By citing a passage from it [Henry Wheaton (1855): Elements of International Law, 6th ed.], the Chinese had compelled a Prussian warship to relinquish three Danish vessels captured on the coast near Tientsin.

William A. P. Martin, 19 July 1864 (Duus 1966, p. 25)

This excerpt from a letter to his friend, written by an American Presbyterian missionary in China, gives us a welcome departure point from which to explore what it means to practice international law. The incident to which Martin was referring was later credited as the first application of international law by China (Tsiang 1931, Wang 1990, Zou 2005, see also Lam 2024). This recognition partly arose from Wheaton’s book being utilized by the Zongli Yamen (總理衙門; Ministry of Foreign Affairs) in its dealings with the designated Prussian minister to China (欽差), Guido von Rehfues, between April and June 1864. However, there is more to this story, as the members of the Zongli Yamen relied on a translation of this normative text into Chinese, which was still in the process of being edited at the time of the incident. Thus, Martin, one of the editors of this translation, in his letter to his friend, already highlights important aspects of the general issue at hand: Who were the relevant actors involved, and what were their practices, if one seeks to gain a more detailed understanding of the incident? What does it mean to ‘cite’ Wheaton, and what precisely constituted the normativity to which Martin was referring? Was it indeed normativity derived from the ‘Elements of International Law’ and/or the ‘萬國公法’ — the title under which the text was published shortly after the incident, having seemingly demonstrated its practical utility? Moreover, in attempting to answer these questions, one must also bear in mind that the incident in which the Danish ships were captured took place in the Bohai Sea — waters off the east coast of mainland China, which the Zongli Yamen claimed as 內洋 (inner ocean) vis-à-vis Rehfues, a term seemingly not included in the translation.

This blog post sketches the story of the capture of the three Danish ships by the Prussian warship, the Gazelle. It sheds light on the broad range of actors involved and the arguably messy dynamics of their mutual engagement that eventually led to the release of the Danish ships. I will ask what it means to practice international law, and in doing so draw on the heuristic tool: knowledge of normativity. A concept employed by researchers in our department as it helps to integrate otherwise disparate analytical fragments.

Taking Prizes in the Bohai Sea

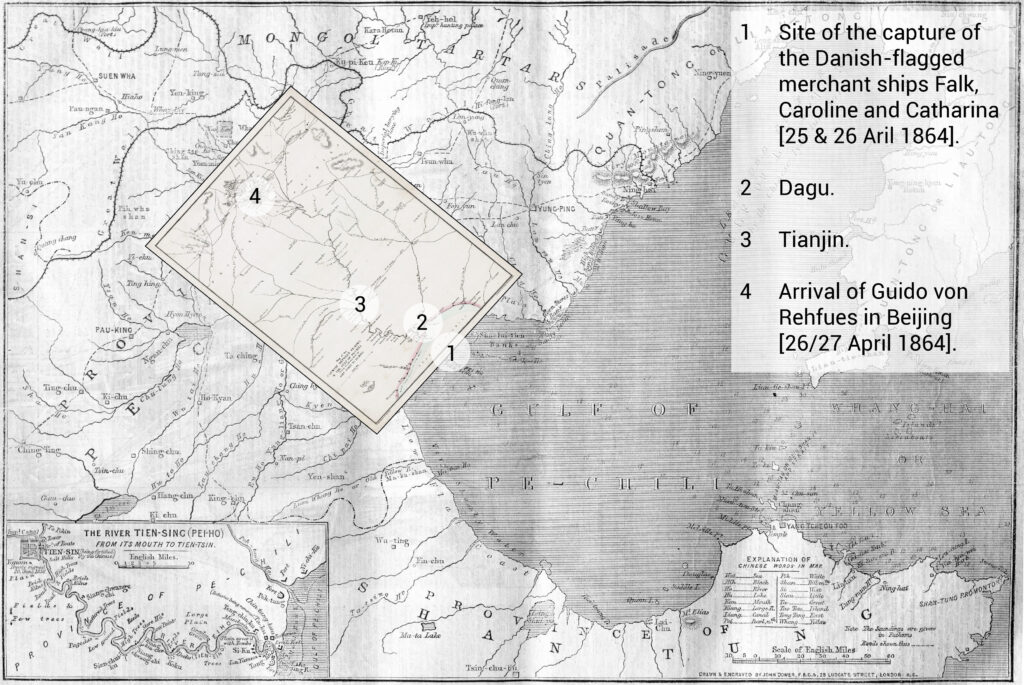

The capture of the three Danish merchant ships (Falk, Caroline, and Catharina) by the Gazelle occurred in the Bohai Sea within the context of the Second Schleswig War (1 February 1864, to 30 October 1864) between the German Confederation (Austria and Prussia) and Denmark. On 19 April, the Gazelle arrived there to bring Rehfues to the port of Dagu, from where he would travel by land to Beijing to be accredited as the Prussian minister to China. After Rehfues had already left the Gazelle, the Danish ships were spotted on 25 April and the following day, all three were taken as prizes on the command of Captain Arthur von Bothwell. Consequently, the effects of the war were not only felt in Europe but also entangled the members of the Zongli Yamen, who claimed the Bohai Sea as China’s 內洋 (inner ocean), where foreign warring parties were not allowed to engage in hostilities.

Of Travels and Translations

It was in mid-September 1863 that Martin, who had previously served in various positions under several U.S. officials in China for around ten years, was formally introduced to the de facto head Gong Yixin (恭親王奕訢) and chief minister Wenxiang (文祥) of the Zongli Yamen (Liu 2006, p. 121). The meeting came about through Anson Burlingame, the U.S. minister in Beijing, who in spring 1862 was approached by Wenxiang on a suitable text on international law for translation into Chinese. Burlingame recommended ‘Elements of International Law’ and knew that Martin – who was at this stage probably assisted by He Shimeng (何師孟), Li Dawen (李大文), Zhang Wei (張煒), and Cao Jingrong (曹景榮) – had been working on a complete translation of the book since 1862 (Han 2010). Martin relates the occasion at the Zongli Yamen in September 1863 personally: ‘The Chinese ministers expressed much pleasure when I laid on the table my unfinished version of Wheaton, though they knew but little of its nature and content.’ (Martin 1896, p. 233). The head of the Zongli Yamen, however, seems to have been more skeptical than Martin wanted to admit. Prince Gong immediately advised Martin and Burlingame that they both needed to know that ‘China had her own institutions and systems, and did not feel free to consult foreign books’ — this in an attempt to forestall any demands that China should act according to the translation in the future (IWSM, 27:25b-26a; translation by Hsü 1960, p. 132). On looking at the manuscript himself, Prince Gong found that Wheaton seemed useful but difficult to comprehend; reporting later to court:

Examining this book, I found it generally deals with alliances, rules (法) of war, and other things. Particularly it has rules (法) on the outbreak of war and the control and restrain between states. Its words and sentences are confused and disorderly; we cannot clearly understand it unless it is explained in person. We may just as well take advantage of this [Martin’s] offer and comply with his request. (IWSM, 27:26a; translation by Ku & Hsü 1960, p. 132)

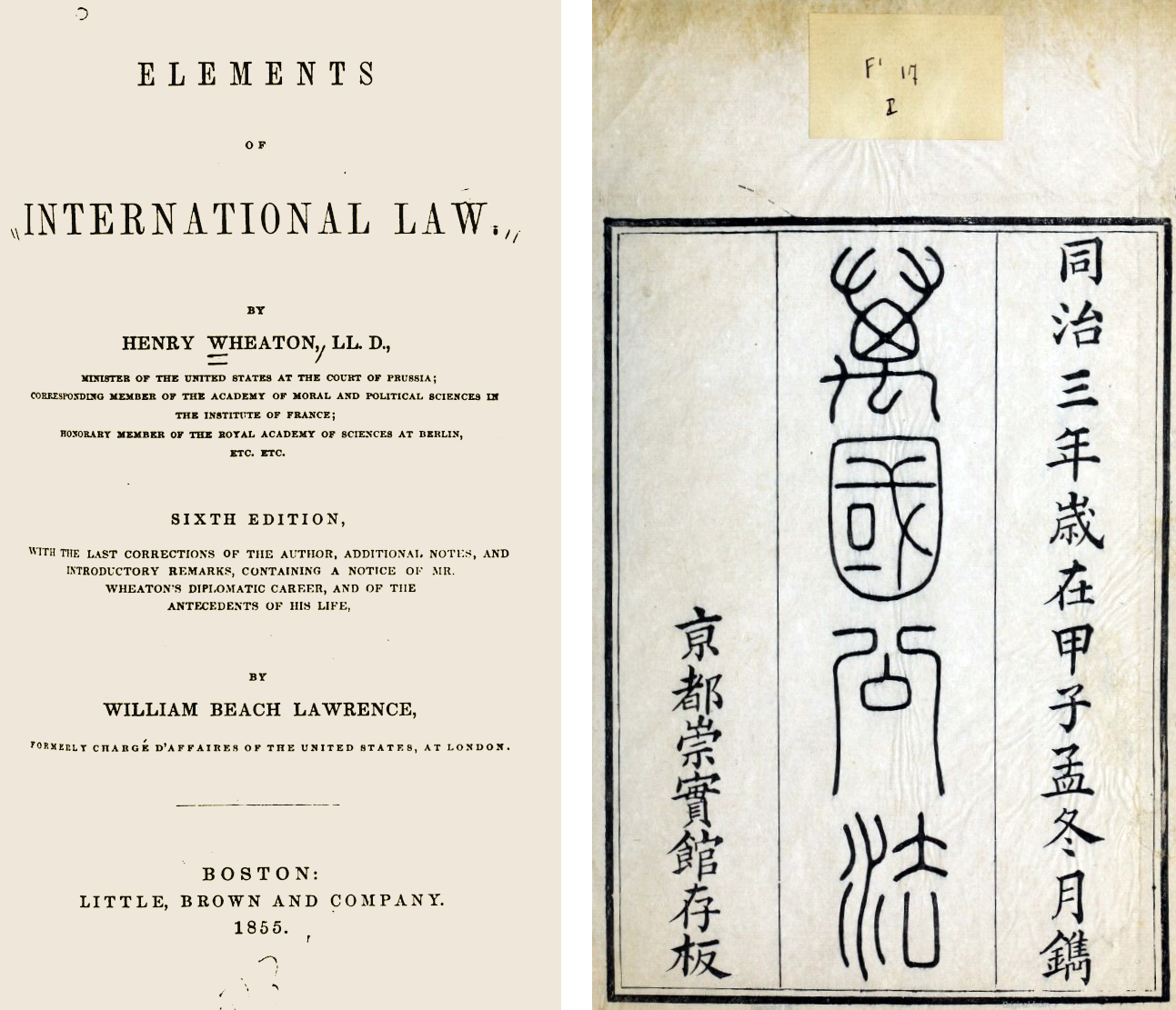

‘Elements of International Law’, published in 1855. This edition served as the basis for the translation and was the first edition to be annotated by William Beach Lawrence. © Harvard University | Right: The title page of the first edition of the Chinese text ‘萬國公法’ (1864). © The University of North Carolina at Chapel HillAbout Martin’s motivations, Prince Gong writes that ‘his intentions are, first, to boast that foreign countries have political orders (政令) also’, and that he probably wants to ‘follow men of the past like Matteo Ricci to make a name in China’ (IWSM, 27:26a; translation by Ku & Hsü 1960, p. 132). Consequently, a room was set up for Martin near the Zongli Yamen, and a special commission consisting of Chen Qin (陳欽), Li Changhua (李常華), Fang Junshi (方濬師), and Mao Hongtu (毛鴻圖) was appointed to revise the manuscript and bring it into a good literary form over the next six months (Svarverud 2007, 90).

A Chinese mare clausum?

While the book was still being edited at the Zongli Yamen, news of the captured Danish ships reached the American, British, Chinese, Danish, French, and Prussian actors in Beijing. The following excerpts illustrate the responses: one from a letter written by Rehfues to Burlingame, and the second, a memorial to the throne by Prince Gong after the incident was resolved.

As the capture of the captain of said [Danish] vessels took place according to the regular rules of war and at such a distance from those as is prescribed by international law in similar cases I [Guido von Rehfues] thought I was authorized to hope that reminding the Chinese Government of the circumstances would be sufficient to make them withdraw their declaration. This, however, has not been the case, on the contrary the Chinese Minsters maintain their declaration in protesting formally against the capture of Danish Vessels which according to them took place in an inland sea being exclusively under the control of China (Mare Clausum).

Letter of Guido von Rehfues to Anson Burlingame, 26 May 1864

We, your ministers, find that although this book on foreign codes (律例) and regulations is not basically in complete agreement with the Chinese systems, it nevertheless contains sporadic passages which are useful. For instance, in connection with Prussia’s detention of Danish ships in Tianjin harbour this year, your ministers covertly used some statements from that book of codes (律例) in arguing with him [the Prussian minister]. Thereby, the Prussian minister acknowledged his mistake and bowed his head without further contention. This seems to be proof [of its usefulness]

IWSM, 27:26a-b; translation by Ku & Wang 1990, p. 234

Taking a closer look into the exchanges, which can only be summarized at this point, the following emerges: The actors involved in the translation process of Wheaton’s book into Chinese translated the term ‘maritime territory’ with the Chinese characters of 各国所管海面, meaning ‘ocean area within the jurisdiction of a nation’ (Hsü 1960, p. 133). However, Prince Gong decided to use the term inner ocean (內洋) throughout the conversation with Rehfues (IWSM, 26:29b-35b). A term that had been applied by scholar-officials, as well as by emperors themselves since at least the Shunzhi period (1644–1661) (see Po 2018). Despite using this term, Prince Gong nevertheless applied principles described in Wheaton’s work and strengthened his claim by referencing the earlier signed ‘Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation’. He specifically pointed to the term ‘Chinese waters’ found in Article 33 of the treaty (Chinese version treaty text ‘中國洋面’/German version of the treaty text ‘Chinesische Gewässer’). Moreover, he sent Rehfues parts of the ‘Treatises on the management of military affairs’ (中樞政考), which indicated the responsibility of each military district for the control of the Bohai Sea. As Prince Gong continued to submit material to support his normative claim against Rehfues, the latter, with the help of his translator Carl von Bismarck, tried to align this information with their respective knowledge of normativity. They concluded that the Zongli Yamen was asserting a mare clausum for the Bohai Sea. Even though Rehfues could not ‘concede any value to’ the ‘Treatises on the management of military affairs’ (中樞政考), he was ultimately forced to accept the views of Zongli Yamen, which were also shared by other parties.

Through the Lenses of Knowledge of Normativity

If we take the liberty at this point to step back and reflect on the snapshot just presented, we might ask: how can it best be framed analytically? Each actor and their actions seem relevant to understanding the dynamics at play, especially when we return to the question of what it means to practice international law. The story I have outlined, which is part of my dissertation project, proves challenging to grasp using the analytical concepts commonly applied to such cases. One might consider analyzing it, for instance, through the lens of legal pluralism, the expansion of legal cultures or the process of legal globalization, in each case drawing on the idea of (legal) transplants, transfers or receptions. While each of these approaches may shed light on certain aspects of this story, each also harbors blind spots for other facets. Moreover, broad analytical concepts such as ‘legal imagination’ and ‘bricolage’ (Koskenniemi 2021) lack the accompanying terms necessary to provide sufficient clarity. However, I suggest that framing the story and the practice of international law through the heuristic tool, knowledge of normativity, helps to reveal a different perspective. What emerges is the mutual engagement of actors drawing on their respective background knowledge and engaging in the practice of translating normativity through (tactic) communication. They rely on the materiality of letters, notices, and other documents, as well as on social institutions such as personal meetings. The approach thus highlights the processes of ‘glocalization’ — the local to local (i.e. global) engagement of actors in establishing normativity with regard to a specific field of action. A form of knowledge grounded in discourses, practices, rules, and principles that constitutes, if stabilized over time, a regime of normativity – a concept that gives our department its name: Historical Regimes of Normativity.

The author wishes to extend his sincere gratitude to Haochen Ku for his invaluable assistance in the translation process.

Cite as: Pogies, Christian: Of Elements and Fragments. ‘Knowledge of Normativity’ and the Practice of International Law in the SMS Gazelle Incident, 1864, legalhistoryinsights.com, 23.10.2024, https://doi.org/10.17176/20241030-163252-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a