Time is flying by. The feeling that time is running out is increasingly present in our lives. In the blink of an eye, I have completed a year living in Germany. In what seemed like a fleeting moment, my expectations turned 180 degrees and I began to experience a life completely differently from what I imagined – in a good sense. This post is about my summer lesson almost one year ago and how important it is to allow ourselves to learn from others. Being a doctoral student in a foreign land is not easy; it is a transformative experience on a personal and professional level. I learn every day that knowledge is built not individually, but through the exchange of knowledge in the community. Looking back at my experiences in the land of Goethe, I believe that going through the Max Planck Summer Academy for Legal History was the initiating lesson. Lucky me.

And what was this lesson? After almost a year since arriving in Frankfurt, now deeper into my research and more accommodated to the daily life of this busy city, I find myself coming back again and again to what I learnt then: how legal historians deal with historical otherness.

The Summer Academy

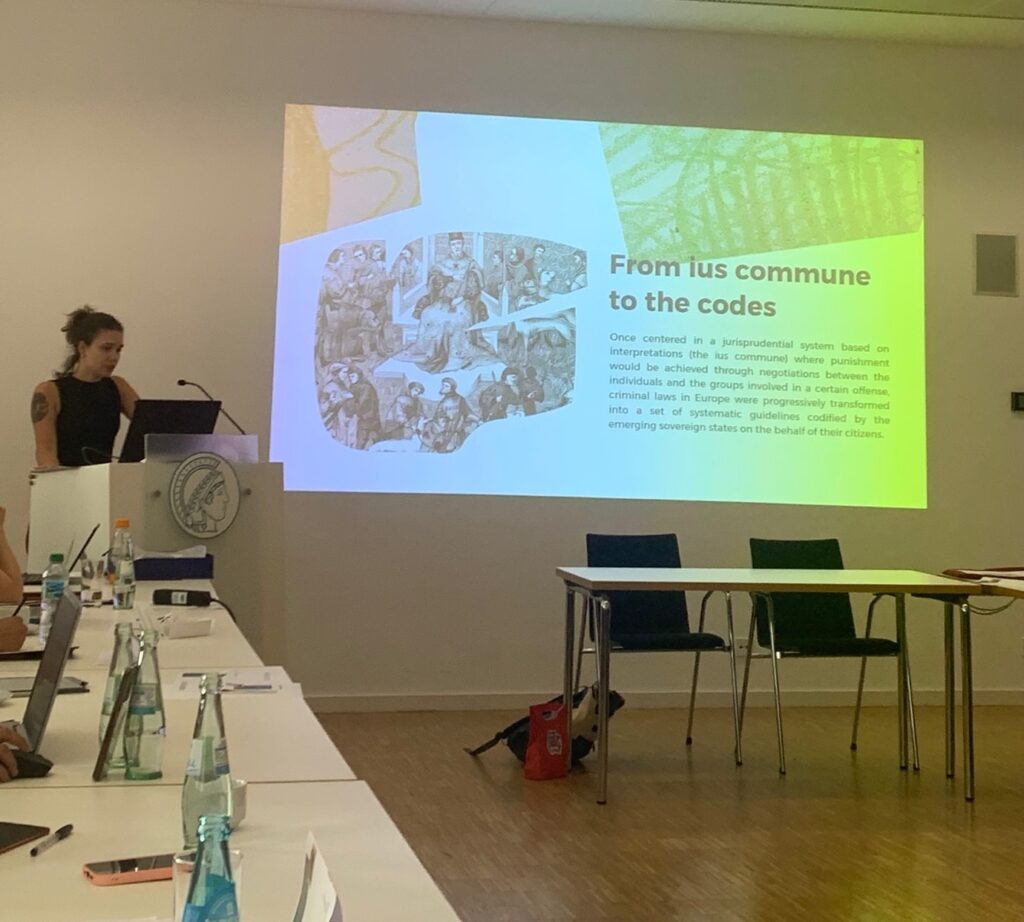

The theme for the Summer Academy 2023 was “Actors, Groups, and Identities in Legal History”. The Summer Academy is a two-week event held by the mpilhlt every year for early-stage researchers, providing introductory lectures on methods and approaches in legal history research. My participation in this event provided me with the first real footholds in navigating my new adventure as a PhD student in Germany. Bringing together seventeen graduate students with diverse backgrounds, distinct foundations, plural cultures, and, above all, heterogeneous perspectives on what legal history is, provided a unique experience: we participated not just through intensive presentations, lectures, and discussions, but we became culturally immersed in many perspectives to approach different historically constructed othernesses. I was compelled to consider diverse backgrounds and ideas, which moved me to reflect on my own knowledge, identity, and positionality in my research.

The different perspectives of analysis brought by the diverse backgrounds of the members of the Summer Academy were present in all debates, creating an enriching environment that prevented us from being entrenched in our analytical perspectives. Engaging in debates, being open to different ways of thinking about our objects, and actively listening to others were daily endeavors throughout the academic exchange.

The teaching structure was well-designed to stimulate the exchange of ideas. We not only had the opportunity to learn from renowned researchers at the Max Planck Institute about common topics in the fields of interest of legal historians, but these topics were led by the demands of critical thinking. Throughout the two weeks, we were (re)introduced to topics developed from legal history and legal theory in the three departments of the mpilhlt. The information presented in each class, combined with the diverse backgrounds of the students, sparked interesting debates that encompassed different theoretical and methodological perspectives.

Questions and lessons

For years, the field of social science, during debates about narrative, has recognized the impossibility of reproducing past events in the present. What we can do, through the application of methodological tools — often based on the collection and cross-referencing of primary and secondary sources — is re-present a historical time through narrative. We are unable to access the past as it was, nor are we able to recreate historical truth in our research. It is at this point that we recognize, as a scientific field, our limits in pursuing any “true” meaning of the human being in time and space. From this perspective, it is important to remember that the plurality of theoretical perspectives is not a problem, but rather a key to understanding the alterity that is always present in the composition of the “actors, groups, and identities” that make up the webs of a historically plural world.

This key understanding was reflected by the numerous questions addressed during the classes and project presentations that were held throughout the two weeks. The following were repeatedly present: What is the role of different social actors in the past? What are the innovations when we look at their practices? How does legal history inform the history of normative knowledge? What do legal historians contribute from their positionality and perspective? Certainly, there was no consensus on all these questions. Each of us took back to our respective homes, from Brazil to India, the concerns produced by the profound reflections embraced by the participants of the event. It is undeniable how these questions still resonate in my mind – even one year later.

And although it is one year later, I have chosen to share the experience of my first summer in Frankfurt because it is not only these questions, but also the lessons I learnt back then that still hold true: we need to think beyond our academic and institutional bubbles through dialogue; we need to be taken further by understanding that as members of plural communities, our academic work also reflects our practices, origins, and experiences. In the process of looking at the past to understand the role of actors, groups, and identities, we need to seek to answer the concerns of the present time. Between yesterday and now, we re-produce new analytical webs with each (re)encounter.

Encountering the other in my research

Perhaps my core lesson was this: I learned that it is necessary to immerse ourselves in the other. That is, we must step out of our comfort zone. It is necessary to engage with intellectual production beyond national borders. In the pursuit of this goal, it is necessary to encounter the cultures that we seek to understand by being aware of prejudices of a global north. We have to look at these actors, groups, and identities without exoticising them. We need to give voice to those who are historically excluded so that they can tell their own stories. This is why I am looking at the impacts of the one brotherhood established in Goa and Rio de Janeiro on the formation of a political culture in the Portuguese Empire during the Early Modern Era in my own research project, “From the South of the world: translating normativities in the Irmandade de Nossa Senhora da Misericórdia (Goa and Rio de Janeiro, c. 1640s – c. 1750)”.

My archival journey to Goa, a city in southern India, which aimed at collecting primary sources, fortuitously provided me with an encounter with the other. In this process, therefore, it was necessary to recall the lessons learned during the summer in Frankfurt. I learned about the territorial composition of Goa, especially its surrounding islands; the multiple layers of social organization in castes; and, among other issues, how religious traditions – from both Hinduism and Catholicism – impacted and are still present in that space. On the other hand, I was able to assist the archivists with reading documents written in my mother tongue, Portuguese. The presence of Portuguese is nonexistent on the streets, but its use was constant in the official documentation stored in the archives of Goa, since it was the official language of the area until the mid-20th century. On the streets, we hear the vibrant sound of Konkani, the local language, as well as Marathi, the official language spoken mainly in the Maharashtra region, but these are not present in historical sources. In this sense, while communication on the streets was a challenge, reading the documents was facilitated by mastering the language of the colonizer, since in Brazil, my country of origin, the genocide of indigenous peoples did not allow Brazilians to speak any language other than that of the invader, namely Portuguese.

By opening myself to new possibilities that arose from my trip to India, and to the new world emerging on my horizon, I was able to get closer to the reality of the society I chose to study. The days in the archive in direct contact with the staff expanded my horizons and made me rethink my role as a researcher. If my goal is to give voice, through my work, to the societies established in Global South during the Modern era, the days in the archive were transformative, from the encounter with those individuals who do fundamental work to safeguard and protect the documents that are precious sources for researchers, but also crucial for the preservation of local memory. Stepping into Goa, I realized the limits of my research, knowing that I will never be able to fully understand the impacts of the Portuguese invasion on those territories. Recognizing my limits as a researcher is an important step in historical research. Instead of focusing on differences and possible cultural barriers, my days in Goa were full of (re)encounters and learning. I remember here that the production of knowledge is carried out through an immersion process and, above all, through exchange between the self and others with the aim of overcoming this dichotomy to create a collective “us” that looks to the past.

The learning from the summer school in Frankfurt traveled with me to the other side of the world. For a few months last year, my first archival research trip to Goa was part of the process of immersing oneself in both present and past cultures. As a Portuguese-speaking white person, I was met with some hesitation from the archivists, almost certainly because I could read and speak the language of the colonizer. My experience in the archives caused me to consider what I had learnt from the Summer Academy when encountering the other: as legal historians, we need to learn to dialogue with both historical and present othernesses. And we must do this without trying to fit them into our standards, especially those standards we usually refer to as our “culture”. Our mission is to reflect on the construction of otherness, based on the multiple historical agents behind the societies that we seek to understand as a scientific field. Although it seems as if time is flying by, we need to take a moment to slow down, reflect, and then ask of ourselves to encounter the other time and time again. A new research trip is coming soon, in which I will again immerse myself in this other world, the world that emerges through the experience of the archive in Goa.

Cite as: Marques Marchado, Karoline, My Summer School: Learning from the Other, legalhistoryinsightsc.om, 12.07.2024, https://doi.org/10.17176/20240712-142331-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a