This is the story of the cannon as a tool to delimit maritime space in the history of the law of the sea. It is a story that spans from the 17th to the 20th century – it is a story about a state practice that became legal theory, technological progress and Western dominance in international law.

From Practice to Theory: The Admiralty and the Jurists

The cannon-shot rule is said to have been first mentioned by the Dutch delegation at the London Fisheries Conference in 1610. In May of 1609, King James I had issued a proclamation prohibiting ‘strangers’ from fishing in waters claimed as British seas. The underlying consideration of the Netherlands was therefore to find an argument that would allow their seamen to continue to sail to the fishing grounds as unrestricted as possible. Against this background, the Dutch delegation in London thus claimed that:

For that it is by the law of nations, no Prince can challenge further into the sea than he can command with a cannon except gulfs within their land from one point to another.

(Transcription of the facsimile provided by Fulton, p. 156.)

The author of this formulation is not known. In 1625 however, Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) took a somewhat similar position in his work ‘De jure belli ac pacis‘. Arguing that people who sail close to shore can be kept from it by force from land (see bk. 2, chap. III, §13.2). Although one may doubt that this statement is sufficient evidence of Grotius authorship of the cannon-shot rule, it seems somehow fitting that a number of past and eminent historians of international law would like to attribute it to one of their father figures.

While Grotius remains controversial as the originator of the cannon-shot rule, the person who popularized it in the literature of international law and has since been considered its most important reference point is well known. Cornelius van Bynkershoek (1673–1713), like Grotius a Dutchman, published his dissertation on the questions of state claims to the sea in 1703. From the beginning to the middle of the 17th century, the so-called battle of the books had been waged, but had during Bynkershoek’s lifetime already come to an end. This battle of ideas about the sea as a legal space, whose main protagonists where Hugo Grotius and the English jurist John Selden (1584–1654), was a highly theoretical one. On the question, what degree of state control over the sea is sufficient to claim sovereign rights, Bynkershoek had a much clearer and more practical answer than his predecessors involved in the dispute. Grotius and Selden, but also today lesser-known jurists like Seraphim de Freitas (1570/72–1633) and William Wellwood (1550/52–1622) based their arguments mainly on rather complex religious, philosophical and historical sources. Bynkershoek, in contrast, argued in his book ‘De dominio maris dissertatio‘ (1703) from the perspective of effectiveness in relation to state authority over the sea. First, he criticized the existing practice of delimiting maritime space by sight as too vague to be utilized. Bynkershoek wrote:

And yet this seems to be also the way it is defined by Philip II, King of the Spains, in the Nautical Laws, which he gave to the Netherlanders on the last day of October, 1563; for there foreigners are forbidden to attack their enemies within sight of the land. It is settled, therefore, that the subject sea extends that far. But this also is too loose and variable a rule, or at any rate it is not very definite. For does he mean the longest possible distance a man can see from the land, and that from any land whatever, from a shore, from a citadel, from a city? As far as a man can see with the naked eye? or with the recently invented telescope? As far as the ordinary man can see, or he that has sharp eye-sight? Surely not as far as the keenest of sight can see, for in the ancient writers we are told of people who could see all the way from Sicily to Carthage. And so this rule also is wavering and indefinite.

(Translation by Magoffin, p. 44.)

Bynkershoek therefore went on to describe his thoughts for a more appropriate approach of maritime delimitation.

Wherefore on the whole it seems a better rule that the control of the land (over the sea) extends as far as cannon will carry (quousque termenta exploduntur); for this is as far as we seem to have both command and possession. I am speaking, however, of our times, in which we use these engines of war; otherwise I should have to say in general terms that the control from the lands ends where the power of men’s weapons ends (potestatem terrace finiri ubi finitur armorum vis); for it is this, as we have said, that guarantees possession. […]

(Translation by Magoffin, p. 44.)

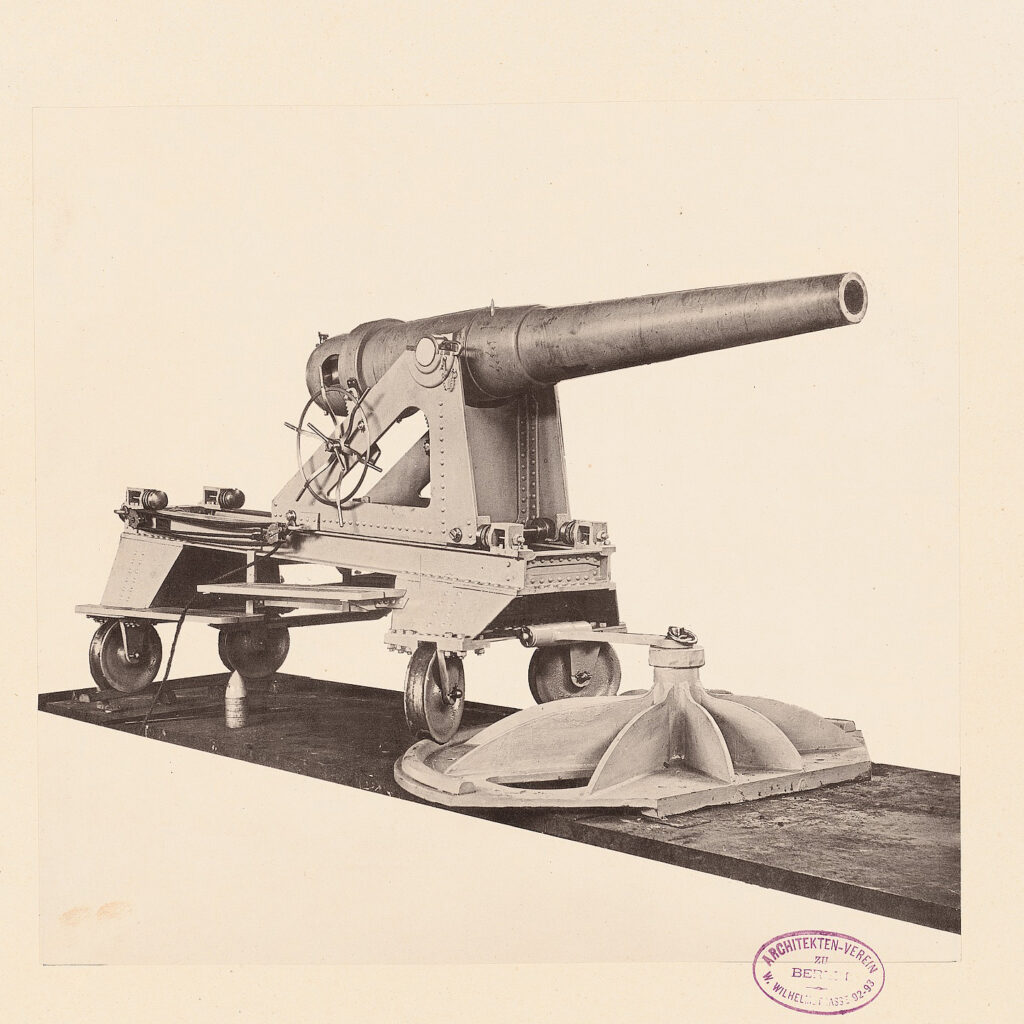

Although Bynkershoek did not actually invent the cannon-shot rule, he adopted a state practice and made it international legal theory by importing it into his treatise. According to Sayre A. Swarztrauber, the French admiralty treated the cannon shot as established practice in matters of capture at sea at least since 1685. In concrete terms, this meant that acts of war between other parties were not permitted in the protected waters within the range of French cannons stationed on the coast. Another notable state that engaged in a similar practice of the cannon shot in order to guarantee neutral waters was Bynkershoek’s homeland, the Netherlands. In essence, however, the idea of effectiveness meant: no cannons on the ground, no sovereign rights respectively no protection for the purpose of neutrality.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art

While the line-of-sight doctrine indeed started to loose its appeal after the publication of the ‘De dominio maris dissertatio’, another state practice nevertheless persisted alongside the cannon-shot rule that was now becoming increasingly prevalent in Europe. In contrast to Bynkershoek’s idea, Denmark, Norway and Sweden, claimed that their neutrality was guaranteed by a continuous belt that extended into the sea, not merely by zones protected by cannons on the ground. Although the two ideas were distinct in nature (effectiveness vs. abstractness) at the beginning of the 18th century, they increasingly began to merge over time. The result was the idea of a general three-mile limit – the assumed median range of cannons at the time – for the territorial sea. For Wyndham Walker, however, the historical identification of cannon range with the three-mile limit is not entirely convincing, asking whether it might have been more ‘a fiction of eighteenth-century jurists striving to combine, reconcile and explain divergent practices, and to secure for the future a more practical working rule’ (p. 231)? In any case, the development was not to remain without consequences over the next two centuries.

Projecting Power: The Costa Rica Packet Arbitration and the Riau-Lingga Archipelago

Leaving the 18th century and the geographical region of Europe, we now travel to Asia at the end of the 19th and early 20th century. Two events took place here that are relevant for our story of the cannon-shot rule. First, the 1891 detainment of the captain of the whaling ship Costa Rica Packet and subsequent arbitration taking place between the Netherlands and Great Briton. Second, the 1902 decision by the Dutch Minister of Colonies not to grant self-governing territories their own right to a territorial sea.

The crew on board the Costa Rica Packet, ca. 1890 © National Libarary of Australia

During the whaling season, 1887–1888 the Costa Rica Packet sailed under the command of Captain John B. Carpenter in the Moluccas Seas. The British-flagged ship, registered in Sydney (New South Wales), encountered an abandoned Malian boat (prauw) in January 1888. On the orders of their captain, the crew took the cargo stored on the prauw – some of them with the logo of a local company – on board their own ship. However, they later threw most of the goods back into the sea because of their already poor condition. What little they kept, they sold some time later in a nearby port. In November 1891, during a stay of the Costa Rica Packet in Ternate, Carpenter was arrested by the Dutch authorities. They accused him of stealing from the prauw in their territorial waters and held him captive for about a month. After Carpenter’s release, the British government subsequently demanded compensation from the Netherlands for Carpenter’s internment, the loss of income of the crew as well as the ship-owners. The Dutch rejected this demand, but ultimately accepted the British proposal for international arbitration. Again, after some setbacks, it was agreed that the arbitration should take place through the court of the Czar of Russia. In January 1895, the court appointed Frederic de Martens (1845–1909) a Russian professor, diplomat member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Already in 1894 Martens had pleaded for an increase of the territorial sea to ten miles in accord with the mean range of modern cannons. In Martens opinion, only this would ensure the effective protection of the interests of the adjacent population, which lives from fishing. Although he ultimately ruled that the Costa Rica Packet had not been in Dutch territorial waters and therefore within its jurisdiction, the idea to adapt the cannon-shot rule to the actual range of fire echoed in the reception. In 1913, Arnold Ræstad (1878–1945), one of Norway’s former experts on the law of the sea, stated that the cannon-shot rule had by this time nearly become an axiom. However, worrying about the opinion of some, ‘that the nations might, if they wished, and even ought to, adopt the limit of the actual range of modern cannon except in relations regulated by international conventions’ (p. 401). In 1928, Thomas Baty sharply criticized Martens approach of increasing the breadth of the territorial sea to the actual cannon range of his time, noting, ‘it is significant that he (Martens) was a Russian official’ (p. 504).

In the same region, only a few years after the Costa Rica Packet arbitration took place, another event occurred that related to the cannon-shot rule. This time, however, it was less about the technical advancement of cannons and their increased range, but rather concerned the fundamental idea of being able to project power seaward. As John G. Butcher and R. E. Elson describe in greater detail in their book based on work in the Archive of the Ministry of Colonies, the Dutch colonial minister decided in 1902 to deny self-governing territories a right to sovereignty of coastal waters. According to Butcher and Elson, the question began to arise for the Dutch, when foreign companies in particular began to exploit the resources in the waters around the Aru Islands and the Riau-Lingga Archipelago. An investigation by the Dutch colonial administration revealed that local chiefs in the region claimed jurisdiction over the sea similar to the concept of territorial waters. This presented the Dutch colonial administration with the problem of possibly losing control over these maritime areas if the rights of the local population were to be recognized. To find a solution, the secretary-general of the minister turned to a book stored at the Law Faculty of Leyden University. In ‘Das Völkerrecht – Systematisch dargestellt‘ (first ed. 1898), the German jurist Franz von Liszt (1851-1919) argued that international law was the product of negotiation between civilized, Christian states. Non-European political entities could join this system only if, first, they appropriated these characteristics and, second, if a European state acted as an intermediary, for example, as their colonial overlord (see p. 1–5; p. 47–48). Moreover, he took the position in accordance with the Dutch line regarding territorial waters:

Küstengewässer nennt man denjenigen Teil der offenen See, den der Uferstaat durch Strandbatterien von der Küste (sei es des Festlandes, sei es der Inseln) aus zu beherrschen vermag. Die Bestimmung der Grenzlinie der Küstengewässer ist sehr bestritten (p. 51).

According to Butcher and Elson, the secretary-general read Liszt’s position as follows: ‘that if native states had any jurisdiction over the waters adjacent to their land territories it extended no further than it was possible to throw a stone or shoot an arrow since, so he (the secretary-general) seems to have assumed, these states had no means of projecting their power any further out to sea’ (p. 16). Based on Liszt’s argumentation and the advice by his secretary-general, the minister for Colonial Affairs eventually decided to deny the self-governing realms the possibility of claiming sovereignty over parts of the sea on their own. Only the Netherlands was able to establish territorial waters because the concept was of European origin and, inter alia, it had the technical/military means to do so.

Rest at Shore: The Cannon as a Witness of International Legal History

The short story that have been told here was about a state practice that originated in Europe and became international legal theory. The practice of using cannons to delimit protective zones for the purpose of neutrality, which had been practiced since the mid-17th century, eventually became a legal theory through Bynkershoek’s treatise. The regulation seems to have been attractive to other states because of its distinct possibility of application. However, primarily the Scandinavian states continued a practice of delimiting a continuous belt of neutrality at sea. During the 18th century, both practices started to merge due to jurists who thought to reconcile the diverting approaches. The idea of neutrality increasingly receded into the background and was replaced by that of sovereign rights guaranteed by potential for the use of force by cannons theoretically stationed on the coast. This had consequences for indigenous societies, who were denied a right to territorial waters due to a lack of military technology. Additionally technological progress rapidly increased the range of cannons over time, and a dispute arose in the 19th and 20th century as to what effect this should have on the enlargement of territorial waters. Even after 1958, the state practice of delimiting territorial waters continued to vary, and the cannon-shot rule was still mentioned at the first United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea. It was only through the negotiations (1973–1982) on the so-called Constitution of the Oceans that, in a mammoth diplomatic achievement, maritime zones have become uniformly defined. Since the entry into force of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) with its fiftieth ratification in 1994, the underlying idea of the cannon as a tool for delimiting maritime space was finally put to rest. Nevertheless, disputes over the claiming of maritime zones continue to arise and persist. This is exemplified not only by the current disputes between Greece and Turkey in the Mediterranean, the ongoing conflict in the South China Sea, but also, for example, the unclear legal status of waters in the Arctic.

Meanwhile, the old cannons have lost their former purposes and are technologically obsolete; now resting on the seacoasts of the world. To a visitor they are not only witnesses of bygone military strength, but also an object of international legal history.

Cite as: Pogies, Christian: The Canon. A Tool for Deliminating Maritime Space; legalhistoryinsights.com, 14.06.2021, https://doi.org/10.17176/20210628-141151-0