A brief itinerary of a young legal historian

Sociedade de Geografia

From Mouraria, I could easily walk to the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa by foot, or take the subway line straight to Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal and Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo.

While their early modern archival holdings may not be as abundant as other libraries and collections in Lisbon, they have a few hidden treasures along with a very good map collection, and the building itself should not be left unremarked. It is a 19th-century building that embodies the spirit of its time. The entrance stages a perfect marriage between the constitutional monarchies and the professionalization of sciences for colonial purposes. During the 1850s a number of Portuguese colonial organizations underwent a restructuring process to account for shifting imperial dynamics and the new focus on domains in Africa and Asia. This process also included the reinstatement of the Conselho Ultramarino and the state-sponsored Colégio das Missões Ultramarinas.

The Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa was conceived in this context to assist the Ministry of Naval and Colonial Affairs by compiling and systematizing geographic, ethnographic, archaeological and anthropological knowledge of overseas provinces.[1] As a result, the society houses a collection of material artifacts in its museum which can be visited on specific days or by appointment.

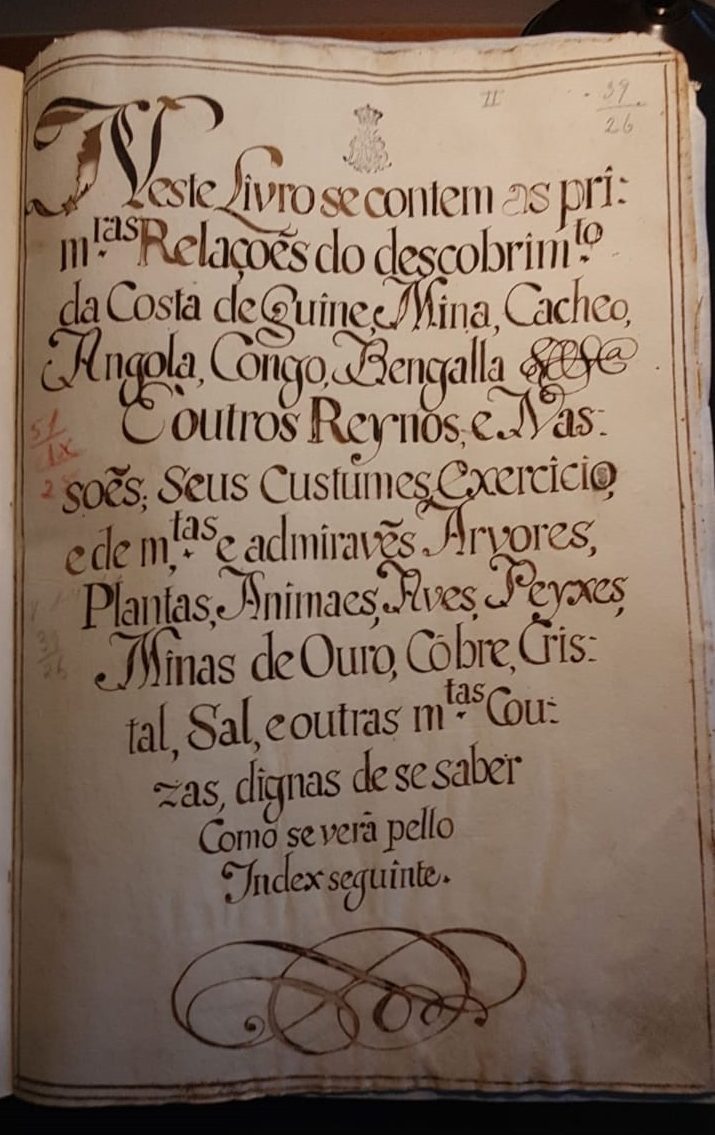

It is a mandatory visit for any researcher interested in colonialism and the history of knowledge in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, the library also contains a few precious sources from previous centuries. Besides the broad cartographic collection, there is, for instance, the unique copy of manuscript Etiópia Menor e Descripção Geographica da Província de Serra Leoa (original c. 1615, copy from 18th century) by Manuel Álvares, a Jesuit based in Sierra Leone and reporting on the larger region of the Upper Guinea Coast. It also counts among its holdings the Relações annuais of a contemporary of Álvares, Jesuit Fernão Guerreiro, regarding the diverse missionary projects of the religious order from Japan, China and Cataio, to Angola, Sierra Leone, Cabo Verde and Brazil (print originals in Portuguese and Spanish, and a modernized edition is digitally available in Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa).

The experiences of Jesuit encounters around the world were synthesized in this 17th-century three-volume publication. I was struck by reports about a mission where they allegedly had a close encounter on their way to Luanda with Dutch privateers (although they did successfully arrive in 1605-06) and the well-known failed attempt of fathers Francisco Pinto and Luiz Figueira to establish a mission in Maranhão in 1607. Through these two sources it is possible to discern, even with the thick rhetorical conventions of the religious order, a local rite of passage in one of the islands of Cabo Verde (described as “idolatry”),[2] as well as other normative descriptions on, for instance, the condemned iconoclasm of the Dutch corsairs, rituals of arrival, and the strategic attempts to establish alliances with indigenous groups and their failure.

Biblioteca da Ajuda

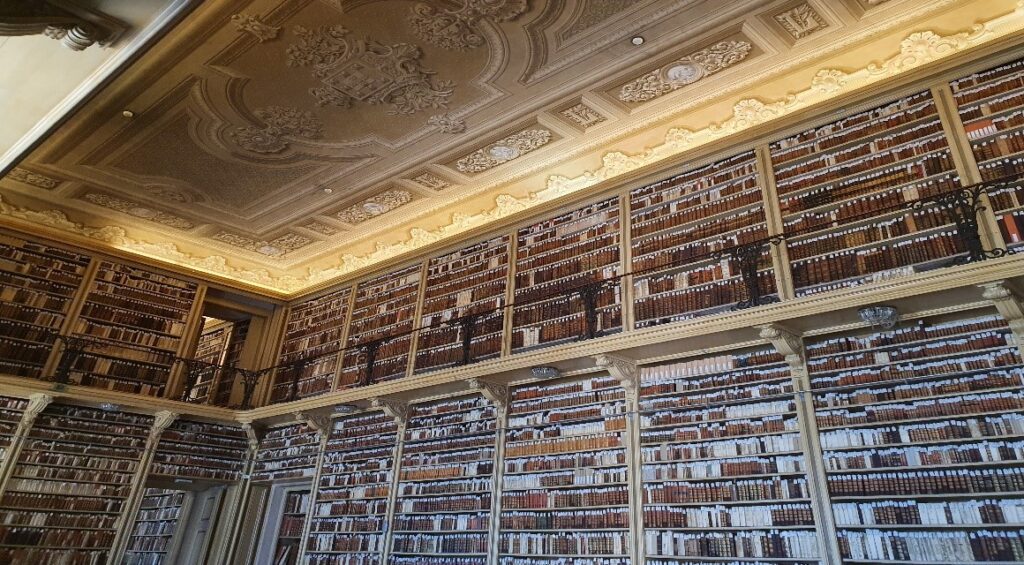

On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays I worked in the Biblioteca Nacional da Ajuda.

The Biblioteca da Ajuda islocated at the old Paço da Ajuda, overlooking the neighbourhood of Belém, where the Exposição do Mundo Português was staged in the 1940’s, a nationalist cultural event of the Estado Novo to paint its colonial empire power in a beneficial light. The Padrão dos Descobrimentos, a monument visible from the curve on the slope of arrival at Palácio da Ajuda, demarcates an architectural complex that has historically been used to represent the link between Portuguese national identity and its colonial past – the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, Torre de Belém and Praça do Império. The Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, for example, is a strange pantheon of religious features that houses the remains of Fernando Pessoa and Luís de Camões who, together with the tower, perform the Iberian architectural authenticity, without great references to the Mudéjar elements. It was from the Praia do Restelo that first Portuguese explorers like Vasco da Gama and Pedro Álvares Cabral set sail towards the Indies. We can discern in this public performance of empire traces of the regime of diversity manifested as the soft power of the Estado Novo.

This was my second research visit to the library. Previously, I had been looking for records about informal treaties, alliances with and responses to the Dutch invasion of the coast of Brazil during the 17th century. The book “Inventário dos Manuscritos da Biblioteca da Ajuda Referentes à America do Sul” by Carlos Alberto Ferreira, was a great help.[3] Unlike other archives in Lisbon, the Biblioteca da Ajuda does not make reproductions of digital copies available. Moreover, access to materials is often difficult if documents requested are deemed to be in a poor condition, which can be a major obstacle to research. Nevertheless, those needs are met by the help of the management and archive staff, who promptly respond to the emails of the reservations and selections made by researchers. I was searching for documents from the period of the Iberian Union concerning ecclesiastical and juridical-political administration in Congo and Angola during the 17th century. The documents consulted were found in the following codices Miscelâneas históricas and Governos and so called Documentos Avulsos. My primary reference for these were the published transcriptions of the Fernão de Sousa collections by Beatrix Heintze and Maria Adélia de Carvalho Mendes (1988).[4]

In the library, instead of going straight to the codices and single documents, it is recommended to have a look at the analogical reference system that the archive professionals have created, specially thanks to the work of Maria da Conceição de Carvalho Geada, a former librarian of Biblioteca da Ajuda. This in-house catalog is available only locally and it is a helpful tool for anyone who is searching for specific content in the archive. It is contained in several boxes and bound volumes situated on a piece of furniture inside the Reading Room.

Contrary to the triumphalism propagated by the Estado Novo during much of the 20th century, the 17th-century historical records in the Biblioteca da Ajuda show a different story. It is one strongly associated with other European powers, susceptible to several social asymmetries and full of internal corporative disputes. We see this particularly in the case of the turbulent government of Fernão Sousa, in charge of the colonial administration of Angola under the Iberian crown between 1624 and 1630. Maritime surveillance against English and Dutch corsairs was the subject of secret letters between King Philip III and the governor of Angola, who in a short time also had to contend with possible problems of reinóis coming into conflict with local groups and the sobas. He also had to handle insurgencies of captains in charge of the fortresses of Muxima, Massangano, Cambambe and Ambaca, located in the countryside along the Kwanza river, territories that proved to be an important conflict zone for Portuguese dominance later, during the brief Dutch rule in Luanda.

Another Lisbon Story

The governance of difference was less of an imperial imposition and more of a great network of negotiations. In the midst of this complex network, social asymmetries were built.

Some of Lisbon’s historical monuments project a mistaken image of the history of conquests, but this false projection is also part of past and present regimes of diversity. If scholars are not aware of it, they are at risk to reproduce pieces or the entire puzzle over again.

The content of the archives represents all this complexity, which juxtaposes with the city. It is the commitment of many scholars today, including legal historians, to reconstruct a more detailed view of the overseas Portuguese-Iberian influence playing less a legitimation by reversal of revivalist and millenialistic stories. In many ways, a history, perhaps more global, has yet to be explained.

[1] See in Paquette 2013, 347-71. Paquette, Gabriel. Imperial Portugal in the age of Atlantic revolutions: the Luso-Brazilian world, c. 1770–1850. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

[2] Horta 2014, 37-9. Horta, J. S. (2014). “Trânsito de africanos: circulação de pessoas, de saberes e experiências religiosas entre os Rios de Guiné e o arquipélago de Cabo Verde (séculos XV-XVII).” Anos 90, 21(40), 23-49.

[3] Ferreira, Carlos Alberto. Inventário dos manuscritos da Biblioteca da Ajuda referentes à América do Sul. Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, 1946.

[4] Heintze, Beatrix. Frontes para a História de Angola do século XVII. 1-2, Stuttgart: Steiner-Verlag-Wiesbaden-GmbH. Vols. I (1985) and II (1988).

Cite as: Guerra Pedrosa, Gilberto: Archives in Lisbon, Lisbon as archive – Part 2, legalhistoryinsights.com, 04.11.2021, https://doi.org/10.17176/20211105-162049-0

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a