In 1847, fourteen years after escaping slavery in Kentucky (USA), William Wells Brown published an autobiography that soon became a best-seller and a landmark in the abolitionist propaganda. The epigraph of Brown’s famous Narrative brought about an existential question. Or, rather, a plea, that reflected the author’s state of mind:

Is there some chosen curse,

Some hidden thunder in the stores of heaven,

Red with uncommon wrath, to blast the man

Who gains his fortune from the blood of souls?[1]

The invocation is sublime. Brown expressed his horror at slavery as he cried out to the heavens for a lightning bolt to strike the man who “gains his fortune from the blood of souls.” His personal trajectory – a former enslaved man who had escaped bondage, acquired literacy and later became an abolitionist, playwriter and distinguished historian – portrays an era and a society: the paradoxical age of freedom in slave societies.

Brown was not alone. The autobiography of Frederick Douglass, also an American, is well-known, as is the one of Juan Francisco Manzano in Cuba. In many other societies, this literary genre flourished throughout the nineteenth century. One can even say that slave narratives are of primary importance to the literary canon in their respective countries.

Gama’s autobiography

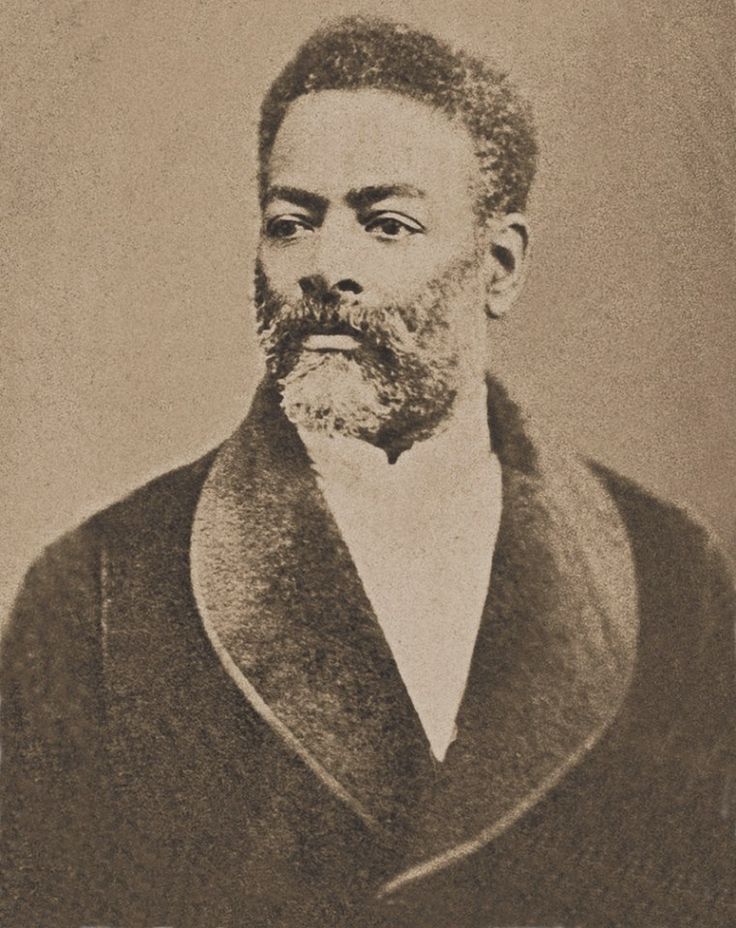

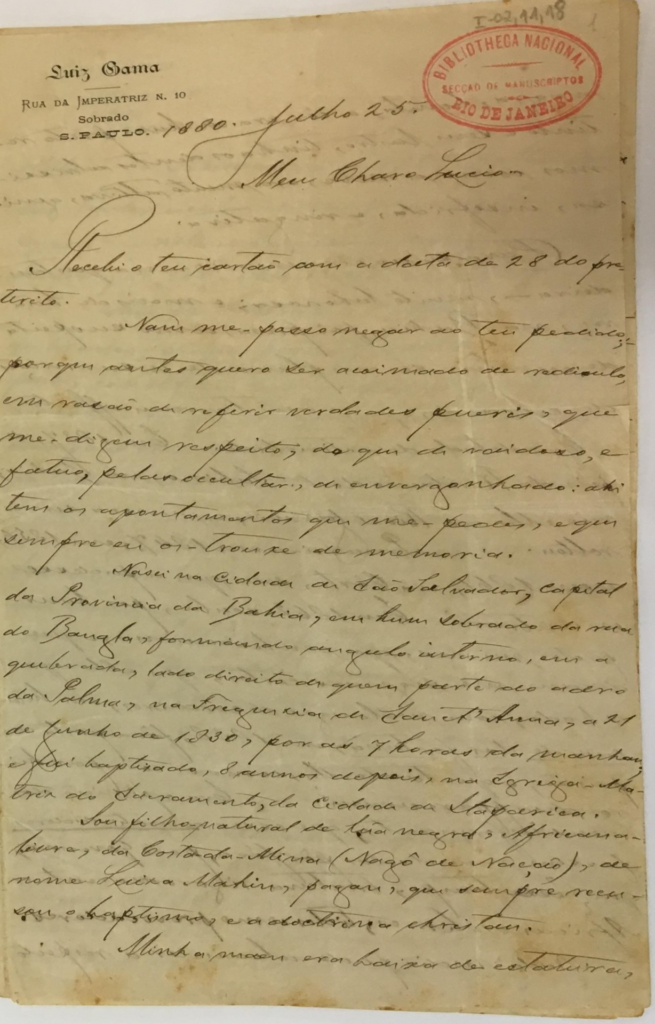

In Brazil, the most important slave narrative was written by Luiz Gonzaga Pinto da Gama (1830-1882), in July 1880. Gama was no beginner at that point: he was one of the three highest-paid lawyers in the important province of São Paulo, an outstanding economic hub and indeed the headquarters of the only law school in southern Brazil; he had authored an acclaimed book of poetry and founded several newspapers; and was widely recognized as one of the most prominent abolitionist leaders in the country.

As in Brown’s (or Douglass’) narrative, the heroic escape, the importance of literacy, the network of allies, and the triumph over adversities play a crucial role in Gama’s own autobiography.[2] However, some particularities of Gama’s own life set him apart from the other authors. First, Gama was born free and, at the age of ten, was sold into slavery by his own father. Second, he was the son of Luiza Mahin, an African woman and greengrocer who was one of the most prominent social leaders of her time. Mahin promoted both slave uprisings for freedom and republican insurrections for citizenship in the turbulent Bahia of the 1830s. In one of these insurrections, in 1837, Gama’s mother was arrested, and he never saw her again. The most reliable information he obtained, years later, was that she was deported back to Africa – a normative response commonly enforced against African insurgents.

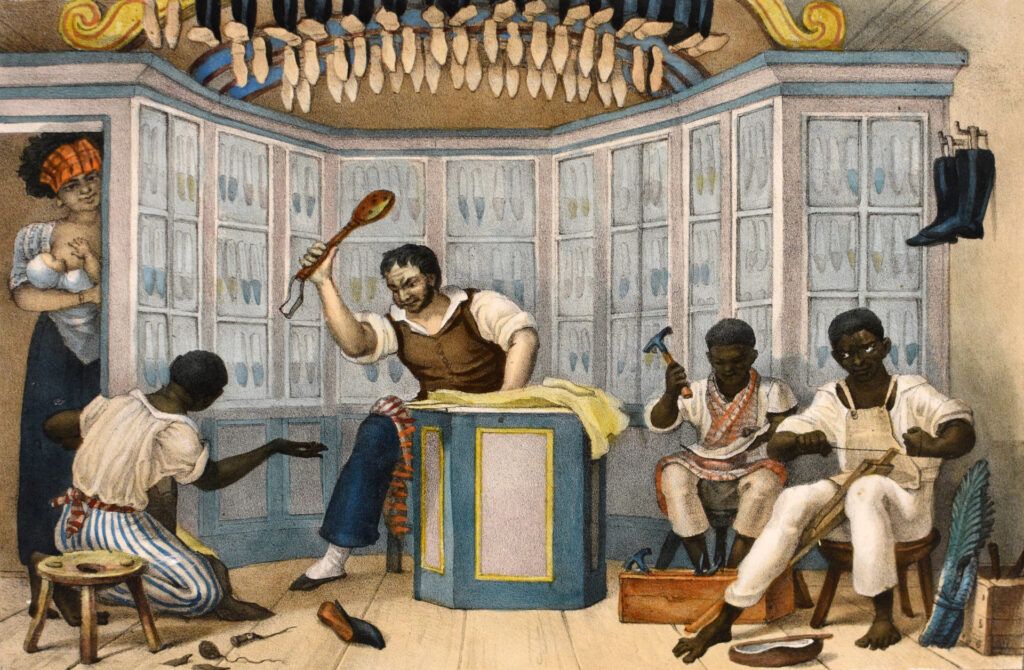

Motherless, sold into slavery, Gama crossed half the country by ship from Salvador and travelled about 300 km on foot to São Paulo. Gama spent eight long years in bondage and worked in many crafts, including shoemaking.

In 1848, an eighteen-year-old Gama was able to prove that he was a free man. We do not know precisely how he did it, but he presumably demonstrated that his purchase documents were fraudulent and vitiated – since a free person could never legally be enslaved. What we know for sure is that Gama combined two explosive elements in his escape: literacy and documents.

Gama and the law

Finally free, Gama enlisted as a soldier and, almost simultaneously, began to work in the legal world, transcribing reports, documents and records for clerks and judicial authorities. One of them, in particular, the law professor Furtado de Mendonça, befriended him, became his best man and the godfather of his only son. Furtado de Mendonça appointed Gama amanuensis of the São Paulo Police Department and opened the doors of the São Paulo Law School Library (which he directed) for Gama to put his hands on one of the greatest collections of legal literature in the country.

Disposing of legal books and the pragmatic wisdom to solve everyday problems that inevitably came knocking at the Police Office’s doors, Gama eventually mastered the Brazilian legal knowledge. Even though he was keenly interested in other fields such as poetry, politics and theatre, it was to the law that Gama devoted himself until the end of his days. Perhaps Gama saw himself as a sort of legal artist who could creatively handle the normative knowledge, especially to deal with freedom claims.

In his spare time, Gama started to shake the local courts with freedom suits. Enemies soon appeared. And they soon demanded Gama’s resignation from his position as amanuensis – which did not take long to happen. Furtado de Mendonça warned him of the serious risks of chasing freedom in a nation ruled by slave owners; yet, he washed his hands on Gama at the eleventh hour and left him to his own fate.

If Gama’s enemies were counting on his dismissal to stop him once and for all, they were frustrated. Even receiving public death threats, Gama did not stop what he called his life’s mission:

“My sole mission, a mission of which I am proud, is not to prove strength with murderers, whom I despise; it is to render aid and protection to free people who suffer illegal captivity; it is to snatch the victims from the hands of the possessors of bad faith, it is to defeat the stupid force, and the sordid cavillation, before the courts, by the law, and with the reason. My weapons are those of intelligence, in a struggle for the victory of justice, and I will stop only when the judges have done their duty.”[3]

As cleverly as he got the evidence for his freedom, Gama obtained a licence to practise law, exploiting a legal precedent that allowed non-graduates to become lawyers. He therefore became both the first former slave and one of the firsts black Brazilians to act in court.

Gama wrote his autobiography as a renowned lawyer, after winning hundreds of lawsuits and helping to free almost a thousand people. Yet, did not detail his poetic or legal work. Although in a slightly ciphered language, he gave clues, dates, events, witnesses, which, if carefully read, reveal how astonishing were his abolitionist campaigns and legal strategies. To invent freedom in the hell of Brazil, he had to do more than adapt or translate; he had to create rights through an original legal doctrine.

Towards a legal doctrine?

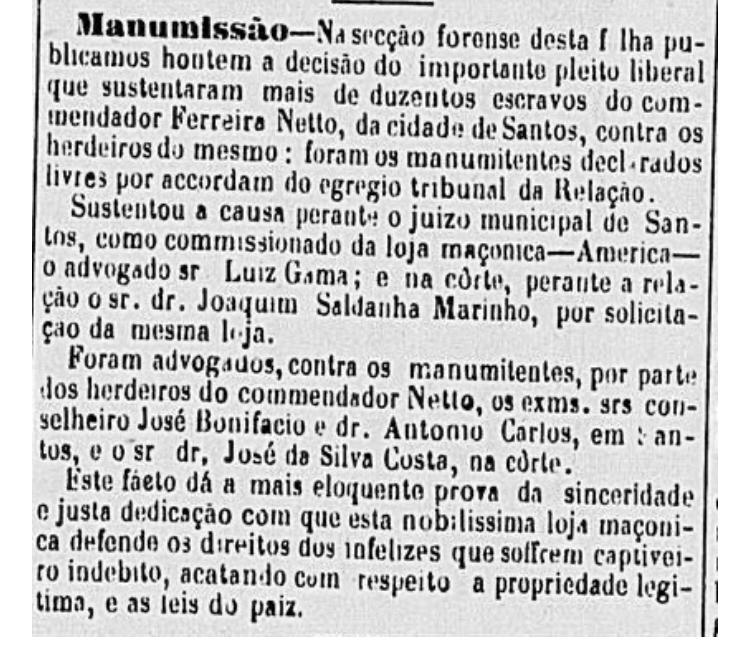

Gama used concepts of Portuguese procedural law (which were valid in Brazil). In a singular translation of the Portuguese Borges Carneiro, Gama considered the particular deposit [depósito particular] a fundamental measure for a freedom suit. Only in 1870, Gama sustained the simultaneous deposit of more than two hundred people, something never done in Lusitanian courts. And this was before the Free Womb Law, which introduced this concept in Brazilian legislation. In that particular suit, victory was achieved precisely when the judge confirmed the particular deposit. The creative use of this concept could be ground-breaking.

Gama also entered into the thorny discussion of the legal nature of manumission, whether donation or concession. This debate was consequential. In 1872, using Savigny, Gama opined that the last will of the slaveowner would be a spontaneous concession. Therefore, no possibility of re-enslavement would apply if the manumission was treated as an act of donation.

In an 1874 case, Gama creatively employed the legal principle of free soil, applying it to a ship of a nation that did not allow slavery located in international waters. In that case, Gama brought August Heffter’s modern doctrine of international law to defend the right to freedom using a peculiar notion of jurisdiction.

In 1880, Gama wrote a historical study on how the right to freedom arose from the prohibition of the slave trade. It synthesised his legal practice of the previous ten years. Gama defended that all Africans (and their descendants) introduced in Brazil at least since 1831 had been illegally captured and should be considered free by judges and deserved Brazilian citizenship. Gama knew this idea was potentially explosive: almost one million enslaved men and women could be declared free. Although he won one important case with that legal reasoning, he was defeated in many others.

Gama has developed concepts of civil procedure, inheritance, international law and on the slave-trade multinormativity, throughout a hundred processes. He always considered freedom a natural right of every human being, of every colour, equally brother to each other as sons of the one God.

Luminous like a thunder in the darkness that was Brazil, Gama seems to have come – if one may consider the plea of the enslaved who found in him the only hope of struggling for emancipation – from some of the stores of heaven.

BBC News Brazil has reported on my research. In the article, I presented an unknown lawsuit that reveals that the lawyer Luiz Gama judicially obtained the freedom of 217 enslaved people. Historians consulted by BBC News Brazil say that this archival discovery may be the biggest freedom suit both in Brazilian and Americas history, contributing to rewriting the 19th century legal history in the Atlantic World.

[1] See: Narrative of William W. Brown, a fugitive slave. Boston, 1847 (front page).

[2] Brazilian National Library, Carta a Lucio de Mendonça, Manuscript – I-2-11,018, São Paulo, 25/07/1880. The following biographical information is based on this source.

[3] In: Correio Paulistano (SP), Foro de Jundiaí (Delegacia de Polícia), 01/10/1871, p. 2; my translation.

Cite as: Lima, Bruno: “Hidden thunder”: Who Was Luiz Gama?, legalhistoryinsights.com, 23.06.2021, https://doi.org/10.17176/20210628-143639-0