Read Part 1 here

In the 16th century, knowing whether someone was a “man” or a “woman” had enormous consequences, but the possible categories relating to “sex” did not end with this binary division. Apart from medical books, there were legal texts, doctrine and consultations of the Inquisition – to mention only a few sources – that foresaw and disciplined certain sexual behavior and identified different uses of sexualities beyond the “heterosexual” relation. If someone was not using the body “properly”– as some authors of the second scholastic, such as Francisco de Vitoria, would write – the deviant act could be determining one’s life. Let me give an example.

Sodomy had been penalized in the Fuero Juzgo in the 13th century, and punishments was from them on incorporated in all the Portuguese Ordinances. In the Ordenações Filipinas, a person who engaged in a homosexual relationship could be burned in a fiery pit). Dress code laws in the same Ordenações reflected the general idea of a theoretical obedience to a binary gendered life: no man should dress as a woman, nor use “female” clothes or any mask, and no woman should do the same with “male” clothes. If anyone defied this commandment, he or she could, depending on their status and condition, be flogged publicly, or exiled to Africa or Castro-Marim, a frontier land. They also had to pay a fee to the person who accused them.

But these examples reflected only the letter of the law, and therefore not everything. Looking beyond letters and texts, daily life can show us that people’s sexual lives were not so limited, “organized” and binary. We can observe various manifestations of people’s sexual lives beyond the binary division of gender, particularly in the inquisitorial procedures. In these documents, everyday life was reported and described in detail, including accusations of homosexual acts or a specific act of “sodomy”. In order to condemn someone for such a crime, it was very important first to define which “sex” they belonged to. Looking for sodomites in every part of the Empire, the agents of the Inquisition needed to know which sex the person belonged to in order to configure the offense. However, in many situations the “sex” was not all that easy to establish, and a physical examination by doctors of the Inquisition was necessary. What is striking in this context is that they did not expect to find only men or women. Doctors could also expect to find cases of hermaphrodites and people who had undergone a sex change. Let’s take a look at the possibilities and consequences .

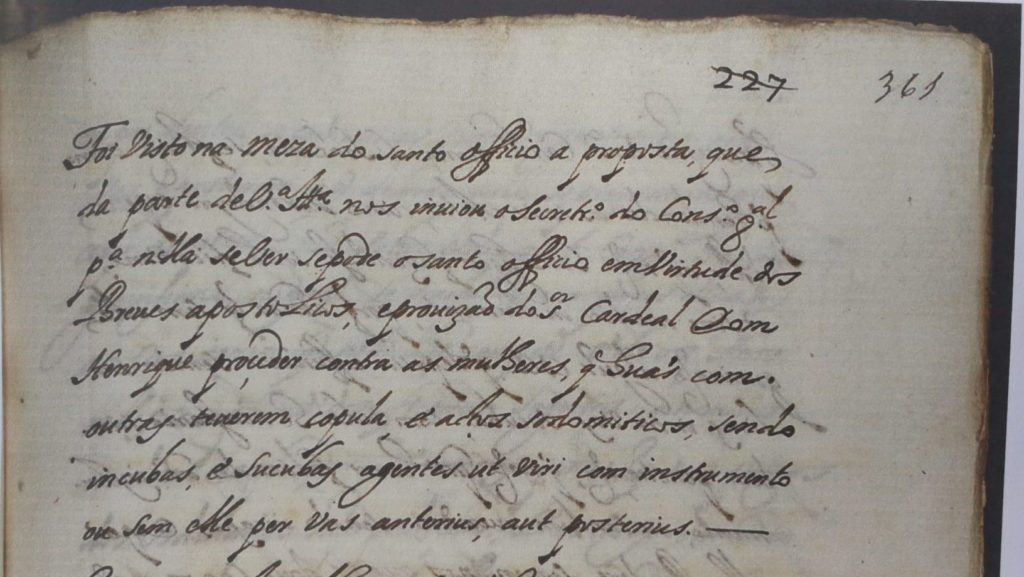

If the person was defined as a man having relations with a man, the situation was easy to configurate and condemn: a classic case of perfect sodomy, or anal sex between men. But if two women were involved, a possible case of sodomia foeminarum – if they were both considered to be women – the situation was more complicated . Female sodomy posed real(ity) problems to the agents of the king and, later, the inquisitors (the crime was only judged by the Inquisition from 1562 onwards). When two women were involved, it was very difficult to determine the exact moment of ejaculation, ie the consummation of the crime, and to determine the subsequent penalty. That is why over the years accusations against female sodomy dropped: the accusers did not know how to configure the crime. There were so many doubts about how to judge these women that in 1646 the Secretary of the General Council of the Inquisition consulted the Holy See to ask if they could proceed against women who had committed acts of sodomy with each other. The Inquisition’s counselors were of the opinion that this was a dubious matter, and not one covered by the Apostolic briefs. Therefore, the Inquisition should not issue charges in matters of female sodomy until such time as the Holy See published a new understanding. Furthermore, situations involving a man and a woman could also end up in inquisitorial investigations: imperfect sodomy could occur if a man and a woman had anal sex.

Now – in cases where the sex was not clearly established at the beginning of the procedure, during the accusations, and the inquisitors kept having doubts as to which sex the person belonged to, they had to resort to a physical medical inspection. There are many cases like this in the Torre do Tombo Archive, in Lisbon. I will mention a few examples.

António, a black man from Benin, was known for dressing as a woman and trying to seduce other men in the Ribeira area, Lisbon. After he was arrested he told the Inquisition that he had a birth hole, which was disproved by the medical examination of the Inquisition.

Manuel João, a cook at the Seminário de Viseu, was investigated and later condemned because although he was a man, he used to cook in places where only women met, worked and engaged in activities, and he performed tasks that were normally carried out by women, like sifting wheat and kneading dough.

In 1668, the Inquisition of Évora accused Estevão Luis, a free mulatto, of practising witchcraft. As it came to light in the process that he had several sexual relations with both women and men, it was suggested that he was a woman or a hermaphrodite. An inquisitorial medical examination attested his masculinity.

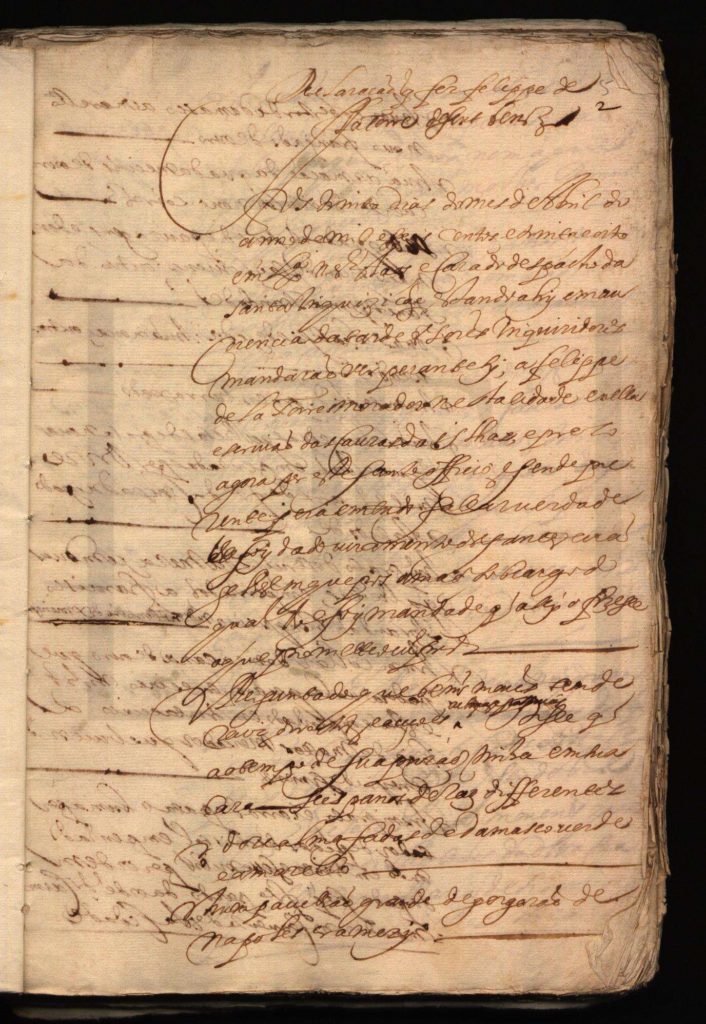

Filipe de la Torre was accused by witnesses – one of them being his own wife, Maria de Cerqueira – of dressing like a woman, in his wife’s clothes, and of having homosexual relationships. At the age of 20, he was condemned for committing sodomy and on March 11, 1640 sentenced to six years on the galleys, as well as being publicly flogged in the streets of Lisbon.

The case of Father Pedro Furtado also led to questions about his genitalia. The Inquisitors had a long and erudite discussion about how to define the situation, relying on names such as Hippocrates, Pliny and many moralists to conclude that it was metaphysically possible for “people who changed their sex” to exist – not to mention those that effect this metamorphosis by “diabolical art”. To be sure of the situation, they arrested the priest. Two doctors from the Inquisition examined the suspect and concluded that Furtado had a “virile” male member, the “vaso traseiro” was in its place and in proportion common in nature, without any sign or demonstration that he was a woman or a hermaphrodite. He was simply fanciful and astute in his strategy to find partners and satisfy his sexual fantasy. Finally, he confessed that he used a leather sling to cover up his unwanted male genitalia. In the end, he was accused of “fazer-se passer por mulher”, or making others believe he was a woman, and of lust, heresy and sodomy.

These cases show that although one could be born a woman, the “sex” was not immutable, opening the path for us to see other ideas of “becoming” and “being born with” the physical attributes of one sex or the other in the 16th century. But, particularly, these examples can help us think about how we can advance the field of women’s history, gender studies and legal history. The concept of gender cannot be guided by a binary division anymore; rather, we have to make the legal history of this period much more complex, as my examples showed for the early modernity in Portugal: people did not resort only to a simple classification of people as man and woman.

So: why use a concept such as “women” to understand legal history, if it is already being defied in the present and has proved to be so fluid in the past? I would say exactly for these critical reasons. Because we have to start with a complex, very fluid definition of what was a woman in the period under analysis – and there are more sources we can rely on – and analyze the understanding of the sexual difference in as many places as possible in order to come to a dynamic knowledge, one that is not static. The Portuguese Empire, in my case, has been an interesting example for how to connect so many different systems.

Furthermore, if I isolated the information highlighting only an aspect of the sources for a simple illustration here – people’s sexual differences and identities – it is clear that the information in such terms is incomplete. However, in contrast to the periods that followed these cases, we do not yet have the concepts of race and class, as I said before. Therefore, in my view, it is the status and condition – freedom, age, marital status, family position, social condition, religion and sexual difference – that makes the difference. For example, in Brazil it was highly relevant to ask: was she a legitimate or illegitimate daughter? Jew or catholic? Honorable or not? Rich or poor? A widow or a wife? If she was a nun, which order did she belong to, and inside the order, what position did she hold? Was she married to, or born of, a peão or fidalgo? How old was she? What was the color of her skin? Was she free?

But this is only a start.

The layers of complexity necessary to properly analyze sources vary depending on the specific tradition and the historical context under scrutiny. When we move to other places that were somehow connected to the Iberian Empires, this analysis requires completely different axes, definitions and ways of organization in order to construct a knowledge of what a “woman” was. It requires parameters that include local practices, norms, rules, principles and discourses. In colonial spaces, taking as reference the Iberian Empires, the European model and the practices revealed by other sources do not apply because, of course, they are not universal after all. Therefore, we need to open up the interpretation of “gender” and lived sexuality and re-think our classifications of the differences. We need to relativize the power of such classifications in some societies because not all societies were and are organized on the basis of gender, nor even the sexed body, or the oppositional division of gender in male and female (as Oyeronke Oyewumi has already shown so powerfully, as well as Regina Kunzel and Nan Enstad, to mention a few). Finally, we have to relativize even the “science” that created the idea of distinct sexes (in our case, biology and edicine).

That is why I am convinced that a global legal history of women in the Portuguese Empire is the key to understanding the legal history of colonial women: this shows us the way in, and once we take that step, there’s no turning back, the only way is forward. A global women’s legal history could be this step forward: taking a global perspective could show us indeed that no person is predetermined, but rather both a unique individual and a result of the collective construct of their culture. “Global” evokes differences, comparisons, connections, how identity is acquired and diverse; the cultural meaning that is given to someone when “he”/”she” is born and how such knowledge was culturally translated when moved and shared, and how the local is important in this process.

This approach can show us how a woman can be a woman: a woman is not simply born, she becomes a woman – but this can only happen in a place and time where a concept of “woman” already exists. And, of course, this is also not essential or given by nature. As there are historical variations of the meaning of “woman”, so there are for the meaning of “gender” as a system. Therefore, this could also open new paths and new conceptual approaches and frameworks in understanding the current discussion on the uses of the terms woman, man, sex, sexual, difference, body and gender, beyond the cultural political meaning tied to nationalist discourses and borders. And, of course, they are much less centered on authoritarian metaphysical discourses (of power).

Cite as: Coutinho, Luisa Stella: Becoming a woman, being born a man: going beyond binary divisionsof gender in the making of a women’s global legal history – Part 2 , legalhistoryinsights.com, 22.12.2021,https://doi.org/10.17176/20211222-164406-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a