

The edition project and accompanying individual projects taken together form an attempt at integrated legal, economic, and social historical research. Legal history is breaking away from its traditional fixation on legal sources and opening up to the consideration of norms that were previously classified as “non-law.” Such aspects were previously ignored or at least neglected. Looking not only at single statutes but also at many regulations of a similar kind (e.g. work regulations) makes it possible to derive general assessments and thereby reconstruct the normative order of the world of work beyond a single company. Economic and social history, in turn, integrate non-state law within the actions of economic and political actors. Individual studies can work out how rules were created, enforced, and communicated. They can then show how regulations were not only embedded in economic and socio-political disputes, but even determined or influenced them. The project can be linked to conceptual approaches in legal history as a history of normativity in several respects. First, multinormativity is illustrated, i.e. the coexistence of and interaction between legal (statutory) and (in the narrow sense) non-legal normativity. Second, a historical perspective on law and diversity is opened: It is understood how a group-based, special legal order was created within a legal framework that, from the beginning of the 19th century, was based on the principle of equality and aimed at the universality of its claims to validity. Third and finally, the order of the world of work can be described as a historical regime of normativity, i.e. as stabilized arrangements of discourses, practices, norms and principles and their contingent conditions in relation to a specific field of action. Observing these arrangements in work requires as much expertise in legal history as in economic and social history.

I thank Matthias Ebbertz, Lisa Marie Michel, Polina Solonets, Benjamin Spendrin, Tim-Niklas Vesper, Andreas Wagner, and Johanna Wolf for important factual advice and suggestions of style and wording.

This blog post is a translation of the original German version published in March 2023 and has been partly updated. Translated by Jonah Hirsch.

Cite as: Collin, Peter: Non-state Law of the Economy – A Collection of Sources, legalhistoryinsights.com, 18.04.2024, https://doi.org/10.17176/20240422-144536-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a