In the early modern period, being able to see the face of famous men of the time was essential. The need to know the physical aspect, went hand in hand with a physiognomic mentality that allowed to read in the facial features also some aspects related to the character. Particularly appreciated were the portraits from life.

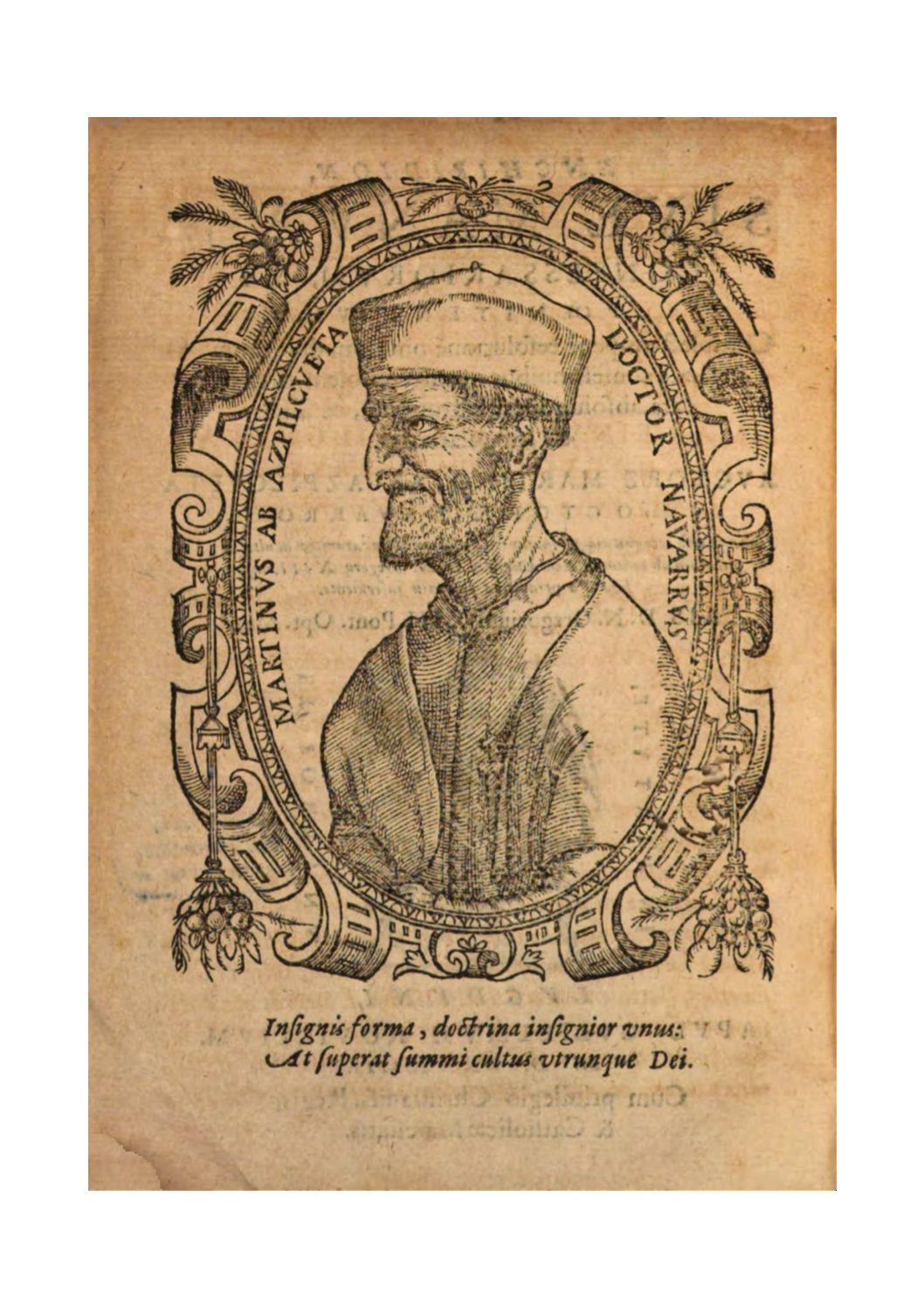

Not surprisingly, in the Rome of the second half of the 16th century, everyone wanted the portrait of Martín de Azpilcueta to enrich their gallery or add a pillar to their personal museum. To the point that, if we believe the sources of the time, the portrait with which we know today the physical appearance of Dr. Navarro, the celebrated author of the best-seller of the century, the Manual de Confessores, was made in secret. Azpilcueta, who at that time was an illustrious consultant of the Apostolic Penitentiary, did not want to be portrayed. Actually, he preferred to leave for posterity the portrait of the beauty of this soul, rather than the one of his body. But an artist was commissioned anyway and the work was completed.

The artist seems to be Antonio Lafrery, a well-known French engraver and printer active in Rome. For this portrait he is said to have worked with the engraver Philippe de Soye. As for those who would have commissioned the portrait, the sources do not agree, although one glimpses a certain provenance linked to members of Roman congregations, in particular the Congregation of the Index: some sources (including Azpilcueta’s biographer, Simon Magnus de Ramelot) speak of Cardinal Giulio Antonio Santori, who would have wanted the portrait for his collection; other sources speak of the Spanish Dominican Alfonso Chacon, to whom the King of Spain Philip II would have asked to set up a gallery of portraits for the Royal Library of El Escorial: In the index of portraits sent to El Escorial in 1587, Chacon mentions the portrait of Azpilcueta that he would have done in secret, and that was the source of the other portraits that circulated.

A famous version of the portrait can be found in the collection of portraits of illustrious jurists published in Rome by Lafreri from 1566 onwards (and since Azpilcueta arrived in Rome only in 1567 we can imagine that the portrait entered Lafreri’s collection after that date), largely taken from another private collection, that of the Paduan jurist Marco Mantova Benavides, and which ideally completed the biographies of illustrious jurists that Mantua had published a few years earlier. This seems to be the version from which all the other versions, present above all in the opening of the canonist’s works, were taken.

If we pay attention to one detail, the canonist’s hand, Azpilcueta seems to be holding a pen and preparing to write… Can this be a clue that confirms the story we have just told? That Azpilcueta was secretly portrayed, in the act of taking notes? Or is it rather an astute, carefully calculated, celebratory plan?

In any case, the portrait was printed in the frontispiece of the 1573 edition of the biography of Azpilcueta by Ramelot. Then, from 1584 on, the portrait would have opened the editions of the Manual, even those editions carefully supervised and checked by the Author, followed or preceded by the following inscription: “Insignis forma, doctrina insignior unus: At superat summi cultus utrunque Dei”.

Cite as: Bragagnolo, Manuela: The face of doctrine. The mystery of the “stolen” portrait of Martín de Azpilcueta, legalhistoryinsights.com, 15.06.2021, https://doi.org/10.17176/20210628-141423-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a