One of the pleasures of being a legal historian concerned with topics from the early modern period is the possibility to get to handle and work with historical books, often originals printed in the 16th and 17th century. Too often, we tend to concentrate exclusively on the content of a book, not taking into account the wealth of information stemming from the materiality of the book: who printed it, how it was printed, and how the materials carrying all the precious content were produced. For the early modern legal texts, Manuela Bragagnolo sensitizes us in her projects for this material dimension to our sources.

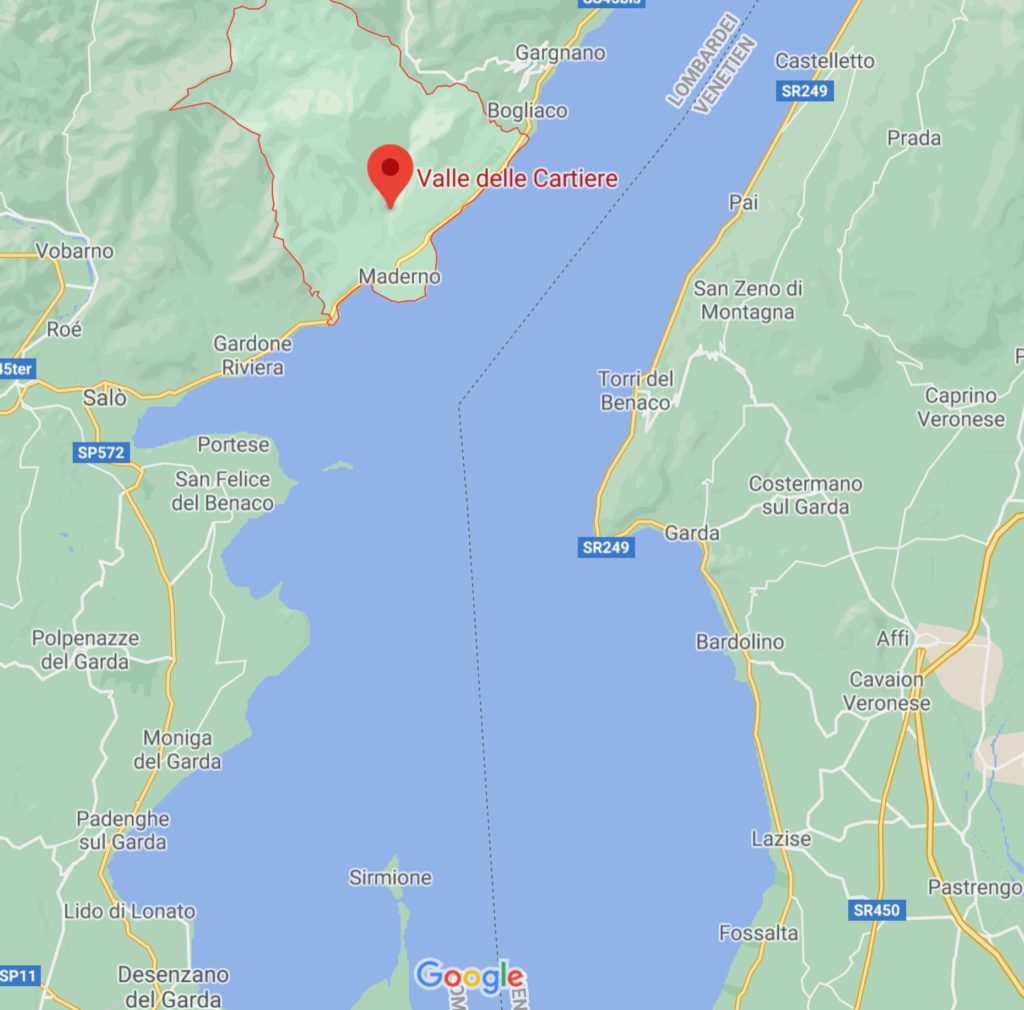

But sometimes, reminders of the books’ materiality come from a quite different angle and they can be found in unexpected places, even when touring the region of Lake Garda for a holiday. Near its Southern end, on the western lake shore and at the outskirts of modern Toscolano Maderno, a small street leads into a narrow valley, the so-called Valle delle Cartiere.

Before passing the first tunnel leading into the valley, a sign forbids any entry on rainy days: the rocks are fragile and prone to stone slides when slippery wet. If the weather is friendly, one can proceed through two or three narrow tunnels lead deeper into the densely wooded gorge.

Soon, the car has to be parked; the valley itself can only be discovered on foot or by bicycle. The small gravel road leading through the valley was built in the 19th century; before, only a narrow boardwalk allowed access to the inner depths of the valley, navigable only on foot, with donkeys as the only means of transport. It is hard to imagine that for centuries this idyllic valley, with its atmosphere of remote tranquillity, has been one of the hubs of paper production in Northern Italy. The Toscolano River, which flows at the bottom of the dell, today is only a slight brook, due to the dam built in 1962 at Valvestino. In former times, the river had a much higher rate of flow, quite enough to drive one waterwheel after the other in its course through the narrow valley down to the lake.

Paper production at Toscolano begins in the 14th century with the establishment of the first paper mills which catered for the modest paper markets of the neighbouring areas. The exact foundation dates of the first paper making establishments in the valley is unknown; it is supposed that their founders came from other parts of Northern Italy, probably from the region of Treviso or Padua where records of paper production can be found from the end 13th century (Treviso) respectively from 1339 (Padua, cf. Mattozzi 1995, 26). The earliest document mentioning a paper mill in the valley of the Toscolano River dates from 1381, an agreement about the partitioning of the water rights (Mattozzi 1995, 26; Fossati 2001, 133).

During the 15th century, at least ten paper mills are said to have been built or opened in the valley (Fossati 1941/2001, 134 who, however, does not cite any of his sources, an omission commented upon by Mattozzi 1995, 27), and from 1470 on, a noticeable economic growth can be observed, an intense period of paper production, diversification of products and establishing a net of wide-spread trade connections. Indeed, competition becomes so intense that in the 1470s, a number of maestri cartai leave the Toscolano area to establish themselves in other Italian cities, thus hinting at a certain saturation of paper mills in and around the valley (Mattozzi 1995, 28). Production of paper in the valley reaches a peak regarding the number of paper mills and the quality of the produced paper when between 1507 and 1540, at least ten new paper mills are built (Mattozzi 1995, 28). During the 16th century, no less than seventy families of the Toscolano region send members to Venice and other Italian cities to establish case di commercio, selling the paper widely abroad. The most important Italian markets for Toscolano papers are Venice and Padua, but also the international trade takes off, with Toscolano products being sought after in Vienna, Moscow and even Constantinople where the durable paper from Lake Garda becomes the standard material for the firmans, the decrees of the Ottoman sultans (Fossati 1941/2001, 135). Some scholars say that the development of Venice as a European centre of printing and bookmaking was intimately connected to the availability of large quantities of paper as brought from Toscolano, i.e. paper of an exceptional quality, competitively priced (Mattozzi 1995, 31 sqq.).

This first boom time in the valley only grinds to a halt with the arrival of the plague in 1630 which leads to a paralysis of all enterprises. Even afterwards, as production dwindles and paper mills decline, fortunes take a sharp turn for the worse for almost a century. Only in the 18th century, the economic situation grows livelier again, culminating in a thriving paper mill community in the 1770s and 1780s. And again, in the 18th century, paper from the Toscolano mills is sold and renowned in the whole Mediterranean region, so that the Venetian ambassador to the Ottoman Empire reports in 1755 that the sales of this paper are excellent throughout the Levante. Six years later, the products of the Toscolano mills are said to dominate the paper market as far away as Aleppo, being of a superior quality to the contemporary French papers on offer (Matozzi 1995, 47). Only in the modern era of industrial production, the traditional paper mills of Toscolano slowly wind down, and by 1945, their economic importance had dissolved.

Today, the former busy centre of paper production has become quiet and green, the Toscolano River is no longer a powerful stream, but has dwindled to a tinkling brook, most of the time hidden in the dense foliage at the bottom of the valley. Hiking through the valley, one can explore the ruins of some paper mills; others are closed off from the tourist, and often only small traces of stone walls hint at the mills, the workers’ houses or the villas of the proprietors which all stood here in more glorious times.

Not far into the valley, one of the biggest former mills has been lovingly renovated and converted into a museum (Museo della Carta di Toscolano Moderno) reflecting the artisanal and industrial wealth of paper making in the area.

Literature

Donato Fossati: Benacum. Storia di Toscolano (1941; edizione anastatica: Toscolano Maderno 2001).

Ivo Mattozzi: Il distretto cartario dello stato veneziano. Lavoro e produzione nella Valle del Toscolano dal XIV al XVIII secolo, in: Carlo Simoni (Ed.), Cartai e stampatori a Toscolano. Vicende, uomini, paesaggi di una tradizione produttiva (1995), 23-65.

Cite as: Birr, Christiane: Producing Paper for Venice: The Valley of Papermills (Valle delle Cartiere), legalhistoryinsights.com, 25.08.2022, https://doi.org/10.17176/20220825-131053-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a