Research in the humanities is not disruptive, as it can be in the natural sciences. Nevertheless, it is not static. It is a mark of quality when new questions arise from continuous work on specific sources and problems. In many cases, the critical examination of the research tradition and methods of one’s own discipline leads us to discover new sources and allows us to see things that we simply did not have in mind before. For example, in legal history, for a long time, we only paid attention to institutions and little to actors, and since new actors (or new “epistemic communities”) have come into view, the perception of law and its history has also been changing. We have often written the legal history of the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period only as a prehistory of modernity, and after the teleological assumptions therein became clear, our understandings of legal history before modernity also changed. Finally, global history has made us aware of the dangers of applying categories and fundamental concepts that derive from a European worldview: we cannot simply apply our notions of space, historical epochs, law, relevant actors, or the state to other regions of the world, as we have long done.

From European Legal History to Global Legal History

Since 2010, when we began to observe legal history from a global perspective at the Max Planck Institute for European Legal History, we have sought to implement this decentralization of categories and basic concepts.

The process was gradual. We first set observation posts outside Europe and looked at legal history from there. Doing so expanded the focus of legal history beyond that of the existing academic tradition, which led to the statehood of modernity and was primarily a history of private law and public law. We have integrated canon law and moral theology into our observations and thus tried to overcome the state-centered perspective. At the same time, we have strived to develop methods for writing a non-diffusionist legal history by implementing concepts of cultural translation, multinormativity, glocalization – summed up under the term “global legal history”.

Even though we have endeavored to analyze the entanglements between Europe and other regions of the world, we started our work focusing on Europe and Latin America. The reason for this was simple: even global history is only good if it is at the same time very good local history, and this requires knowledge of sources, languages, and the building of a research community. We have been fortunate to build such new communities, for example, in larger projects on the history of canon law in Hispano-America and the Philippines, on the history of the Roman Curia, on the School of Salamanca. We consider it a privilege that scholars from all continents now work in our department. In addition, over the past several years, former PhD students or postdoc researchers in our department have received tenured or tenure-track positions in Chile, Mexico, the USA, Italy, Spain, Germany, Austria, Netherlands, Belgium and China. In three cases, we were able to set up Max Planck partner groups and thus consolidate cooperation – first a partner group in Santiago de Chile, then in Trento, and in the next months in Beijing. This denser network of cooperation with local communities is strengthened by our guests, some of whom have worked on projects for many years and now work with us from Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, China, Chile, Italy, Colombia, Peru, Switzerland, Spain and the USA.

Because of our natural expansion, the spaces in which we work have also expanded over time: the focus on Latin America has become the Iberian Worlds, including Asia and Africa. Concurrently, we have also continued projects on legal history in Germany concerning a wide range of topics such as the Middle Ages, special legal orders, and labor law in the 19th and 20th centuries. Not least through the discourse with and between these different projects, our ideas of a theory-sensitive legal history have evolved and developed, for example with regard to non-state law and its sources.

Historical Regimes of Normativity

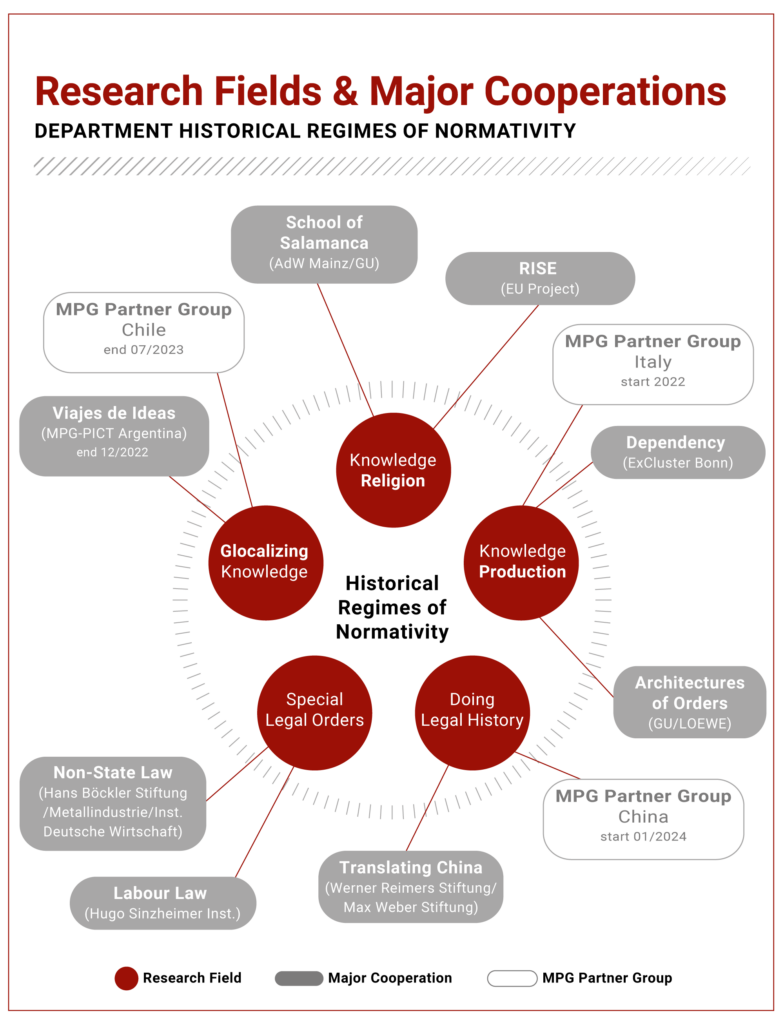

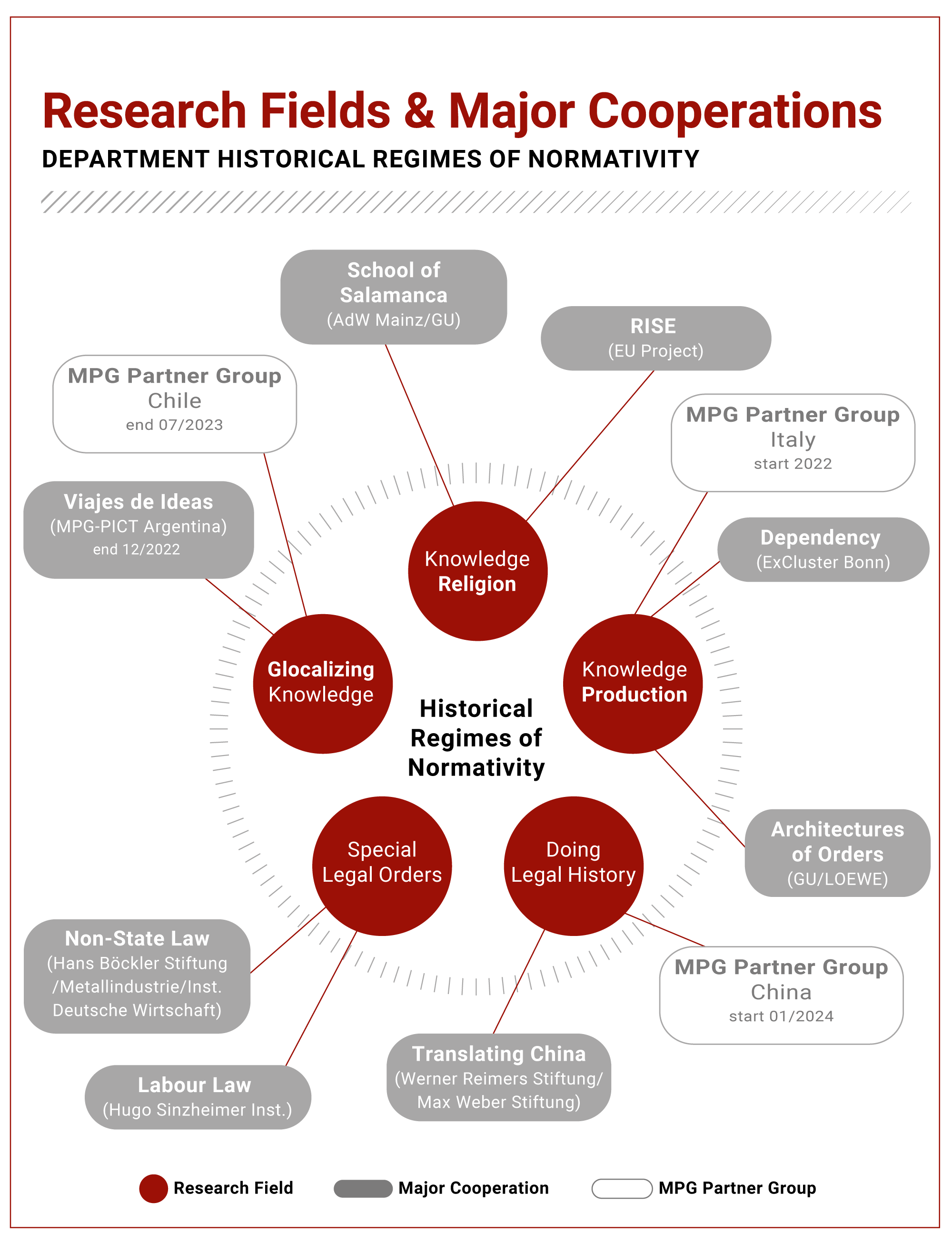

By renaming the institute the “Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Theory” and naming Department II (Duve) “Historical Regimes of Normativity,” we have taken a further step along this path. When we refer to our research as observing “regimes,” we are making a link to earlier projects on regulatory regimes; when we observe “normativity,” we are building on our discussions of a method for a history of law in global perspective. We have explained this in more detail in a series of blogposts with the initial results of a Regime Theory Working Group. Finally, in recent years, we have formulated this method in the language of the history of knowledge: we understand legal history as a history of translation of knowledge of normativity, which by necessity must include practices. We observe these processes of translation as “regimes”— that is, as stabilized arrangements of knowledge of normativity. Rather than limiting ourselves to one nation or empire, we have set up observation posts in various places in the world and describe what we see with the help of this language. Our hope is that by doing so we will go beyond deconstructing Eurocentric analyses. We also develop a method for legal history in global perspective and accordingly test and advance it in concrete research contexts (see Duve 2021 – German – and 2022 – Spanish).

A New Research Profile

Changes in personnel, the conclusion of some research projects especially on criminal law, the expansion of research to different world regions, and the consolidation of a method for global legal history research, all made a change in the research profile necessary and possible. We now have the chance to structure our activities according to problems and questions independent of spatial classification (“Iberian Worlds”), European categories (“history of criminal law”) and periodization (“Middle Ages”).

In the research field “Knowledge of Normativity from the Sphere of the Religious”, we look at the interconnectedness of what is called, in the Western tradition, “religion” and “law”; in the research field “Glocalization of Knowledge of Normativity”, we focus on the processes of globalization and localization of knowledge of normativity through translation; in the research field “Knowledge of the Production of Normativity”, we look at the mechanisms of the production of knowledge of normativity. In the research field “Special Legal Orders” we analyze organizational forms and structures of orders. Finally, in the research field “Doing Legal History” we reflect on the connection between media and legal historical research and at the same time develop new forms of scholarly work and communication.

This new research profile is a logical translation of our method into an organizational structure. It is meant to stimulate conversation, open up common perspectives, and serve as a meeting place for scholars from different regions and traditions. It should facilitate understanding one’s own research results not only as part of the state of research usually structured around specific places, periods, and topics (for example, as a contribution to research on the School of Salamanca, the history of canon law, the history of labor law, the legal history of Latin America, etc.), but it also should help to reflect on one’s own research in light of the common method. Structuring our method in this way should offer innovative potential for any project and at the same time serve our common project of writing a “legal history beyond modernity.”

Bibliography

Duve, Thomas, Von der Europäischen Rechtsgeschichte zu einer Rechtsgeschichte Europas in globalhistorischer Perspektive, in: Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History 20 (2012) pp. 18-71, http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg20/018-071

(Spanish: Los desafíos de la historia jurídica europea, in: Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español 85 (2016) pp. 811-845, https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/anuarios_derecho/abrir_pdf.php?id=ANU-H-2016-10081100845

Duve, Thomas, Global Legal History. Setting Europe in Perspective, in: Pihlajamäki, Heikki/Dubber, Markus/Godfrey, Mark (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of European Legal History, Oxford: OUP 2018, pp. 115-139, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198785521.013.5.

Duve, Thomas, What is global legal history?, in: Comparative Legal History 2020/2, 73-115, https://doi.org/10.1080/2049677X.2020.1830488

Duve, Thomas, Rechtsgeschichte als Geschichte von Normativitätswissen?, in: Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History Rg 29 (2021), pp. 41-68, http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg29/041-068

(Spanish: Historia del derecho como historia del saber normativo, in: Revista de Historia del Derecho 63 (2022), pp. 1-60, online: http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1853-17842022000100001

Duve, Thomas, Legal History as an Observation of Historical Regimes of Normativity, in: Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory Research Paper Series No. 2022-17, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4229345

Duve, Thomas, Legal History as a History of the Translation of Knowledge of Normativity, in: Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory Research Paper Series No. 2022-16, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4229323

Cite as: Duve, Thomas: Why a new research profile for the department of Historical Regimes of Normativity?, legalhistoryinsights.com, 05.12.2023, https://doi.org/10.17176/20231206-174158-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a