The power of the past

We all refer to the past – our personal histories or national histories or even global ones – to gather some certainty or to inform some objective that is significant to the present. Legal history and legal historians are no exception. Most of us can agree that what legal historians do is pick a time and place in the past that is of some interest to the law, gather the sources relevant to this particular past and, then, tell its story today.

But what really happens in this story-telling? Do we create a narrative that is in fact inevitably and always an interpretation, subjective and therefore not a scientifically valid truth? Or is such extreme hermeneutics quite preposterous in light of the black and white facts of the past, of monuments, of manuscripts and letters, of books and objects, of the very basis of the entire discipline which is a hard empiricism? Do we really gain access to a past, something that is objectively discoverable and therefore authentic, reliable and true? Or are we conditioned by our own present mental categories? What do we do when we use, gather, document, record and write legal history?

These questions are not only theoretical; they can have a political effect. Hence the question which was asked during the 2019 Summer Academy of the mpilhlt: “What is the role of the legal historian in the age of increasing populism when national histories, and constitutional histories, are used in public debates?” This I will try to answer from a perspective that is personal, based on my own past and the country I am from: South Africa.

A South African perspective

The perspective of my home country requires not only that I provide a little constitutional history and contemporary examples, but also share some personal experiences. So, I ask forgiveness for what is a subjective standpoint. I am still learning. But I do know that it is only from this personal point of departure that I can begin to paint a picture of the diverse and complex country we call “The Rainbow Nation”. I will stick to South Africa’s contemporary history and give a few examples of what we could describe as populism, perhaps even a kind of nationalism, and thus also see the different forms they come in.

In 1994, we had our first democratic elections. I was five years old and my biggest concern was for my dad to buy me the new mermaid Barbie with gold sparkly tail – hairbrush included. South Africa was to be governed by the African National Congress (ANC) under the leadership of the country’s first black president, Nelson Rolihlana Mandela. Mandela and the ANC were, and remain to this day, symbols of the Struggle, of resistance, of revolution and of hope for millions of South Africans.

During the early years of Apartheid (the Afrikaans word for “separateness, apartness”) which lasted roughly 50 years from the 1940s until 1994, people like and including Mandela were involved in grassroots protest action, including boycotts, strikes and many clashes with the police. Under the strict and unjust laws of Apartheid, such popular action became more unified, developing in some sectors into a kind of nationalism among previously separated groups – groups which under the 1950 Population Registration Act were given the designations “Black”, “Coloured”, “Indian” and “White” – now fighting against a common white oppressive system.

The Freedom Charter and 1996 Constitution

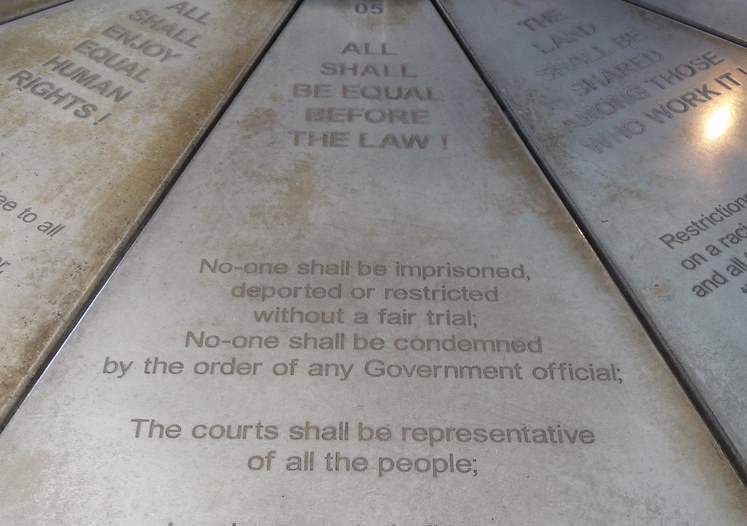

This nationalism and, we could say, the populist activities it engendered was clearly articulated in the opening lines of the 1955 Freedom Charter. The Charter was the result of an invitation by the ANC to the whole country to write down their demands for the kind of South Africa they wished to live in. Committees were formed in villages and townships, as well as larger cities and towns, and public meetings were called to hear the grievances of the people and to decide what should be included in the charter.

Thousands of demands came in, written on strips of paper, pieces of cardboard, envelopes, cigarette boxes, and school exercise books. This decentralised people-driven “parliament” recording everything that touched people’s lives from education, employment, shelter, freedom of speech and movement, began with the words:

We, the People of South Africa declare for all our country and the world to know: that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white […] that only a democratic state, based on the will of all the people, can secure to all their birthright without distinction of colour, race, sex or belief.

If we consider the definition of populism as a politics which appeals to the everyday ordinary people living lives they feel are being supressed by an established elite, then the Freedom Charter is a populist call, a text produced by a populist politics. Our current Constitution can also be considered, in this sense, a populist text, it being clearly inspired by the Freedom Charter.

Its preamble states:

We, the people of South Africa, Recognise the injustices of our past; Honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land; Respect those who have worked to build and develop our country; and Believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.

Our Constitution was adopted in 1996 and the ANC, the people’s party, has governed our country for the last 27 years (the same number of years that Mandela was imprisoned).

The past in the present

In the meantime, I attended an all-girls Anglican school in the leafy suburbs of Cape Town and now my concern was for my dad to buy me a pair of Nike Cortez like everybody else. However, the racial classifications of the past were not dissolved and continued to reflect the inequality of South Africans’ relations with each other. In my school, and sticking with these classifications to illustrate the point, there were eight Coloured girls, four black girls, and 85 white girls in my year. Did I mention that South Africa is made up of 75% black people, about 10% Coloured people and 10% white people? At 15 years old, I did not think anything of never really interacting, never really seeing, people who were not my own race.

Today, our social and economic situation seems years away from realising many of the demands of the Freedom Charter and the 1996 Constitution. The rift between the identities or nationalism of white people and those of black people remains largely unbridged, or at least there exists only a very rickety one, slowly and in some places building stronger foundations. But it seems that only very few people are willing to cross it. We are a country of hope, but the economic inequality and continued racial separation remain despairing. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, this fact and its historical embedding is being used by politicians to gain political ground. Which, in turn, widens the rift.

One or two examples can illustrate this point. On the stage of our inglorious political theatre, we have Julius Malema, leader of the Economic Freedom Front, a party with socialist ideologies and self-proclaimed representative of “we, the people”. Malema calls for the nationalisation of banks, expropriation of land without compensation, and ridding of university fees. His tag line is fighting Apartheid and colonialism, often merging both, and he has been described as a fascist populist. In 2011, he was found guilty of hate speech for singing the controversial struggle song, “Shoot the Boer” (Boer referring to the Afrikaner). In another of his most contentious moments, he said:

When whites arrived in South Africa, they had committed “a black genocide” when blacks were dispossessed of their land. They found peaceful Africans here. They killed them. They slaughtered them like animals. We are not calling for the slaughtering of white people, at least for now.

“We are not calling for the slaughtering of white people, at least for now.” Malema, Ezra Claymore, The South African, 8 November 2016.

We have another example with the Democratic Alliance, main opposition to the ANC and, although is led by a black man, remains the “white party”. Helen Zille was a former leader of the DA, and until 2019 she was premier of the Western Cape province. In 2017 she tweeted the following:

For those claiming legacy of colonialism was ONLY negative, think of our independent judiciary, transport infrastructure, piped water etc.

— Helen Zille (@helenzille) March 16, 2017

In a second tweet, she said:

Would we have had a transition into specialised health care and medication without colonial influence? Just be honest, please.

— Helen Zille (@helenzille) March 16, 2017

What happened after that was nothing less than mass outrage. The backlash started five minutes later on Twitter, with Zille accused in various ways of being racist and insensitive, one tweet parodying her comment, saying:

#Hitler built #AutoBahn. #Mussolini made trains arrive punctually. And an “independent” #Apartheid judiciary sent #Mandela to jail #Slowclap https://t.co/QsWlZ0aNYg

— Nickolaus Bauer (@NickolausBauer) March 16, 2017

But equally people gave arguments for the legacy of colonialism and against current policies as being racist towards white people. That is to say, there are many sides of the coin. Never is an extreme view, or even a singular view, the right one and especially not in a country which is so visibly diverse. What happens in these political debates is that the racial tensions that still exist in South Africa find an effective medium in which to explode anew. Zille was ultimately suspended from the party and from all DA activities while a disciplinary hearing went under way, and finally found by the Public Prosecutor to have violated both the Executive Members Ethics Code and the Constitution.

What is the role of the legal historian?

Although these examples have been overtaken by new scandals and new stories on the South African political stage, the broader point is that the historical accuracy of Zille and Malema’s statements are not what politics in South Africa is about. Our country is still so attached and implicated by our racial identities. As am I. After school, university, a year abroad, I always took my identity as a white South African with me; it gave me a sense of status. That identity generally meant I was not poor or uneducated. It meant that I lived in a house, not a shack in a township, that my language was the spoken language and I could speak without effort or resistance. I was different from the majority, so I was separate from the rest, maybe even special. Better? Certainly economically. Morally, ethically? Far from it. But at the time, I didn’t think (or preferred not to think) too much about it.

Then I moved to Johannesburg and for the first time my eyes were opened to the “real” South Africa. Joburg is an amazing place and I would recommend everyone to spend time there. I worked with people from many different backgrounds for the first time. My black colleagues were so empowered, they spoke up and about things that I hadn’t even noticed, that I had chosen not to see. And in Joburg you are exposed every day and much more viscerally to the other side. It is an ugly city founded on gold mining and hard work, beggars stand at every traffic light, Alexandra township is within two kilometres of the most expensive square mile in Africa: Sandton. From Alex, Sandton looks like a kind of unreachable utopia.

So, what is the role of the legal historian in this context? Honestly, I don’t know. Again, the often hot-blooded conversations between politicians and the people, between black and white, is not remedied or even improved by clarity of historical facts. I don’t think it should even be on our agenda to go about correcting these claims or arguments, to detail the whole picture of our past.

Many white people feel guilty, others are in denial. Other white people and black people – and Asian, Coloured, Indian, Muslim, Christian, Jewish and Hindu people – are scared for the future. A generation of white Afrikaners are in an identity crisis, asking: are we the same as our parents and grandparents? Black people are angry and hurt but more and more they are also empowered. The Coloured community has been considered somehow lost, totally removed from the conversation, being too black under Apartheid and too white now.

The point is that we, the people are still in a state of feeling the past, not analysing it. South Africans need some kind of catharsis. Whether the legal historian can contribute towards that is actually the question.

Cite as: Woods, Alexandra: The black and white facts of the past. A personal perspective on how legal history plays a role in South African politics, legalhistoryinsights.com, 23.09.2021, https://doi.org/10.17176/20210923-164246-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a