AI is here. It exploded in popularity last year, came into our phones as downloadable APPs, and now it is creating images. In an article published on March 8, 2024 in The Guardian, Dan Milmo and Alex Hern reported on how Google’s Artificial Intelligence model Gemini was generating images of “popes, founding fathers of the US and, most excruciatingly, German second world war soldiers – as people of colour.” The faux pas led the company’s co-founder Sergey Brin to utter what became the article’s title: “We definitely messed up.”

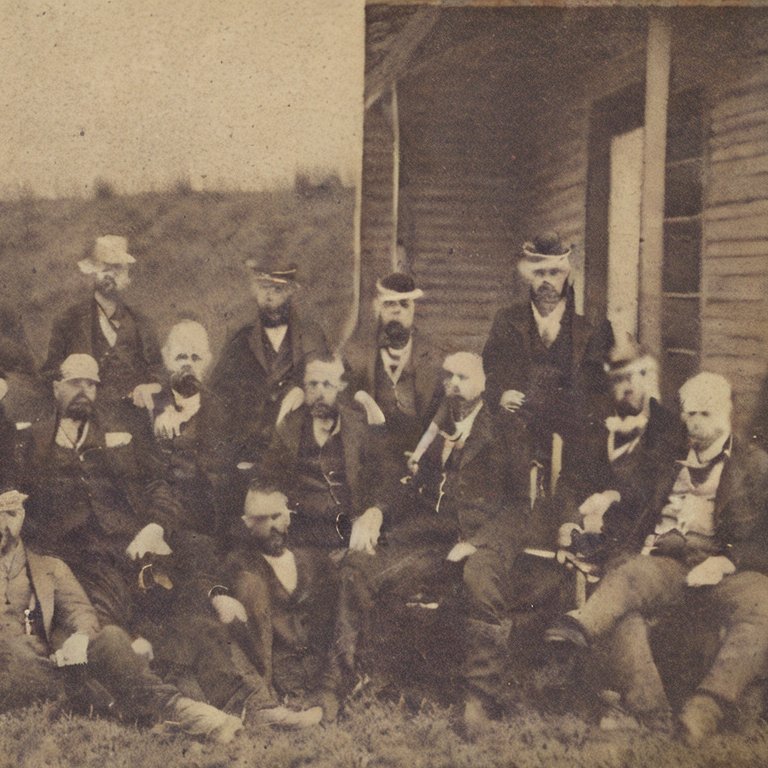

But if pictures of Black Africans fighting on the German side during the Second World War are easy to debunk, the challenge is growing more difficult. Midjourney, an AI model capable of creating complex images based on text prompts, has created photorealistic images able to stump academics. AI-generated pictures mimic textures of old photographic paper, the soft focus of historical cameras, and the damage suffered by pictures after spending decades lost in the deep corners of grandma’s cabinet, making them more and more difficult to distinguish from real historical photographs.

Last year, photographers Shane Balkowitsch and Herbert Ascherman’s aptly titled “Images May Destroy History as We Know” drew attention to the problem by focusing on the difficulty of learning how to live with the reality of these images. More concerning, though, was the tone taken by Marina Amaral, a digital artist specialized in colorizing historical pictures. In a recent blog post, she reminded us of the challenges of living in a world with images that are “no longer tethered to reality but are instead the product of complex algorithms and machine learning.”

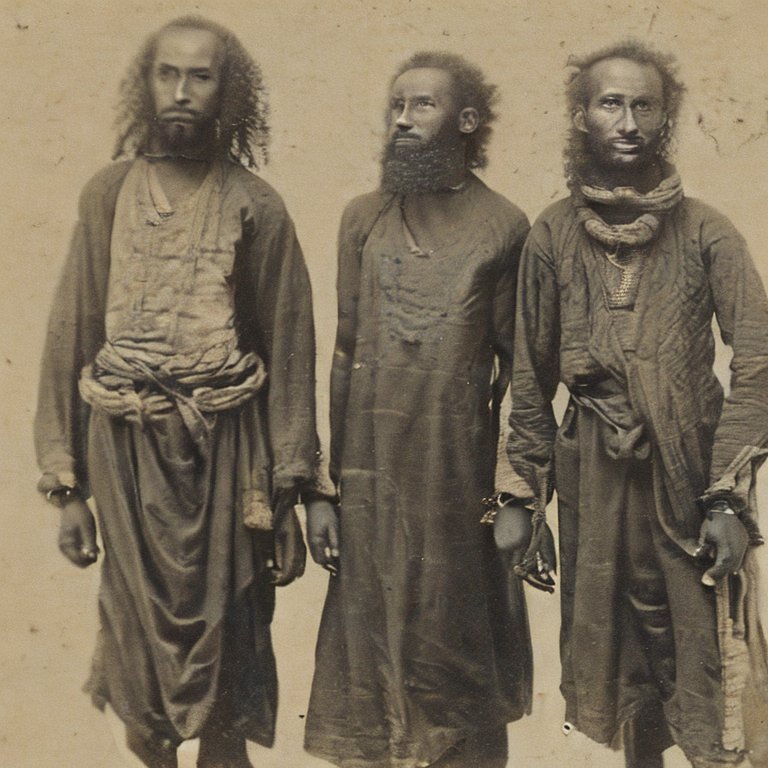

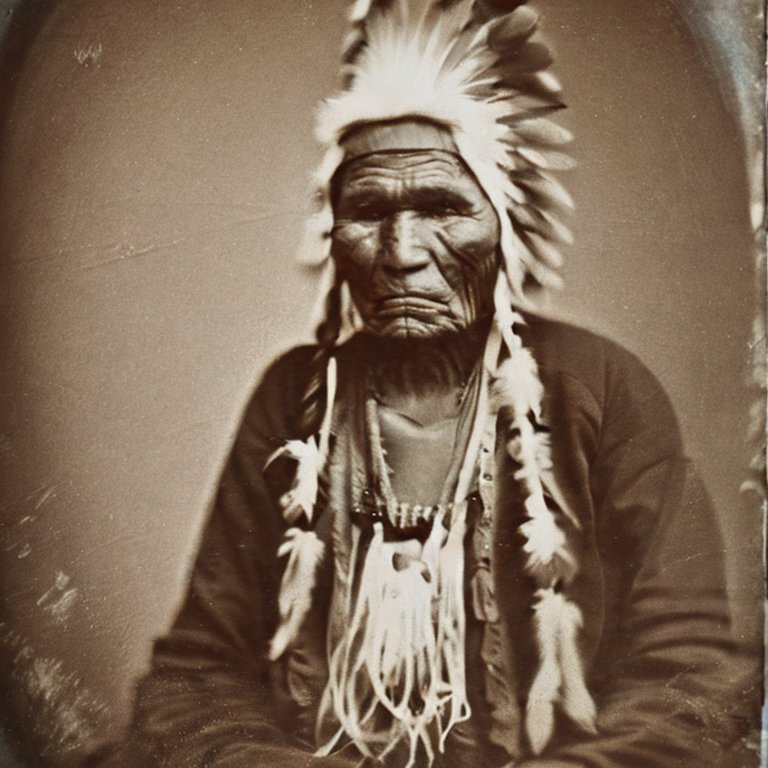

If until now historical images were powerful tools not only for scholars but also for influencing the public perception of our own history, the emergence of AI imagery can represent a huge victory for disinformation. Last October, Victoria Turk wrote a fascinating piece on how AI produces stereotypical images of other peoples: all Indians appear as old men with beards, Mexicans are always men in sombreros, and Nigerian women are never depicted wearing hijabs, despite Muslims making up almost half of the country’s population. Indeed, not only the world is reduced to stereotypes, but to a set of stereotypes held specifically by white Americans and Europeans. Just like Microsoft’s Tay, the 2016 Twitter chatbot that was turned off after a series of racist tirades, AI learns from whatever materials are made available to it.

But how does all of this tie into historical research? Well, if AI is already crafting historical images, how long before it starts churning out historical documents too? Currently, Chat-GPT and similar AI chatbots struggle to produce convincing historical text. Take, for instance, my request to Chat-GPT: “write a Jesuit letter in sixteenth-century Portuguese, written by a priest named Luís Fróis to his colleague, Gaspar Vilela, dated 1582, recounting how he witnessed Oda Nobunaga being killed by his own son during the fire at the Honnoji temple.” Of course, the prompt is ludicrous: Nobunaga’s son wasn’t present in the temple, and Fróis himself was hundreds of kilometers away in Kyushu that night. Besides, Vilela had passed away ten years prior. The resulting text reads more like a modern letter:

My dear Gaspar Vilela,

I hope this letter finds you in good health and spirits. I write to you with heavy heart and trembling hand, for I bear news of a most dire and tragic event that has befallen our beloved Japan.

On the fateful night of June 21st, in the year of our Lord 1582, I found myself in the midst of chaos and flames as Honnoji temple was engulfed in fire. Little did I know that I would bear witness to a moment that will forever stain the pages of history.

Neatly paragraphed, any budding scholar could easily spot the AI’s language as artificial. But how long do we have until that changes?

Certainly, there’s no cause for immediate alarm. The major corporations developing chatbots aren’t exactly racing to teach their large language models—like the ones powering Chat-GPT and similar AI tools—to write historical documents. However, Google has seized data from various sources, including Google Books, to train its AI systems, although specifics have not been made public. Nonetheless, when tasked with writing a Jesuit report akin to the one presented to Chat-GPT, Google’s AI chatbot, Gemini, produced a similarly unrealistic modern letter.

However, both Gemini and Chat-GPT inserted the precise date of Oda Nobunaga’s demise—June 21, 1582—even though that wasn’t part of the original prompt. Moreover, Chat-GPT supplemented the information by accurately identifying Nobunaga’s son as Oda Nobutada, with Gemini providing a vivid account of the fateful night of the Japanese ruler’s death. While enhancing chatbots’ ability to create realistic historical texts may not be a top priority, it’s worth noting that entities like OpenAI and Google, among others, possess all the necessary resources to pursue such endeavors.

Associated with the ability to create historical images, could we soon find earnest scholars fooled by fake historical documents? In Japan, where historical literacy rates have long been robust, most people have some sort of old document at home, some stretching back centuries. Graduate students are even encouraged to go to their grandparents’ attics in search of historical materials. While it may be premature to sound the alarm, the specter of AI-generated historical documents looms ever larger on the horizon. Sooner or later, we will have at our disposal the ability to generate JPGs and PDFs of fake historical sources.

The solution to this issue is to increase our ability to verify information. The EU and other governmental bodies are taking significant strides in regulating AI, such as implementing legal requirements for companies to label or watermark generated images as fake. However, observers alert to the limits of such technology and how it might ultimately fail.

Meanwhile, we, as researchers, can drive initiatives to improve access to archival records. These initiatives could include digital platforms, transcriptions, image databases, and even catalogs, all of which can provide invaluable assistance to both scholars in well-established academic centers and in less-privileged regions. If we think about historical pictures, the number of images produced in the last 150 years since the popularization of photography is limited—even if that is a huge number. The same can be said, to a certain extent, about written documents.

At the same time, there’s a growing need for specialized knowledge to accurately discern historical documents. Despite their extensive experience, most historians lack familiarity with the techniques used in paper and ink production, which are crucial aspects of historical source creation. Projects like Moriwaki Yūki’s Global Migration of Silver and Information Transmission in the 16th and 17th Centuries, funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science from 2018 to 2021, have delved into the complexities of paper production in sixteenth-century Japan using non-invasive particle analysis. This approach has led to the development of a new taxonomy for Jesuit letters in East Asia. Similar endeavors hold promise for enhancing our ability to classify and authenticate genuine historical materials, thereby aiding in the accurate identification of historical documents.

Despite the daunting task ahead, which entails numerous legal, practical, technical, and methodological challenges, ensuring scholars can verify the origins of data used is crucial. Like Lorenzo Valla’s debunking of the Donation of Constantine, we will need all this information to train ourselves in discerning real and fake documents. After all, not all AI-generated images are as easily discernible as pictures depicting people of color as German World War II soldiers.

Cite as: Ehalt, Rômulo da Silva: The Specter of AI-Generated Historical Documents, legalhistoryinsights.com, 02.05.2024, https://doi.org/10.17176/20240506-131118-0