Some will have noticed: the Max Planck Institute for European Legal History has changed its name at the beginning of 2021. The reason was the establishment of a third department for legal theory – hence the expansion of the name to include this subject. But why did we delete the word “European”?

The reason is not that we no longer deal with legal histories in Europe or even with the question of whether there are actually certain European particularities. On the contrary, a large project on the legal history of European integration is being carried out in the department “European and Comparative Legal History“, and many individual projects in all three departments also continue to deal with legal histories and legal theory in Europe.

European legal history of the post-war period

When we do European legal history today, however, we do it differently in some respects than it was done in 1964 when the Max Planck Institute for European Legal History was founded. The founding director Helmut Coing (centre), but also the first chairman of the institute’s board of trustees, the former president of the EEC Commission, Walter Hallstein (right), namely had a clear idea of what “European” meant.

At that time, people still thought differently about Europe’s position in the world, not least about how the present was shaped by history. And they had different ideas about how to write legal history. Helmut Coing opened the Institute’s first journal, Ius Commune, with an essay on European legal history as a unified field of research, in which he gave expression to this idea.

This has since been historicised, criticised and discussed. Indeed, from today’s perspective, many of these ideas of a European legal history are Eurocentric and methodologically inadequate. Nevertheless, there is of course an incredible amount to learn from the research of this generation, and it has rightly been said that European legal history is ultimately still a project. To this day, we write national legal histories that largely stand unconnected next to each other, and Europe is mostly seen as a self-contained global region.

De-Europeanisation of legal history

The generation that grew up in the “Berlin Republic” and thus in times of transnationalisation of law and the study of law, but also of debates on postmodernism and postcolonial perspectives, must see this differently. They have a different approach to European legal history.

It is the task of the Max Planck Society to work in a complementary way to the research carried out at the universities and, above all, to develop new perspectives that perhaps do not fit easily into the structures of the universities, which are dominated by teaching. Therefore, it seemed obvious – on the occasion of a new appointment to the post of director – to attempt the project of opening up and de-Europeanising European legal history. How can European legal history be researched from a global historical perspective, as this venture can also be understood? How can one understand the position of Europe and its rights in the world without remaining in the old diffusionist perspectives? What did the colonial and imperial past actually mean for Europe and its legal histories?

Global Legal History

Despite the many open questions as to what global legal history actually is, such a new perspective on European legal history requires, not least, a good knowledge of legal histories other than those of Europe. In addition to methodological reflection, it also requires intensive cooperation with researchers in other regions of the world. For global legal history is only good if it is also excellent local legal history. It needs other concepts and must be open to other academic practices.

In the last ten years, the Max Planck Institute has therefore increasingly turned its attention to legal histories beyond Europe. It began with research projects on the early modern Spanish empire, primarily in Europe and Latin America, and now also in Asia. We subsequently learned more and more about the Portuguese monarchy and its expansion into America, Africa and Asia. In the meantime, we speak of “Iberian Worlds“, for whose global legal history we have also established our own new publication series. No longer just “law”, but a wide variety of norms, especially from the field of religion, and normative practices became the subject of our work, which we now carry out under the equally new departmental name “Historical Regimes of Normativity“.

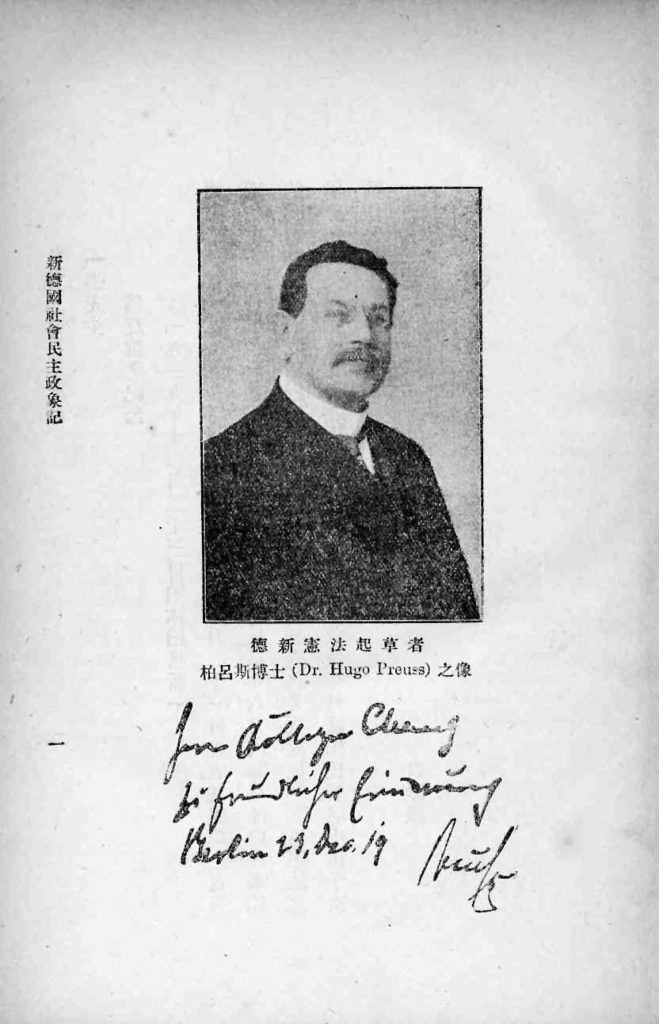

In contrast to the Eurocentric narratives of the spread of European law in the world, we therefore ask about translations, about the processes of “glocalisation” of normative knowledge. How did one understand and into what cultural logics did one translate what one read in Hugo Preuss, for example, and wanted to use for the Chinese constitution? – To understand this, one certainly needs to know something about Weimar constitutional law, but above all about Chinese legal history and the impact of Western thought.

Zhang, Junmai 张君劢 (1922), Xin Deguo Shehui Minzhu Zhengxiang Ji新德国社会民主政象 aus: [Comments on Social Democracy of New Germany], Shanghai: Commercial Press 商务印书馆

With the establishment of the Department of European and Comparative Legal History under the direction of Stefan Vogenauer in 2015, long-awaited research on the history of common law and the transfer of law in the British Empire could now be carried out at the Institute. Scholars with knowledge of Asian languages and research groups focusing on a comparison of legal practices, such as Translations and Transitions, expanded the Institute’s fields of work even more. In April 2021, another Max Planck research group on the history of international law in colonial Africa began its work at the Institute. And in 2022 yet another research group continuing with the work of the Global Legal History on the Ground project on a larger scale will be established.

What is in a name?

The name of an academic institution is of course more than just a designation. It is often a programme, as in the case of the name Max Planck Institute for “European” Legal History. The deletion of this addition has therefore certainly irritated some people. That is understandable, and perhaps it is even necessary. But the reason should become understandable in view of the changes in our fields of research. But there is no cause for concern: the “Studies in European Legal History“, as our oldest publication series at Klostermann-Verlag is called, will of course continue, even if new perspectives such as the “Global Perspectives on Legal History“, which we inaugurated a few years ago, have taken their place.

The name change is therefore important, but it should also not be seen too dramatically. Just as, incidentally, the addition of “European” was only added to the name at the last minute in the course of its founding, and above all at the request of the universities, in order to ensure a clearer distinction from university research institutes for legal history, in our case, too, there is finally a very practical reason: a “Max Planck Institute for European Legal History and Theory” would not only no longer express what we do. The name would also simply be too long. It also has to fit on the façade.

Cite as: Duve, Thomas: What about “Europe”?, legalhistoryinsights.com, 26.06.2021, https://doi.org/10.17176/20210628-143858-0