This year’s Summer Academy went by in a two-week flurry of intensive, interactive and inspiring discussion. While this is perhaps no different to previous years, after a two-year break and the certain disappointment that went with those postponements, the simple joy of being together— not to mention with bright, engaging people— was surely heightened.

How to summarise those two weeks? It is so much more than a reading of the programme can reveal, of course, although this does provide good insight into the variety of topics addressed by the participants, researchers at the MPILHLT and the guests. Some consolidation to this variety could be found in this year’s theme “Using History in Law”. So, what was this topic all about?

Some basic assumptions underlying “Using History in Law”

“Using History in Law” is a way of looking at past legal orders, that is to say a perspective or point of observation that highlights the way in which actors use or value or refer to history when dealing with the law. With this perspective, we consider “Using History in Law” to be a kind of resource which entails the extraction of past normative knowledge by certain actors in order to, at the same time, produce – which production could also or instead be a re-affirmation, reconstruction or a rejection of – the law.

Before looking at concrete examples of this phenomenon, it would be worth it to begin with some fundamental starting points. We need to elucidate some of our assumptions about the law, about how we think about it, and about how legal knowledge – how we know what the law is and what to do with it – comes about.

How do we know what to identify as belonging to the law and what sits outside of it? How do judges and lawyers know what to say in a courtroom, how do they know what to translate from fact to legal argument? The question is not where is the line that defines the law – this is a classical question for legal theory – but rather how did that boundary develop or change? A question of legal historical epistemology.

For a long time (and, I would argue, even still in law schools) it has been taught that the law has a capital “L” and is deemed something almost sacred and untouchable. My and certainly others’ legal education was premised on the idea that the thing that lawyers and judges do is to select the relevant legal principles from the body of law that exists in the country and apply those principles to a set of “real world” facts that your client or the parties lay out for you. The idea that there may be a process of translation involved in what is fact and what is considered a fact for the law, that the law may be very much constituted and influenced and determined by those facts, was not acknowledged. Facts were separated from Law and the skill we were taught was to identify which legal principles were relevant given the case.

This not to say that my law professors denied that the law had grown out of the past and evolved to better suit contemporary interests. But the idea remained that once those principles were written down in a judgment or a piece of legislature, they obtained a certain elevated status. They became authoritative and existed abstractly, generally applicable across the ages.

So what, then, is an opposite idea to the law having a capital L, as being an abstract thing that exists above and outside of the nitty gritty messy facts? Well, that the law is exactly those nitty gritty messy facts: the people and institutions and communities and practices and communication and material things – like papers and files and books and notes and words and objects – that are down to earth, so to say, tangible, touchable, can be seen and heard.

This is a constructivist view of the law and how it comes about. And this is perhaps a lot more natural when we look at legal systems of the past because part of our research process is to deal with sources, that is, with the tangible evidence left over from legal systems.

Being legal historians, we are interested in changes in the law over time. So, what we can then ask is how did these down to earth things develop or contribute to the legal regime we are analysing. We get rid of the idea that what is written in a book is only representative of a principle of law, but that it is that book itself, as it was copied and shared and read and used by legal communities, that is law. And with this in mind, we can physically trace the developments and changes in legal systems and say something quite true about what the law is or how it developed over time.

Where is “Using History in Law” thus positioned?

So, now we have the idea that law is made up of things, institutions, architecture, people, practices, communities. Furthermore, they do not exist in isolation, but are interconnected in various ways, often if not always feedback looping and influencing each other. This is complex. Where do we even begin? Well, you start small. You can identify and extract one of these phenomena and focus on that and trace it in your sources. Such a process is artificial, of course, and there are limitations in this method because you will only be able to access part of the whole picture. But this type of analysis is one of the only tools we have to understand a complex world.

So, we could look at communities of practice, we could look at institutions, we could look at material objects, and we could look at the phenomenon of “Using History in Law”.

This is where the theme “Using History in Law” is situated for us – as one part of a complex historical legal regime, a part which not only makes up what we see as law, but is also used as a resource to define or change or produce law.

Furthermore, and confirmed by the varying times and places presented by the participants and researchers during the Summer Academy, the phenomenon of “Using History in Law” is nothing recent. It may not even be radical to suggest that ever since societies have had legal histories or legal traditions, they have been interested in and often in reverence of what the past can tell us about the law. Not only is the past important as a guide or explanation for present legal practices however, it can also be used for specific purposes. Identifying and relying on a certain piece of historical information may, for example, give authority to a legal argument, be used as justification for certain behaviour, legitimise or delegitimise a legal norm or solve some legal practical issue. It may also have many different consequences such as the past becoming reinvented or reconstructed for legal purposes, the significance of a part of history being understood for the first time in a new legal context, or the solidification of legal identities, to name a few.

An example from South African legal history

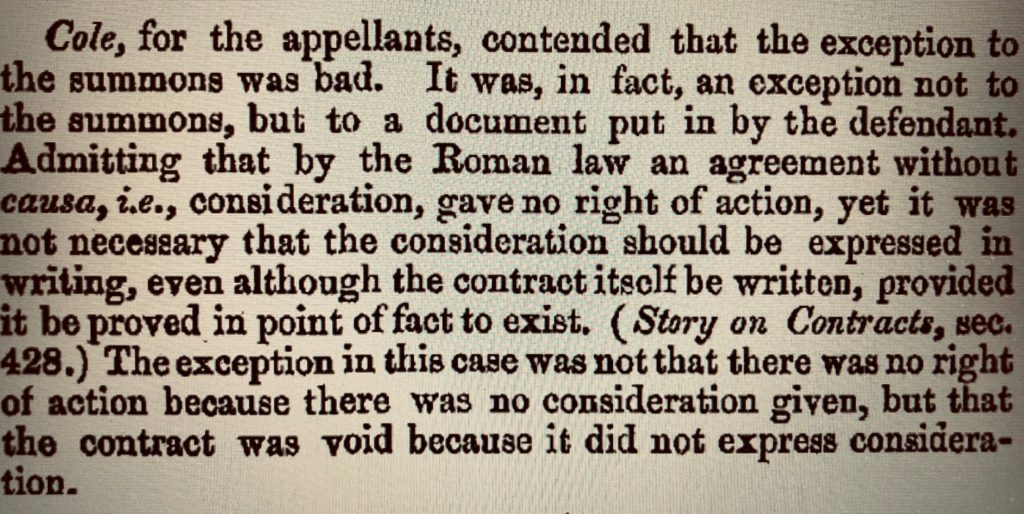

Towards the end of the 19th century, there was a debate in the courts of the Cape of Good Hope and the Transvaal (before the country became South Africa) about whether or not in contract law, the English doctrine of consideration (so, the requirement for a quid pro quo between the parties to support the agreement) was applicable in the Cape. This is a time in South African legal history when English common law practices and principles had deeply infiltrated the legal system that had been established by the Dutch colonisers, thus the question of the applicability of common versus Roman-Dutch law often yielded heated debate. With regard to this question, early cases of the Cape Supreme Court in the 1830 and 1841 implied that no consideration was necessary, but that iusta causa – following the Roman-Dutch law on the matter – was a requirement for a valid contract. In other words, the parties must have had a just cause for entering into a contract, that is, both parties must have seriously intended to create binding obligations, in order for that contract to be enforceable.

The same court then in 1874, in a very short judgement, equated consideration with iusta causa based on an argument by counsel. The Chief Justice referred only very briefly to Roman-Dutch authorities, did not mention the previous case law I just referred to, and said that “the law should not enable a person to enforce a contract for which there had been no consideration at all”. This decision was followed in at least four subsequent cases, the last of which further elaborated on how this was consistent with the Roman-Dutch authorities of the past.

Then, in 1904, the Transvaal Supreme Court (one of the supreme courts in another part of the country with equal status to the Cape Supreme Court) relied on substantial use of Roman-Dutch writings and decided that consideration was not equivalent to iusta causa, that the Roman-Dutch writers had always used the term more broadly, and that to implant an English doctrine into our law would be in conflict with Roman-Dutch principles.

Both sides of the argument relied on Roman-Dutch writers. Two of the highest courts in the country, through the judgments of two of the most respected and learned judges in the country, used the “same” normative information from the past, the same history, to argue two different things. What happened? The Chief Justice of the Cape court, the main advocate for the position that consideration was part of the law, died and his successors went the other way in a long judgment which set out the history of the debate in the case law of the country, as well as a discussion of Roman and Roman-Dutch writers.

Concluding remarks

So here is an example of how history is used in law to achieve certain purposes. We see that history can be malleable, used here either to elevate English legal doctrine or that of Roman-Dutch and then to argue that this is or should be the law of our country. And what we can further see is that the past – however it is understood or interpreted – is a necessary element of the law, is given such great weight in defining and understanding the law that without reliance thereon we would be left with very little ground on which to make claims about what the law consists in. To repeat, the past is a resource from which we extract normative knowledge and then at the same time produce – which can also be a re-affirmation, reconstruction or a rejection of – the law.

A range of other examples of “Using History in Law” can be seen from the method of legal interpretation called originalism in United States constitutional law when applied to indigenous communities. Originalism draws on the pre-colonial pasts of indigenous communities to argue for original traditional and customary rights, from the state-approved accounts of history inscribed in “memory laws” to more general ideas about the law as immemorial custom and thus authoritative by virtue of its antiquity.

If we, as legal historians, are concerned with changes in law over time, we can look at the phenomenon of using the past as a specific feature and source of legal change. “Using History in Law” can be seen as a means by which actors not only understood the law but also contributed to its transformation. One task of legal historians therefore could be to understand the historical conditions and contexts under which the actors we study engaged in using history in law.

Cite as: Woods, Alexandra: What was the theme of this year’s Summer Academy, “Using History in Law”, all about?, legalhistoryinsights.com, 16.09.2022, https://doi.org/10.17176/20220916-154928-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a