Many museums and archives contain collections obtained under colonial rule. The question of ownership rights of these collections has been much in the news over the past decade. The German Federal Foreign Office released its “Framework Principles for dealing with collections from colonial contexts” in 2019, and in 2021, the Deutscher Museumsbund released “Guidelines for German Museums: Care of Collections from Colonial Contexts.” In the news, the focus has been on the repatriation of cultural items, but papers of the colonial past have received far less attention from popular programs and magazines.

Roll back several years. When I first began to pursue my doctoral thesis concerning marriage and divorce in the German colony in Samoa, I naturally explored all the holdings of the Goethe University in Frankfurt on colonialism and post-colonialism. In addition to the university’s extensive colonial collections in its main library in Bockenheim (which include original copies of the newspapers and gazettes during the German administration’s period in Samoa, as well as a collection from the German Colonial Society including an online photo collection), there is a smaller but fascinating array of items in the Leo Frobenius Library of Cultural Anthropology in the basement floor of the IG Building on Campus Westend.

In a cool, dark corner of that library, in front of an A/V materials console, my heart froze while watching a documentary by German TV station ARD called “Reisen in die Vergangenheit – Auf Spurensuche in ehemaligen deutschen Kolonien : Papua-Neuguinea und Westsamoa.” German reporter, Felix Kuballa, was taken to where the papers from the German government were kept. His Samoan guide led him to an old, derelict building where myriads of boxes of moldering papers vomited forth unceremoniously among the rubble and cushioned in the humid air. With trembling fingers, I turned over the back of the cover to see that the documentary was from 1998. I wondered if this was the end to my research, and if anything regarding matters of family law remained.

Since I handed in my thesis earlier this year, I can tell you – thankfully – that this worry was superfluous. I still don’t know if the files in the documentary really were the papers of the administration (I had also learned that the archives in Samoa were established before 1996, thus I am now uncertain what those boxes in fact were). But by the time I visited, the part of the papers left in Samoa were being handled with appropriate archival care by the highly skilled archival team of Samoa’s Ministry of Education, Sports, and Culture (MESC).

Accessing the Archival Papers in Samoa

When the British occupied Samoa at the advent of World War I, they seized the files and papers of the German administration. Some of those files are in the archives in Wellington, New Zealand, and the others are in the Samoan archives. Other archival materials – for example, personal files and correspondence of members of the administration and files of the Colonial Office – are in the German Federal Archives in Koblenz and Berlin-Lichterfeld. I have visited all of these archives, but here I will focus on my time at the archives in Malifa, Apia, Samoa.

The archives in Samoa are not freely open to the public; the government must approve a request to visit the archives for research purposes. Once I had found out about the archives, I sent an email to the MESC stating my research topic and asking how I could visit the archives. They sent me a form to fill out concerning my background, institution, and research topic; essays and short answers were required about why I needed to access the materials and for what I would be using the information there. After submitting the completed request form, I waited several weeks for approval. The excitement upon receiving a positive response was real – since there was no complete index available at that time to send to me, it was truly going to be an adventure of exploration!

The head archivist, who was encouraging and a great help in the preparation for the visit, contacted me. The biggest challenges to research did not lie in the archives nor in the materials themselves, but in my time constraints. I was pregnant at the time, and then the airline rules were such that I should return within eight weeks of the due date. I needed to work efficiently every weekday and suppress the urge to go down too many “rabbit holes” of curiosity. The archival team prepared in advance for my visit and made it the ideal place to buckle down and work.

The Archives of the MESC

At that time, the archives in Samoa were held at the Ministry of Sports, Education, and Culture (MESC) headquarters building in the Malifa area of Apia which is about a kilometer south of the harbor and downtown area.

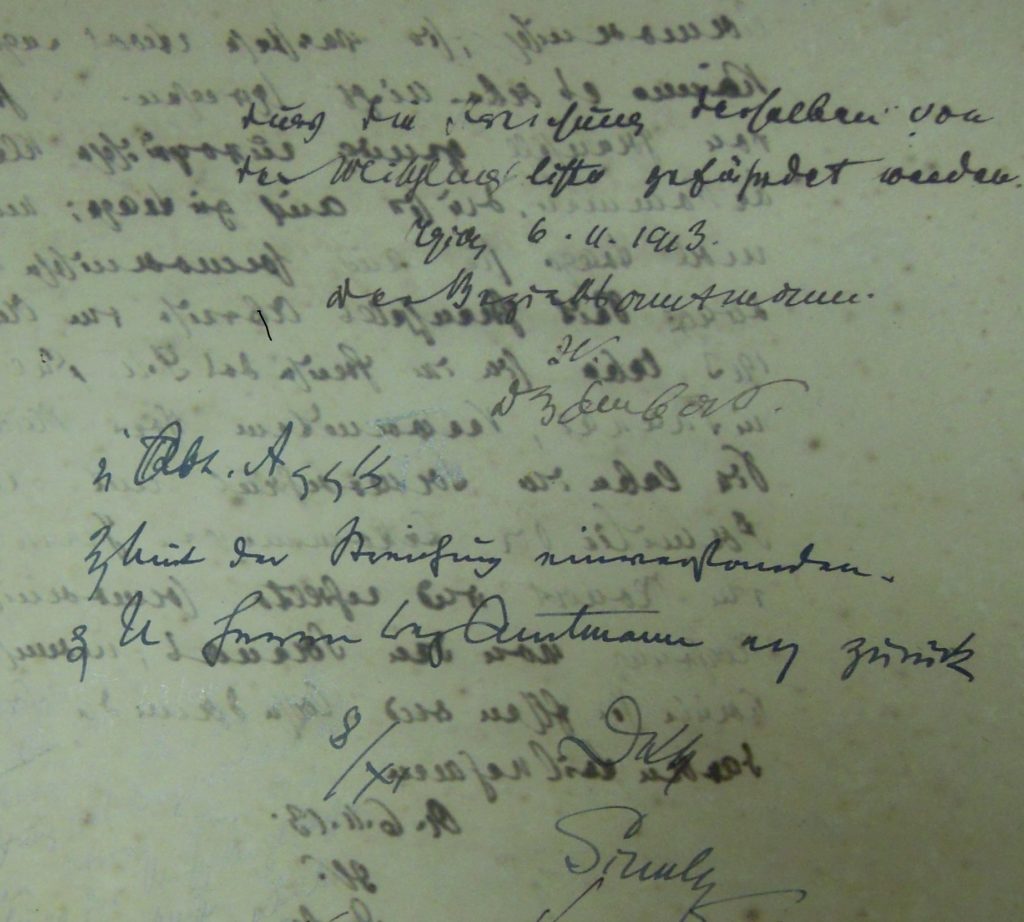

The files in the Samoan archives were held in a single, spacious, air-conditioned room. The head archivist and her team made me feel very welcome. At time of my visit, the archives had a new digitization camera which had been funded by the German government, but the funding was limited and the camera was broken when I was there and awaiting repairs. Thus, the usual care in working with archival materials was necessary: clean gloves, patience, and delicacy. During the British military occupation, some files were taken to New Zealand, including criminal files, civil law cases involving foreigners, etc. Other files, including the “half-caste register” discussed at length in my thesis, extensive files related to combating the invasive rhinoceros beetle, Samoan divorces, personnel files, and more were left in Samoa. Needless to say, I was once more thankful that these files were receiving the conservation efforts they deserved. Almost none of the pages were typed – most had been written in German Kurrent, an obsolete cursive handwriting, and probably due to humidity and previously poor storage conditions, many pages had suffered from bleeding ink and so I photographed them with a high-resolution digital camera for later analysis and transliteration.

German Kurrent is a form of handwriting that is very difficult for most modern readers to decipher. It is somewhat similar to its successor, Sütterlin handwriting, but Kurrent can often have a more cramped and vertical appearance which makes it especially difficult to read when blurred by humidity. Kurrent required a quill to master its fine, nuanced strokes. After looking at hundreds of pages of this handwriting, I can only say that fresh quills must have been in as short supply as fresh Kaiser Wilhelm apples for apple cake.

The handwriting on the documents actually was part of the puzzle in the legal research. On one hand, because the documents were handwritten and also poorly affected by the environment prior to being in the climate-controlled archives, reading or transliterating them could be challenging. But even though the reverse side of the page often bled through, because they were handwritten, the emotions sometimes bled through as well. Although the exact situation is speculative, one could not help but read impatience in imprecise handwriting with “Eilt!” written in margins, or frustration and annoyance in judicial decisions when the lettering on certain sentences becomes thicker and darker as the author pushes the quill harder into the paper. One valuable tip which a professor gave me later during the analysis phase was not to overlook notes in the margins. There were many notes in the margins, and lines crossed out, all of which were like golden tessera.

Throughout the entire trip, I was made to feel very welcome. A judge gave me a tour, and offered valuable insight, advice, and references for my research. One particular historic case which he copied from his library referenced a Malietoa law referenced in my thesis which has since been – as far as I could discover – lost in its original form. Likewise, the librarians in the public library – which also has several holdings from the colonial period – were helpful. The German consul gave me a personal tour of the former Apia Courthouse and of the Museum of Samoa. The dim, quiet courthouse smelled of earth and musty wood which once had been filled with the sound of foreign languages and men in long-sleeved white suits with wire-rimmed spectacles, ruddy faces, and beads of perspiration around their temples. This two-story, L-shaped wooden building with worn white paint survived cyclones, tropical climate, and the march of time only to be demolished in 2020. Incidentally, its destruction was one that was hotly contested, as some wished to preserve it as a part of cultural heritage while others viewed its prominence near the harbor as a painful reminder of the colonial period. I am thankful that I had the opportunity to visit it while it was still standing.

The Future of Archival Papers

Since that time, the archives have expanded and the digitization is well underway. The new National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) now oversees the archives, which has an increased focus on digitization, and the archives have moved to a larger area.

A 2020 documentary about the archives (in Samoan language) can be viewed on the Facebook page of the MESC. The second half of the video shows the archivists displaying samples from the archives. A more recent video from 2022 commemorating the International Archives week can also be viewed. Public exposure and attention to the paper treasures the Samoan archives hold seems to be gaining more and more momentum. While archival documents generally have received less attention than cultural artefacts in the past years, they are no less material to important public questions of today, like those of ownership rights in colonial contexts. Preserving these documents is vital for gaining insight into these contexts, not to mention for the preservation of histories in general. Luckily for my research, the value of these papers were recognized and handled with great care in Samoa and, despite certain challenges, I was able to engage with this particular (German-Samoan) colonial past and hopefully provide some contribution to these important questions.

Cita as: Hütten, Julia: Papers of Pacific Colonial Pasts: a visit to the national archives in Samoa, legalhistoryinsights.com, 02.09.2022, https://doi.org/10.17176/20220902-131900-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a