In early February 2025, Singapore’s parliament passed a new law aimed at promoting social cohesion between the various ethnic groups in the city-state’s highly diverse society. The “Maintenance of Racial Harmony Bill”, which targets any form of hatred and enmity between Singapore’s ethnic groups, has been criticised as a law that infringes on Singapore’s constitutional right to freedom of expression. This blog places the bill in the wider context of Singapore’s diversity management strategies. To what extent do these strategies embody diversity as a potential risk rather than trust in the peaceful coexistence of Singaporean citizens from different backgrounds?

Law and “Race”

Although “race” as a biological concept has been almost completely eradicated, it is still significant as a social and legal category in many societies. Roughly put, “race” began as a social concept of oppression in the context of European colonialism, was then referred to as a biological category in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and is now a rather ambivalent social category, visible in regulations aimed at combating racism in societies. Doris Liebscher, in her monograph “Rasse im Recht” (2020), reveals the ambivalence of the use of “race” in anti-discrimination laws, using Article 3 of the German Grundgesetz as an example. This impressive study, which sheds light on German, European and US legislation and jurisprudence, also draws on a rich literature of Critical Race Theory from the US academic context, a literature that aims to expose structural racism in norms and institutions. While these perspectives are Western-centric and hardly applicable to the normative discourse in the state of Singapore, with its distinctive historical, social and cultural context, the question of the extent to which a norm reifies a social phenomenon it is intended to combat will be relevant to the case of Singapore at the end of this blog post.

Singapore’s Independence

Multicultural and multiethnic diversity are key elements of Singapore’s national identity, on which the independent state was founded in 1965. Of course, Singapore’s diversity can be traced further back to its colonial past and beyond. But it is important to understand how essential the multicultural narrative is to the current state and society. Singapore was under British colonial rule from 1819–1945 and occupied by Japan from 1942–1945. After 1945, Singapore remained under British control, but gradually elements of self-government were introduced. In 1963, Singapore declared its independence and became part of Malaysia. This was short-lived due to political and economic disputes with the Malaysian government. In August 1965, Singapore became an independent state, not by choice, as Lee Kuan Jew, Singapore’s leader from 1959–1990, said in an oft-quoted speech in December 1965: “Now, to begin with, we are responsible for our own separate destiny: we are independent. Not that we sought it; but independence was thrust upon us.”

Yes to Multiculturalism – But What Kind?

In the years just before its independence, Singapore was the scene of violent ethnic riots that are still part of the state’s culture of remembrance. The riots were one reason why Lee, in the same speech, set in stone the multicultural narrative:

“[W]e ensure that the progress is spread equally, regardless of race, language, or religion. There will be the same schools for all, the same hospitals for all, the same low-cost housing for all – regardless of whether you are brown, black, yellow, green or any other spectrum of the rainbow.”

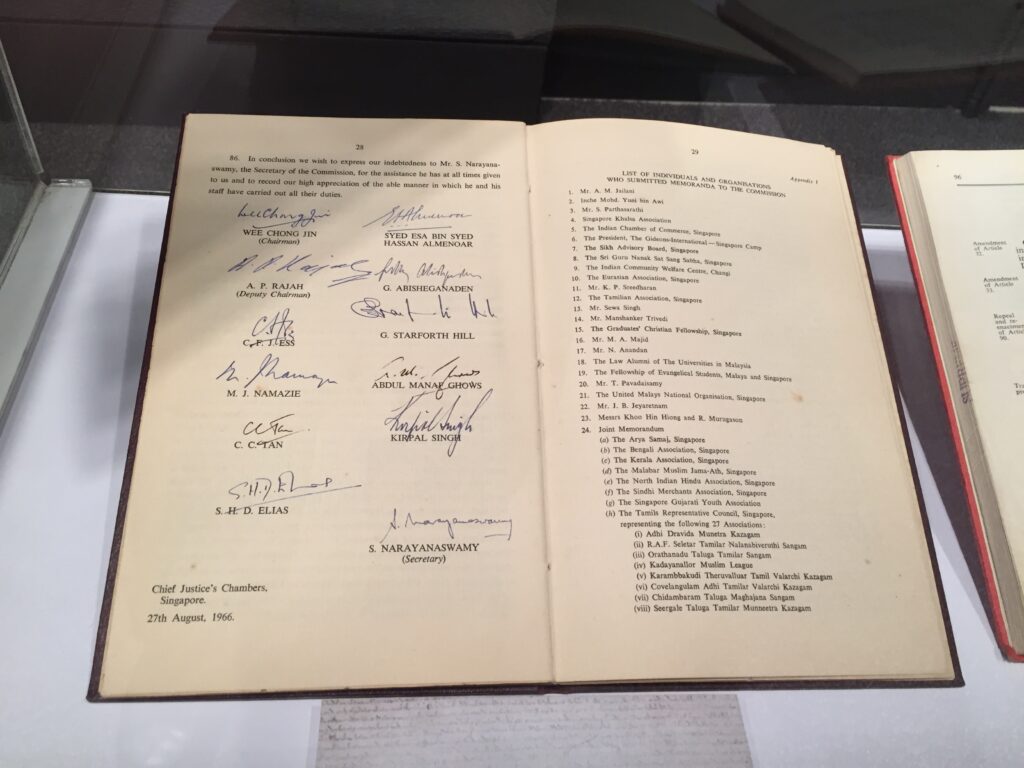

The potential of internal conflict was not the only reason why a multicultural system wasway without alternative for the emerging state of Singapore. As important were external pressures and the particular geopolitical situation of Singapore. In 1966, the Constitutional Commission mentioned in the general introduction of a landmark report:

“Whilst a multi-racial secular society is an ideal espoused by many, it is a dire necessity for our survival in the midst of turmoil and the pressures of big power conflict in an area where new nationalisms are seeking to assert themselves in the place of the old European empires in Asia. In such a setting a nation based on one race, one language and one religion, when its peoples are multi-racial, is one doomed for destruction.” (p. 1095)

While there is no doubt about Singapore’s multi-ethnic and multi-religious identity, it is not self-evident what kind of multiculturalism the Singaporean model was intended to be. Was it the idea of a peaceful coexistence of different ethnicities and religions, mediated by the state? Or was it a vision of a Singaporean identity in which all the different influences blended? While the Commission’s 1966 report spoke of a future with a “non-racial approach” because the destinies of Singaporeans were now “interwoven” (p. 1097), history moved towards the model of coexistence, or in more sociological terms, a model of “plural mono-culturalism”. (Chan and Siddique 2019, p.3).

“The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries”

History, in this case, was the politics and law of Singapore’s leadership. The system of coexistence, rather than integration, is best represented in Singapore’s CMIO model: Chinese, Malay, Indian and Other. These are the four groups that make up Singapore’s diversity and were adopted in 1959, based on British colonial practices, to manage Singapore’s ethnic policies.

Although the system is group-oriented, it is legitimised by the government as an instrument for the protection of minorities and equality at the individual level. As the defined ethnic groups are very different in size, the dominance of a numerically superior group was to be avoided through binding rules for equal coexistence. In theory, the CMIO policy should ensure that rights and opportunities at the individual level are independent of the group to which a person belongs. The practice in Singapore is more complex and beyond the scope of this blog post. However, it is an interesting case for issues of law and diversity that have been raised by Peter Collin and others, namely the relationship between equality and diversity in the law.

To this day, the CMIO model is central to administrative decisions for example on language rights in schools, public housing and other policies. While ethnicity is very often seen as a primordial category in Singapore (and elsewhere), the CMIO model is an example of interesting pragmatic choices in this regard. For it is not only the category of ‘Other’ that is obviously pragmatic, but also, and less well known, the category of ‘Indian’. Again, according to the report of the Constitutional Commission: “We have grouped Indians and Pakistanis together as one racial group for purely practical reasons.”

This example resonates well with a sociological literature that conceptualises and analyses “the making and unmaking of ethnic boundaries” as the result of “classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field”, according to which “[t]he perception of racial difference and associated practices of racial discrimination seem to shift over time and do not depend on ‘objective’ phenotypical appearance alone.” (Wimmer 2008) This is an important observation, as about 18% of marriages in Singapore are inter-ethnic, and thus an increasing number of citizens will find it difficult to identify as perceived identities gradually shift. However, Singapore’s legal and administrative rules create a system of clearly defined boxes that stabilise the system of coexistence rather than a more interwoven approach. Does the new law also move in this direction?

The Maintenance of Racial Harmony Bill

Planning for the Maintenance of Racial Harmony Bill began in 2021. The Prime Minister at the time, Lee Hsien Loong, presented two arguments as to why a new law was needed in addition to existing regulations. Contrary to what one could expect, there had been no major incidents of ethnic conflict or rioting. First, Lee wanted to emphasise ethnic equality, especially that there was no Chinese privilege in Singapore’s multi-ethnic state. An accusation that, with 75% of the population identified as Chinese, comes up from time to time. The second argument was one of anticipation, namely that with social media, the risk of ethnic provocation and conflict had increased to the point where political action was required.

The bill was passed by Parliament on 4 February 2025. It covers acts by individuals or organisations that “cause feelings of enmity, hatred, ill-will or hostility between different races in Singapore”. In such cases, “injunctions” issued by a “Presidential Council” can prohibit an actor “from addressing the general public in Singapore, either orally or in writing”. Another important element of the bill is “measures against foreign influence”, whether financial or in the form of communications. The bill was criticized (here and here) for its potential to halt free speech and dissent, for example with regard to sensitive topics such as the humanitarian situation in Gaza.

As the bill strengthens the co-existence of different ethnic groups, it could also be read as an embodiment of Singapore’s colonial past, as emphasised above. There are, however, other interpretations, such as that of Cherion George, a Hong Kong-based professor and eminent commentator on political developments in Singapore. George argued in the opposite direction, that the bill would rather provide a softer version of what was previously provided for in Singapore’s criminal law, inherited from British rule. George made two interesting points: First, the new law would make it harder, not easier, to use it as a weapon against an opponent, as was the case with the old law with its harsh sanctions. In other words, the new law made it harder to instrumentalise the charge of ethnic discrimination, which remains a very sensitive issue in Singapore. Secondly, the new law, if properly interpreted, would provide a defence in cases where the accused can show that he or she is acting in good faith, for example by using a particular language not to offend someone but to raise awareness and in fact fight racial discrimination. At first glance, both points seem specific. However, they should not be underestimated as they could mean reducing risks and barriers to make a sensitive issue more talkable in Singaporean society.

Ethnic Discrimination and Trust

Managing ethnic diversity in Singapore is an ongoing process, and the new law is just one piece of this. To understand how it is embedded in the legal landscape of Singapore, it is important to note that it has a twin, the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act 1990. The two Acts are structurally very similar. The Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act, like the new Act, aims to prevent enmity and ill-feeling between different religious groups and allows sanctions to be imposed on religious leaders and organisations that act in contravention. It has been interpreted as an instrument to strictly separate the spheres of religion, not least because of the special status of religious leaders, communities and norms. Both laws represent the idea of potential social conflict between ethnic and religious groups, which must be moderated by a strong state, rather than trust in peaceful relations between Singaporean citizens of diverse backgrounds. This is rationalised by Singapore’s leadership with a close monitoring of inter-group relations and references to cases of inter-group discrimination. At the same time, and this goes back to the beginning of this blog as well as to the current debates in Germany and the US, it is an interesting research question to what extent social institutions and legal norms reify social phenomena even in cases where they are intended to eradicate them. In the case of Singapore, to what extent will the new law promote inter-group trust rather than deepen existing fault lines? This is a question for future research that cannot be answered in this blog post. The main idea was to introduce the broader social and institutional environment in which this new law is embedded, how it could be understood as inherited from an existing system, but also where there are some “open doors” (George) that could be passed through in the process of implementation.

Cite as: Kroll, Stefan: Risk or Trust? The Legal Management of Diversity in Singapore, legalhistoryinsights.com, 21.02.2025, https://doi.org/10.17176/20250226-165937-0