The internet provides access to many digital collections of historical maps, which constitute an interesting source as yet little explored by legal historians.[1] During the early modern period, a growing number of maps was published that served various purposes and covered territories, regions and cities from all over the world in increasing detail. Some maps did not only depict the geography of a certain region or the borders of territories but were related to legal issues such as governance, jurisdiction, courts, procedure and punishment. Recent studies have demonstrated this for maps of judicial visual inspections (Augenscheinkarten) and the ‘landscape of gallows’ of the imperial city of Frankfurt.[2] Historical maps used legal symbols to mark legal spaces, jurisdictions or legal conflicts and in this way developed into a popular medium that conveyed legal images to a broader public. In the following, the use of the gibbet symbol in maps of Frankfurt and the surrounding region will be presented as an example of how maps can be analysed as sources for legal history.

From the 16th century onwards, single maps and atlases were published that depicted individual cities and towns with their surrounding area using an increasing variety of perspectives, forms of presentation and symbols. One of the new pictorial symbols that appeared was the gibbet. Even before cartography started to delineate exact political borders of territories, maps used gallows to represent the criminal jurisdiction and power of an authority. The use of the gibbet symbol in maps and various other popular media became widespread. Its slightly ambiguous meaning – representing jurisdiction and justice as well as the spectacle of capital and humiliating punishment – was recognisable to very different audiences.

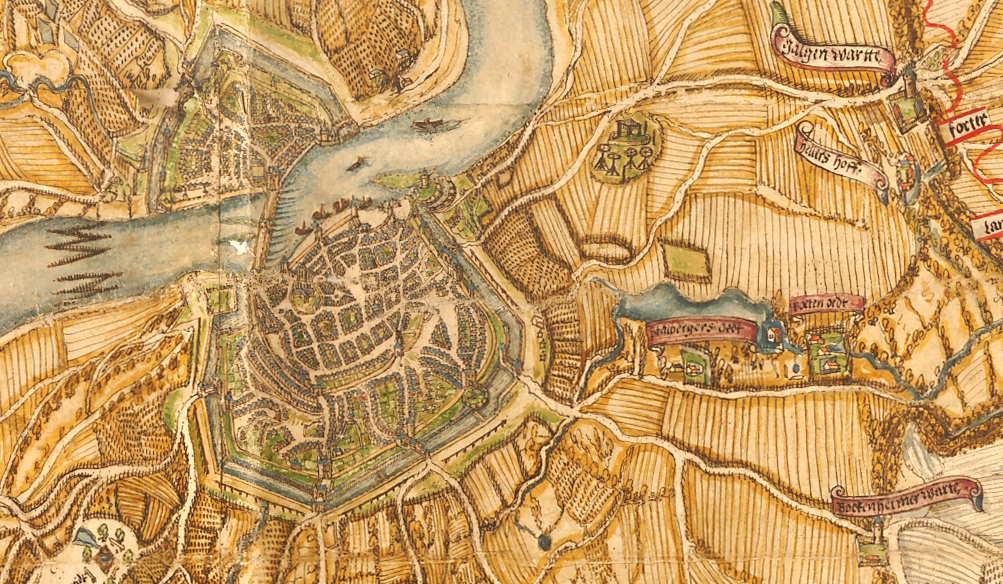

As an imperial city, Frankfurt (or rather the city council) exercised full criminal jurisdiction over its territory and had its own execution site outside the city walls to the west, near the road to Mainz. Having a permanent execution site with gallows – hanging represented one of the harshest and most humiliating punishments – was a fundamental feature of legal autonomy and sovereignty, demonstrating jurisdiction and governance to other authorities. Frankfurt was embedded in a multi-jurisdictional legal landscape.[3] Neighbouring territories, such as the Electorate of Mainz, the County of Hanau, the County of Rödelheim or the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt, also exercised criminal jurisdiction and had various court and execution sites in locations of which some nowadays lie within the Frankfurt city limits. In the 16th century, what is now the Rhine-Main Metropolitan Region and South Hesse contained about 40 court and execution sites of various authorities, none of them states in the modern sense, that is, with a monopoly of power and jurisdiction. The picture collection of the legal historian Karl Frölich (1877–1953), hosted online by the mpilhlt holds 465 images of various gallows, many of them located in Hesse.

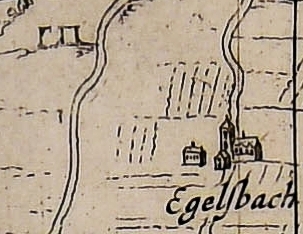

In the context of early modern jurisdictional diversity, maps gained in importance as a popular medium for representing criminal jurisdiction and legal autonomy, usually in the form of the picture of a gibbet, which was used as a map symbol from the middle of the 16th century onwards. Gallows were painted with one or two upright beams and a single cross-beam (einschläfriger Galgen) or as a triangular construction with three uprights and three cross-beams (dreischläfriger Galgen). In some cases, the symbol included hanging ropes or even dangling corpses and wheels on poles that were used to carry out the additional punishment of breaking on the wheel. Various versions of the gibbet symbol were used in several maps depicting Frankfurt and the region of South Hesse, as the following examples show:

Two gallows near Egelsbach (south of Frankfurt)

The execution site of Offenbach, the capital of the county of Isenburg, with a dangling corpse and a wheel

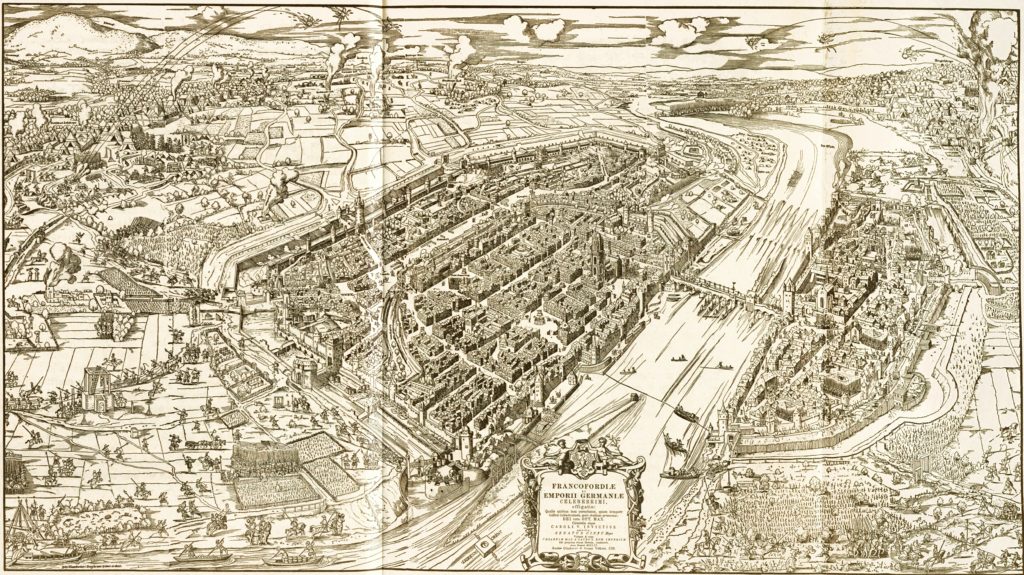

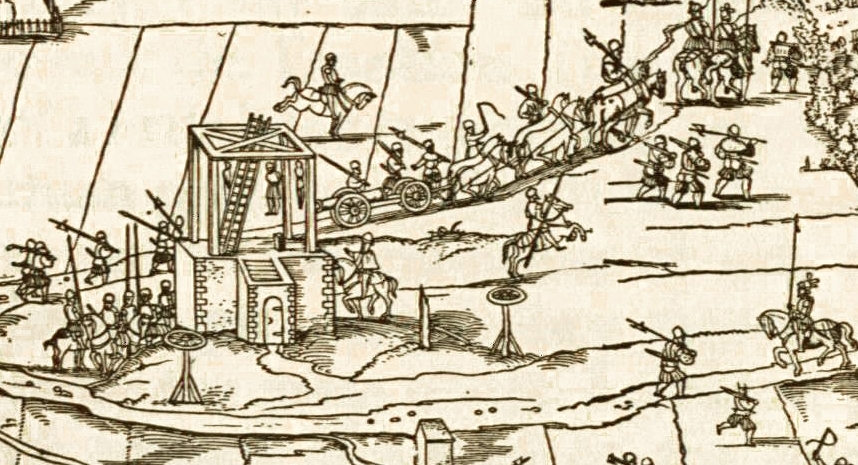

It was no coincidence that one of the first maps of Frankfurt that depicted its execution site emerged after the siege of 1552, during which Protestant princes had threatened the ‘sovereignty’ of the imperial city. The city had successfully repelled the attack, and the events were burnt deeply into its cultural memory. The name of the street where the Department ‘Historical Regimes of Normativity’ of the mpilhlt now resides, Im Trutz, commemorates Frankfurt’s successful resistance against the attack.[4] The siege is depicted in the pictorial panoramic map of Conrad Faber von Creuznach of the same year, which was commissioned by the city council of Frankfurt.

Frankfurt and its topography are shown from a south-western perspective that emphasises the city’s fortifications and various military actions outside the walls. On the left (to the west of the city), the city’s regular execution site is prominently depicted as a quadrangular gallows with six cross-beams and three dangling corpses on a brick platform that is situated on the gallows hill (Galgenberg), with two additional wheels mounted on poles, next to the Mainz road. The execution site is connected with the inner city by this road that enters the city through the gate named Galgen pfort. The prominent depiction of the gallows – drawn on a larger scale than the city itself – stresses the importance of the city’s criminal jurisdiction and serves as a pictorial representation of the ‘sovereignty’ of the imperial city.

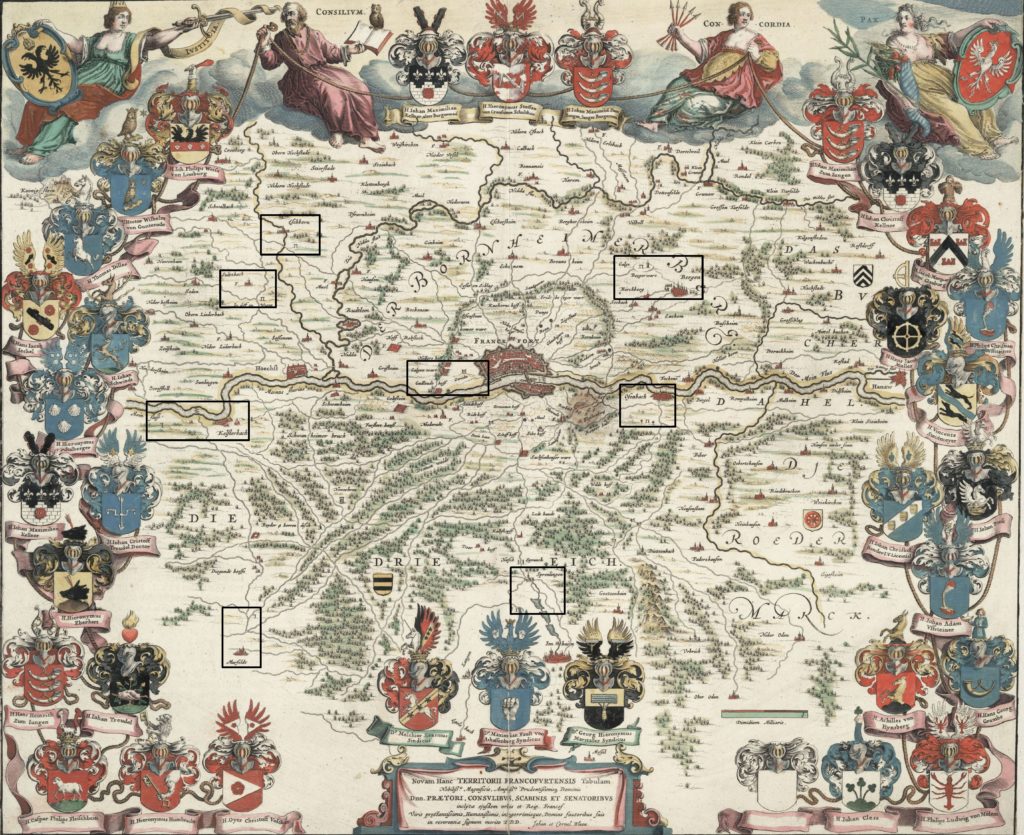

Since the turn of the 17th century, many cartographers and publishing houses in Europe issued maps of Frankfurt and the surrounding region. A famous example is the map Novam Hanc Territorii Francofurtensis Tabulam publishedby Joan and Cornelis Blaeu in Amsterdam around 1600 and reprinted in many editions (some of them coloured). The map shows eight execution sites, with the triangular gallows of Frankfurt prominently depicted near the centre of the map on the gallows hill and denoted as Gericht (court).

The other gibbet-symbols (mostly gallows with two upright beams) mark execution sites of neighbouring jurisdictions, many of them situated near borders and close to country roads.

Proceeding clockwise from the top, in the north-east of Frankfurt, near Bergen, the Bergerwart with a gallows (Galge) and a watchtower represents the district court of the county of Hanau.

In the south-east, near the town of Offenbach, a gallows and two wheels on poles, represent the district court of the town in which the counts of Isenburg-Offenbach maintained their main residence (Residenzstadt).

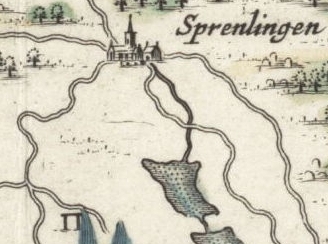

South, near Sprendlingen, a gallows with two beams, belongs to a local criminal court also located in the county of Isenburg.

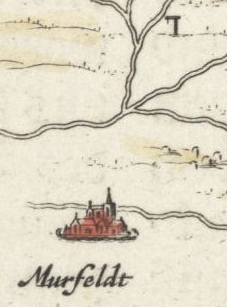

In the south-west, near Mörfelden, a gibbet with a single upright beam near a crossroads of various country roads (to Frankfurt) represents a district that became part of the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt in 1600.

In the west, near the Main and Kelsterbach, another gibbet with a single upright beam stands in a part of the district of Langen that the county of Isenburg-Ronneburg had sold to the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt around 1600.

A gallows near Sulzbach (Taunus) in the north-west, on the road to Höchst, represents a hybrid jurisdictional district shared (and contested) by the elector of Mainz and the elector of the Palatinate.

And in the north-west, near Eschborn, on the road between Schwalbach and Hausen, a gallows represents the jurisdiction of the lords of Kronberg, a fiefdom of the electorate of Mainz.

The gibbet symbols on the map chart a ‘landscape of gallows’ (Galgenlandschaft), with the imperial city of Frankfurt at its centre surrounded by various criminal jurisdictions, some of which were contested, mixed, not fully consolidated, acquired or coveted by territorial states that sought to develop their monopoly of power and jurisdiction. Hence, maps and gallows symbols can point to jurisdictional conflicts and allow us to study the visual representation of criminal jurisdiction and jurisdictional diversity. With the gallows symbol, historical maps coined a popular image of criminal jurisdiction and public punishment that is still present in modern media.

[1] See, for example: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/history/maps

https://www.davidrumsey.com/

[2] Anette Baumann et al. (eds.), Augenscheine. Karten und Pläne vor Gericht. Wetzlar 2014; Karl Härter, Galgenlandschaften: Die Visualisierung und Repräsentation von Stätten und Räumen der Strafjustiz in bildhaften Medien der Frühen Neuzeit, in: Anette Baumann et al. (eds.), Raum und Recht. Visualisierung von Rechtsansprüchen in der Vormoderne, Berlin / Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg 2020, pp. 109-137.

[3] Anja Amend et al. (eds.), Die Reichsstadt Frankfurt als Rechts- und Gerichtslandschaft im Römisch-Deutschen Reich, München 2008.

[4] See https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Im_Trutz_Frankfurt. Trutz/Trotz can be translated as defiance or resistance.

Cite as: Härter, Karl: Images of Gallows: Maps as Sources of Legal History, legalhistoryinsights.com, 19.11.2021, https://doi.org/10.17176/20211119-135651-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a