“One is not born, but rather becomes a woman.” This is one of the most well-known and influential sentences in the history of feminism. Written by Simone de Beauvoir in her seminal work Le Deuxième Sexe in the middle of the 20th century, it differentiated sex from gender, calling attention to the fact that gender is a fabrication not determined by nature, different from sex. The work of Beauvoir highlighted how women were considered the second sex, the one that takes into consideration the Other: women create and accept male images of themselves as their identity. The sentence both evoked and symbolized that gender is a continuous process of becoming, varying according to culture, surroundings, the Other: no woman is born a woman, but built according to a social process.

The development of the definitions of, and discussions about, sex and gender only became more and more complex after Beauvoir’s publication. The discussion on the distinction between sex and gender, whether academic or in real-life activism, continues to be prolific until today. Beyond the concepts developed by French existentialist thinkers, the terms sexuality, sexual differences, sexual identity, embodiment, bodily behaviors and biology, performative and queer are just some of the words and concepts that brought complexity to the discussion, making the field of women’s history and gender studies a rich space in which to criticize and defy the idea that “biology is destiny”. Equally important was the introduction of the intersectional approach to this field, particularly highlighted and developed after Beauvoir’s affirmation in the context of the critique made by second-wave feminists, which showed the importance of “making” the field of women’s history taking in consideration the intersection of, among others, race, class and gender.

Although this complex discussion has already thrown into question the use of “women” as a category of analysis in history, feeding a lively debate, I keep using that same word in my work. This is based on my own approach to looking at the legal history of women in the Portuguese Empire, which I developed for my recent book about women in colonial Brazil. Although I have been writing and building my own methodology to work with women in colonial contexts through the lenses of a specific understanding provided by legal history, I must confess that I have been struggling for a long time with the use of the category “women” in the context of making legal history. I sometimes feel that I have the tools to deconstruct the whole building of my thoughts – because gender solely understood as a binary division, male and female, and as a system, is in itself a construction that needs to be seen in context. Better said, a world of two sexes, a gendered world, is an invention, a fabrication, an illusion to deceive our “reality”. I am not alone in saying this. The lively debate I mentioned before both triggered and legitimizes this line of questioning, whether it is based on the arguments of performativity or even on throwing into doubt the return of the importance of male roles in historical studies, for example. In my particular case, the unease came also from “my” 16th and 17th century sources.

I ask myself every day how I can keep using such terminology in the midst of so much criticism and as I move my research to a broader analysis, which encompasses Asian territories that were formerly connected to the Iberian Empires in one way or another. In such a global view of the world, the idea represented by the word “woman” in one culture cannot simply be transposed to another, given that the category “woman” is flexible and has various meanings and connotations in different cultures – not to mention the problem of translating these terms.

Therefore, I found it useful, as I write about women and attempt to understand the past using legal history methods based on various normativities, to depart from their own definition of the term in the 16th and 17th century. To do so, I rely on different sources such as normative literature, medical treaties, laws, doctrines, and, foremost, practices found in different documents from different archives all around the world. Not surprisingly, I showed that we cannot define the concept of “woman” with any real precision – because, as we have been arguing for ages, it is fluid and never exists in a vacuum. However, instead of intersectional approaches using terms that were not known as such in the time “my” sources originated, such as race and class, I identified other axes of interpretation: status and condition, religion and spiritual practices, and sexualities or sexual difference – a perspective recently published by the Max Planck Society with various examples from sources found in archives in Brazil and Portugal. Beyond the countless and sometimes contradictory definitions and understandings of what a woman was, my work showed how practical life situations went far beyond the binary division of gender in the past. The sources and the cases I worked with shed light on how people’s sexual lives should not be exclusively defined in terms of conventional (anachronic) male-female definitions: across the globe, people acted in ways that they were not supposed to, according to stereotypical social definitions or a binary division of gender.

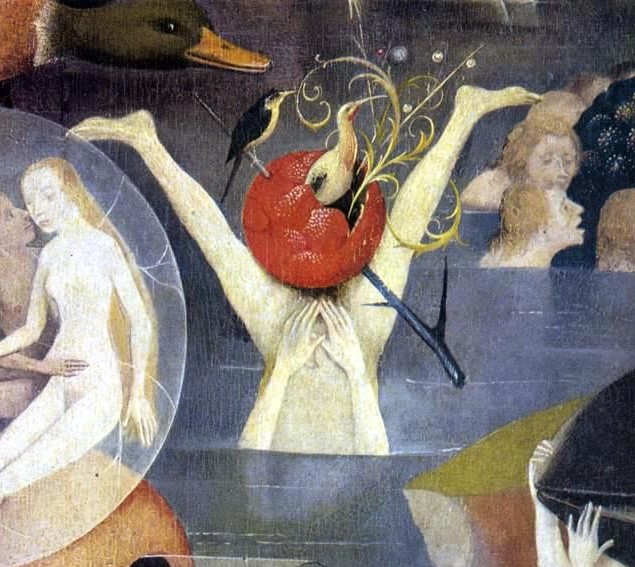

Thus, taking Beauvoir’s “becoming” as a starting point, I will explore another idea of becoming a woman or a man, one widespread in the 16th-century Portuguese Empire (as only one of the possible axes of interpretation I proposed before): that a woman could become a man, and a man could become a woman; and that people could be born with genitalia of both sexes. In doing so, I want to highlight how sexualities were fluid and how “woman” is not a narrow category in the past, but we have many definitions and combinations for it.

Let’s begin, to pick just one, with Isaac Cardoso, a Jewish physician born in the north of Portugal, probably in 1603. In book six of his De Philosophia Libera in Septem Libros Distributa, he wrote about fetuses, the female contribution to gestation, the generation of male and female, hermaphrodites and sex change. There is a question (number 14) that discusses cases of sex change, and question 15 deals with hermaphroditism. He argued that women could become men, but men could not become women. How this transformation was supposed to happen was an unknown process, hidden by nature and uncertain. As for the hermaphrodites, Cardoso wrote, they were people with the genitalia of both sexes, although one would always prevail.

But Cardoso was not the only one to defend such ideas. Amatus Lusitanus, or João Rodrigues de Castello Branco, a Jewish Portuguese doctor born in Lisbon in 1511 and educated in Salamanca, mentioned cases of ambiguous genitalia, sex change and hermaphroditism. He acknowledged the possibility of sex change and hermaphroditism based on the model of improvement of the species, a movement from femininity to masculinity as an advancement of mankind. One of the examples he mentions is particularly interesting: the case of a young girl named Maria Pacheca, who became a young man (varão) . She lived close to Coimbra, in Esqueira, and at the age of women’s first menstruation she began to develop a penis. In this way, she changed from being a woman to being a man, began to wear a man’s suit and was baptized with the name of Manuel. He went to India, became famous and rich and, when he came back to Portugal, married. However, Lusitano did not know if Manuel had a son – a topic always discussed in the context of hermaphroditism and sex change. Similarly, Estevão Rodrigues de Castro, another Jewish doctor, born in Lisbon in 1559, thought that it was only possible to change sex from woman to man; the genitalia hidden inside the woman could grow with heat, but the opposite was impossible.

If these medical treatises considered possibilities beyond those of being a man or a woman, they explained the process as unknown, hidden by nature, stimulated by heat, or, simply, by the improvement of the species.

But, in the 16th century, how could this affect people’s everyday life ? And why does all this matter to us, legal historians?

… read Part 2 here.

Cite as: Coutinho, Luisa Stella: Becoming a woman, being born a man: going beyond binary divisionsof gender in the making of a women’s global legal history – Part 1 , legalhistoryinsights.com, 10.12.2021, https://doi.org/10.17176/20211210-173802-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a