The Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory (mpilhlt) has recently approved its Research Data Policy. In accordance with this document, our institute commits to systematic management of research data in line with established standards and best practices, thus assuring the quality of research, satisfying legal and ethical requirements and contributing to the responsible handling of resources.

The Love Your Data blog series is your easy guide into the world of research data management (RDM). In this post we will look at the important legal aspects of your data, mainly those which define what you may and may not do with it: copyright and licences. These are the aspects that every researcher should be aware of to better understand their data and plan its handling more effectively, especially when publishing their own data, or reusing data from others.

Read Part 1 “What is Research Data Management and Why it Matters” here

Read Part 2 “A Researcher’s Guide to the Data Life Cycle” here

Read Part 3 “From Metadata to FAIR Principles: Make Your Data Better Now” here

How (not) to Read This Guide

What I am going to present here is a set of general and very practical guidelines written by a researcher (with a training in RDM) for a fellow researcher. These guidelines are in no way meant to be exhaustive, as I will solely focus on the aspects relevant for legal history and omit aspects that are not so important for our discipline. Please take note that these guidelines are general, and there may be additional individual factors of your research data that are not accounted for here. This blog post aims to give you a broad orientation, but please always observe each data use case individually.

As Open as Possible, as Closed as Necessary: What can Restrict Your Data Use

In the previous posts (here and here), I already mentioned the RDM principle, “As open as possible, as closed as necessary”, it is not always possible to publish our data as open access, or share it with our colleagues even if we want to. There may be different legal and ethical reasons for this. One of them is the issue of copyright and licences, which define how research data may be used and what restrictions there are.

Is Copyright Applicable to Research Data?

Copyright in science protects the rights of the researchers to their original work, be it a scientific paper, a book or some other kind of research output. But what about research data? Is it usually a subject to copyright? Is there such a thing as “my” research data? The short answer is no: in the German legal landscape, data is generally not a subject to copyright and there is no concept of data ownership as such (Kuschel, 2018). However, under some circumstances, research data can fall under copyright protection. Before we take a closer look at these special requirements, let’s not forget that copyright protects only the form of a work, but not its contents. That means that under certain circumstances the form of research data, i.e. its concrete representation: be it a text; a table; an annotation; or something else, can be subject to copyright, while the information, facts, and ideas the data contains are not (Kreutzer & Lahmann, 2021).

As a rule, the dataset should reach a minimum threshold of creativity and be a result of a personal intellectual creation to be copyrightable. Raw data (unprocessed data from a primary source) in its original, unprocessed form is not copyrightable. That means, for example, that any data created automatically by computer or software without any creative human input will not be copyrightable. For this reason, data should have some degree of creativity and be a result of the intellectual human work to enjoy copyright protection.

Concrete Applications from Legal History

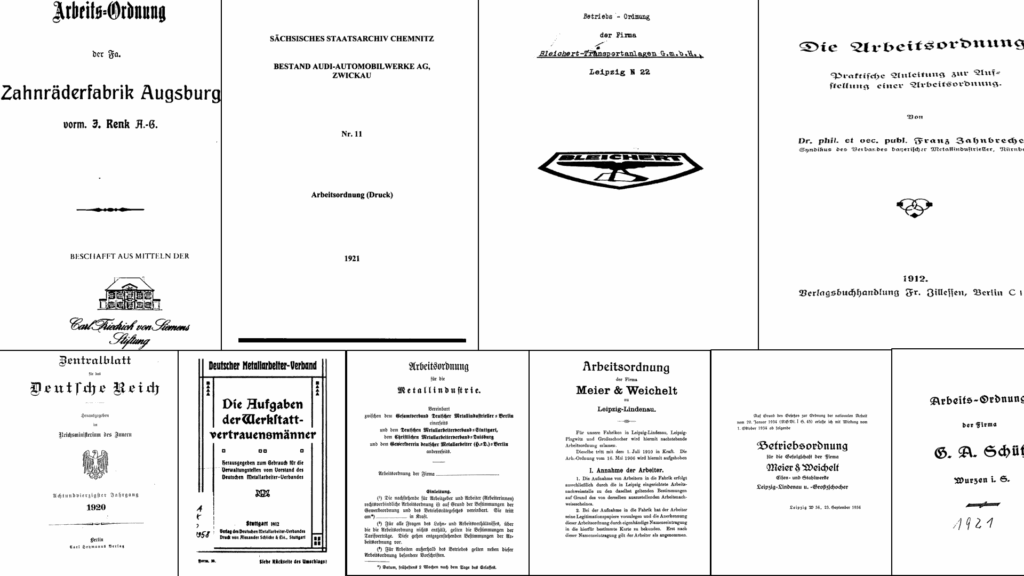

The minimum degree of creativity or individuality is not defined concretely (Kreutzer & Lahmann, 2021), but, for example, non-creative texts like Arbeitsordnungen (work regulations) from the Non-State Law of Economy project would not be considered a subject to copyright, as they often follow a model work regulation (Muster-Arbeitsordnung) and generally have fixed structure expressed in a similar language, although some variations are, of course, possible.

So, what does it mean for us in practice? Let’s continue with the example of the Non-State Law project: if we go to an archive and take a photo of the documents there, and then transcribe the documents with some automatic transcription tool like OCR4all or Transkribus, the transcripts that we get from the tool (even if we correct some mistakes that the automatic transcription tool produced) do not fall under copyright protection, as they are still raw data – texts automatically extracted by a machine from the source. The same applies to the digital images of the original archival documents: the fact that we did the digitisation of the original documents and created their digital images does not grant us copyright over the reproduced facsimiles. If the archival documents we digitised were in public domain, as is the case with documents from Non-State Law project (remember they do not reach the minimum threshold of creativity to enjoy copyright), then the images we produced would be in public domain too. However, if the archival documents happened to be under copyright, one would not be allowed to share or publish any digital copies of the original material without permission from the copyright holder.

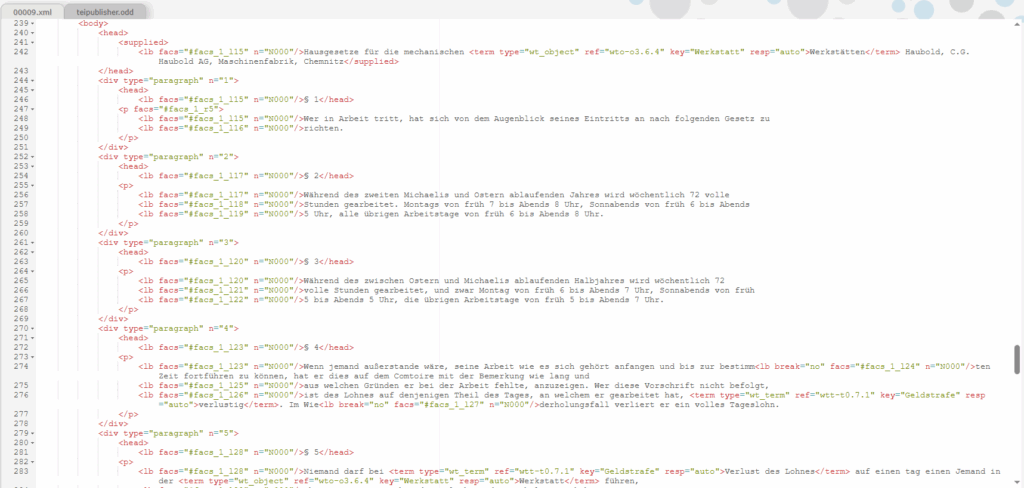

If we take these transcripts and start to annotate them with TEI XML markup, giving them a certain structure, interpreting and enriching them with annotations and working on them manually, then they will most likely reach the required degree of individuality and creativity to be copyrighted, and then us researchers as the copyright holders could choose how to share this data, what licence to choose and so on.

Public Domain Data

If the data is free from copyright restrictions (either because it is not subject to copyright or is no longer under copyright, which in Germany is limited to 70 years after the author’s death), it should be released back into the public domain under a CC0 licence, which means that there is no copyright over this data and anyone can use it as they wish with no restrictions. Publishing your data under CC0 puts it in the public domain, but you can still get a DOI for your data and be credited for your work. Even though there is no formal obligation to cite your work when reusing your data, good scientific practice requires giving due credit to the data’s original authors. It is not recommended to use other licences for the data that is not subject to copyright, even though in science it is often done, probably due to researchers not wishing to lose the idea of control over how their data is reused (Hartmann, 2022).

Choosing Licence for Your Data/ Understanding the Terms of Use of Other’s Data

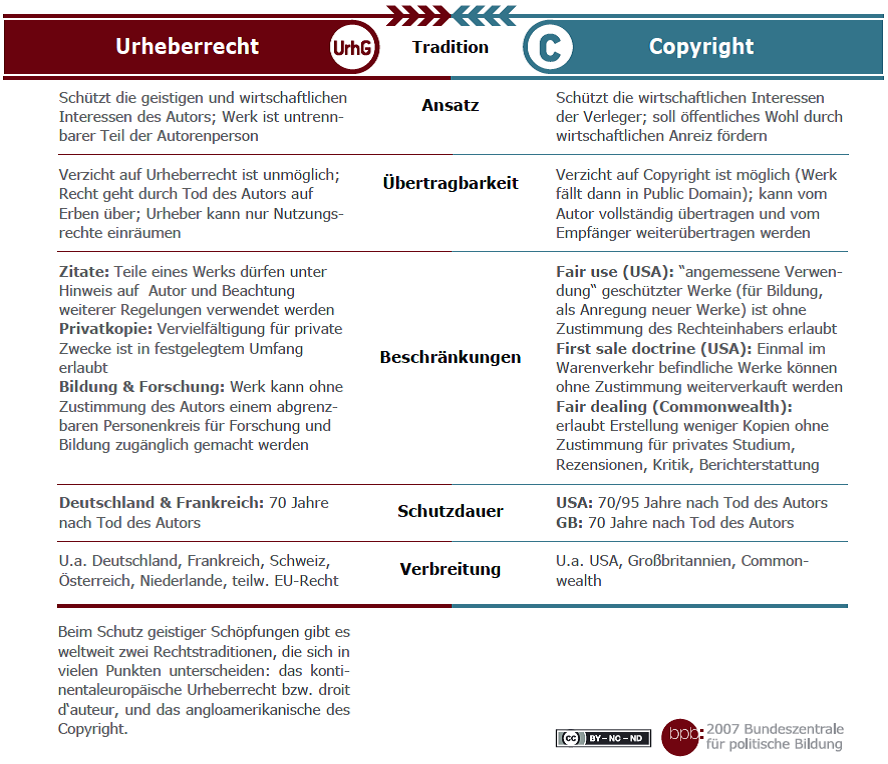

If you want to reuse some data produced by others, please always check what licence/ terms of use it has. A licence will help you to understand what you may (not) do with data. Version 4.0 of the Creative Commons Licence is a standard for scientific publications and can be used for research data publications as well. The licences vary in degree of openness and good explanations of what particular Creative Commons licences mean in practice can be found here. There is even an automatic tool that can help you decide what licence is best for you. For your own data, it is always recommended to choose CC BY 4.0 or CC0 (for non-copyrightable work or if you want to waive your copyright), as any other more restrictive licences like non-commercial (NC) use only or share-alike (SA), can prevent reuse of research data by other scholars. For example, if I wanted to give you an overview of the difference between the concepts of Urheberrecht in Europe and copyright in Great Britain and the USA and tried to reuse this digital image for this purpose, I would not be allowed to translate this image into English:

This image is distributed under CC BY-NC-ND licence, where ND stands for no derivatives and means that no remixing, transformation or building upon is allowed and under CC licences translation is explicitly considered to be an adaptation.

The same goes for NC (non-commercial) restrictions: even though it is often applied in science with best intentions at heart, it can have unaccounted adverse effects in hindering reuse, as it can be challenging and sometimes blurry to define what represents commercial (re)use (Lauber-Rönsberg, 2021).

Usage Rights for Archival Material

Use regulations of material obtained in an archive can differ drastically from one archive to the other. Before going on an archival trip, it is advisable to first think about what you would like to do with the documents you encounter in an archive (and maybe also what you are allowed to do with them based on their copyright status). If you just want to read them and take some handwritten notes, you are probably on the safe side and no additional permission is needed. But if you want to take pictures, then it gets more complicated: are you allowed to take pictures yourself? Or does an archive only allow commissioning pictures through them? May you use a ScantTent? Not all archives and libraries allow the use of tripods. And before you get your pictures, you need to think through how you would like to use them afterwards. Would you like to publish the documents’ images? Or maybe use Transkribus and extract and publish the text? Do you plan to share the photos with your colleagues at the institute? All these questions should be considered before your archival trip and checked/ negotiated with archives. Archives may be very reluctant to let their users digitise their documents and share them with others. However, it should not preclude you from attempting to negotiate with them. Getting back to the example of Non-State Law of Economy project, which involved visiting lots of archives in Germany: we had to negotiate and ask for permission from each individual archive on our extensive list and in the end, we were not allowed to publish the images of the documents (for that, one still has to travel to the archive), but we were allowed to publish the digital edition of the texts we extracted from the images (you can read more about challenges of the digitisation of the archival material encountered by our project here) .

Ethical Considerations when Deciding on Sharing “Your” Data

Now that you are aware of copyright, licences, and usage rights for archival material, you can better assess your research data and decide if there are any legal restrictions precluding you from sharing it with others. If there is none, congratulations, I hope you can publish your dataset! But if you are still hesitating, just let me remind you that research data is precious, it is our most valuable currency. Very often, in order to collect it, we have to travel to remote places, spend monetary and natural resources on digitisation and we can count ourselves very lucky should our employers cover the costs and grant us the permission to perform our research. That’s why there is a certain ethical obligation on our part as researchers to share this data with our scholarly community, and pass it on to the world at large. In the end, research data is a treasure not to hoard but to share with others, wouldn’t you agree?

References:

Hartmann, T. (2013). Zur urheberrechtlichen Schutzfähigkeit von Forschungsdaten. InTeR – Zeitschrift zum Innovations- und Technikrecht 1(4), S. 199-202.

Hartmann, T. (2017). Zwang zum Open Access-Publizieren? Der rechtliche Präzedenzfall ist schon da!. LIBREAS. Library Ideas, 32.

Hartmann, T. (2022). Forschungsdaten in den Naturwissenschaften: Eine urheberrechtliche Bestandsaufnahme mit ihren Implikationen für universitäres FDM. In V. Heuveline & N. Bisheh (Hrsg.), E-Science-Tage 2021: Share Your Research Data (S. 183-195). heiBOOKS. https://doi.org/10.11588/heibooks.979.c13728

Kreutzer, T., & Lahmann, H. (2021). Rechtsfragen bei Open Science: Ein Leitfaden. Hamburg University Press. https://doi.org/10.15460/HUP.211

Kuschel, L. (2018). Wem “gehören” Forschungsdaten? Forschung und Lehre.

Lauber-Rönsberg, A. (2018). Sind Beiträge von Hilfskräften schutzfähig? Forschung und Lehre.

Lauber-Rönsberg, A. (2021). 1.4 Rechtliche Aspekte des Forschungsdatenmanagements. In M. Putnings, H. Neuroth & J. Neumann (Ed.), Praxishandbuch Forschungsdatenmanagement (pp. 89-114). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Saur. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110657807-005

Feature image: Server at mpilhlt © Christiane Birr

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a